Welcome, and thanks for diving into this White Paper with me!

In it, we share our take on Incentive Plans; what works, what doesn’t, and what we’ve learned from years of helping startups and scaleups design and implement tailored solutions.

Personally, I find Incentive Plan projects some of the most rewarding work we do. No two plans are alike, and when you get it right, the payoff is real: motivated teams, aligned goals, and companies that perform.

As venture culture matures, so does the mindset around equity. Sharing the pie is no longer a sign of cash distress weakness or hippy idealism but a strategic move. Shared capitalism helps attract talent, retain key people, and hit ambitious targets.

But here’s the catch: there’s no one-size-fits-all playbook and just figuring out where to start can be the biggest hurdle.

That’s why we wrote this. To give you a bird’s-eye view of the options, the data behind why they work, and the practical lessons we’ve picked up along the way. We hope it earns a spot in your toolkit. And if you think we’re the right partner to help shape your Incentive Plan, we’d love to hear from you!

Bas Jorissen

Author of this white paper👌

CHAPTER 1: ECONOMIC THEORY

Why Incentives Plans work.

When Done Right.

FIRST OFF: WHAT IS AN ‘INCENTIVE PLAN’?

Strictly speaking, anything can constitute an incentive plan really. For instance, when we speak with HR professionals, we often have to go through the motions of acknowledging that a massively positive performance review could incentivize teams, as could gym memberships or a foosball table. However, we like to narrow it down and stick the financial form of incentives – variable remunerations, in cash or equity. A definition as we see it:

WE ARE HARD-WIRED FOR POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT.

Ultimately, Incentive Plans revolve around positive reinforcement. Sure, not meeting targets and therefore missing out on an upside potential is not a positive clicker but ultimately, Incentive Plans revolve around establishing a positive relationship between meeting a target and making financial gains.

If we entertain the humorous idea that money is to man what cookies are to dogs, it is easy to see a parallel between dog science and what makes us humans tick in this Nature piece on training methods, and why cookies work and why mixing cookies up works even better. An Incentive Plan, as a financial remuneration mechanism, is a cookie. And adding an Incentive Plan to fixed pay already in place, adds to the cookie mix.

AN INCENTIVE PLAN ADDS POSITIVE FINANCIAL REINFORCEMENT.

The Incentive Plan adds an interesting upside and can help create a better mix of short-term and long-term incentives, for instance by adding exposure to company profitability and/or value.

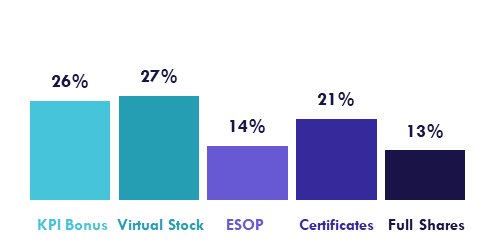

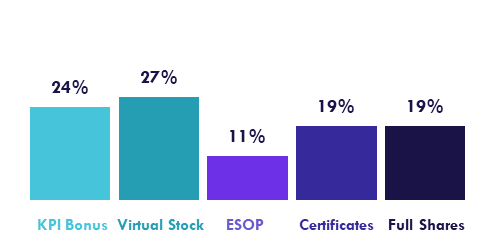

We discern 5 main ‘Main Types’ of such Incentive Plans:

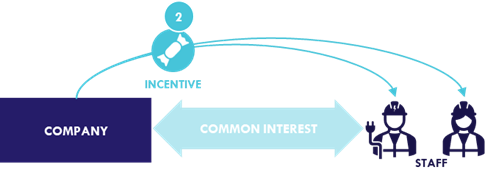

THREE REASONS FOR EIPS

1. THE PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY

The principal-agent theory explores the relationship between a principal (e.g., a shareholder or a founder) and an agent (e.g., an employee or executive) who is tasked with acting on the principal’s behalf.

The core issue is misaligned incentives: agents may not always act in the best interest of the principal, especially when their compensation is not directly tied to the company’s performance. For instance: think of executive pay vs. dividend or individual KPIs vs. company value.

Employees make daily decisions that impact company value, but without ownership they may lack the motivation to optimize for long-term outcomes. Participation mechanisms create incentive alignment by linking employee rewards to company success. This alignment encourages behaviors like long-term thinking, risk-taking, and innovation.

2. HUMAN CAPITAL AS A CO-INVESTOR

In early-stage companies, capital is scarce, but talent is critical. Employees often accept below-market salaries in exchange for the opportunity to contribute to something meaningful and potentially lucrative.

Equity or equity-like instruments turn employees into co-investors in the company’s future. Instead of being just wage earners, they become stakeholders in value creation. This fosters a sense of ownership, accountability, and loyalty.

Participation reduces the need for high cash compensation, lowering the cash burn rate. It increases talent stickiness, especially in the volatile early phases of growth. It also aligns with the startup ethos of shared risk and shared reward:

3. IMPACT ON PRODUCTIVITY, RETENTION, AND INNOVATION

A growing body of research shows that employee participation has measurable positive effects on company performance:

Employees with a stake in the outcome are more engaged, proactive, and committed.

Vesting schedules and long-term incentives reduce team churn rates and increase stability.

Ownership fosters psychological safety and encourages employees to take initiative and propose bold ideas.

The participation must be meaningful; symbolic equity has little effect. There must be transparency about the value and mechanics of the plan. The company culture should support collaboration and shared success, not just top-down control.

INCENTIVE PLANS CAN BOOST OWNERSHIP AND INCREASE THROTTLE FEEL BETWEEN EFFORT PUT IN AND BENEFITS BUILT UP.

This should add to the sense of impact and autonomy, making careers more inspired:

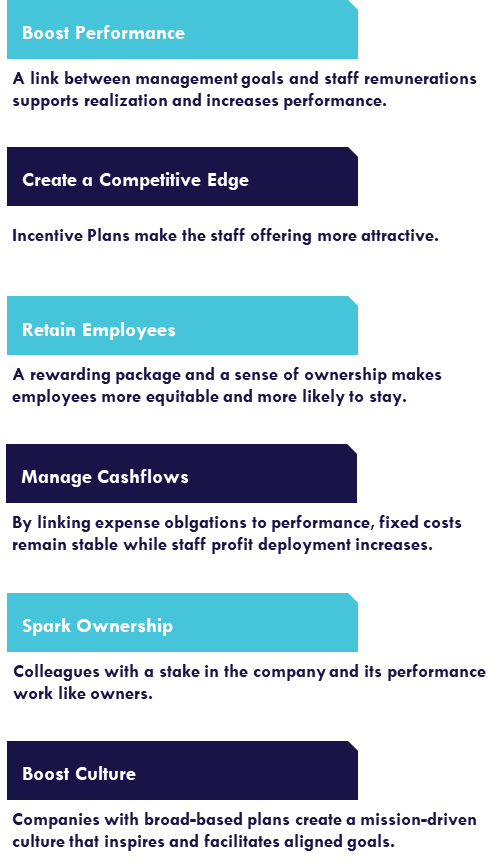

On a Company Level, Incentive Plans can help:

According to assorted studies published in the Harvard Business review:

WHY DO TAX GUYS GET INVOLVED?

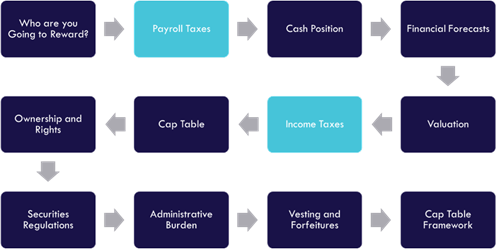

Incentive Plans perform when implementen well. This means the underlying fabrics need to be overlayed properly. And tax can be a quarterbacking factor. For example: the management goals and the ‘incentivize demographics’ may influence which plans are shortlisted, financial forecasts for the company and staff may determine which ones stay, and tax & legal provisions may determine the final pick.

Questions you may therefore want to think about are:

- Who do I want to incentivize?

- C-Suite? Management? Specific Depts? Everyone?

- What would incentivize them?

- Cash? Equity? Having a say? Sharing in Value?

- What goals do I want to achieve?

- Value Growth? PRL? Retention? HR Perspectives?

- Am I building for Cashflow or for an Exit?

- How can I link the goal to the Incentive?

- What does my forecast look like?

- What are the tax consequences?

- How much cash do we need and how much do we have?

- How do we want to govern the plan?

- Entry Clauses? Vesting Schemes? Leaver Clauses?

- Are we going for dashboarding?

- What will the plan look like for Investors?

- Do we have any live promises and expectations?

Any Incentive Plan design process will generally start with establishing what company goals the incentive plan should encourage, who the persons are that should be involved, and where the cash and time limits lie.

More often than not, taxation has a significant influence on what’s possible and what works. And as the field of tax is also closely intertwined with the company’s financing, cashflow forecasting, legal and HR processes, the ‘tax desk’ is a common platform to quarterback the design process from:

An ESOP Show at our Amsterdam Office as part of the Amsterdam Tech Week:

…and at our The Hague office as an insight’s session for lawyers:

And importantly: we also have an EIP in place ourselves – happy faces!

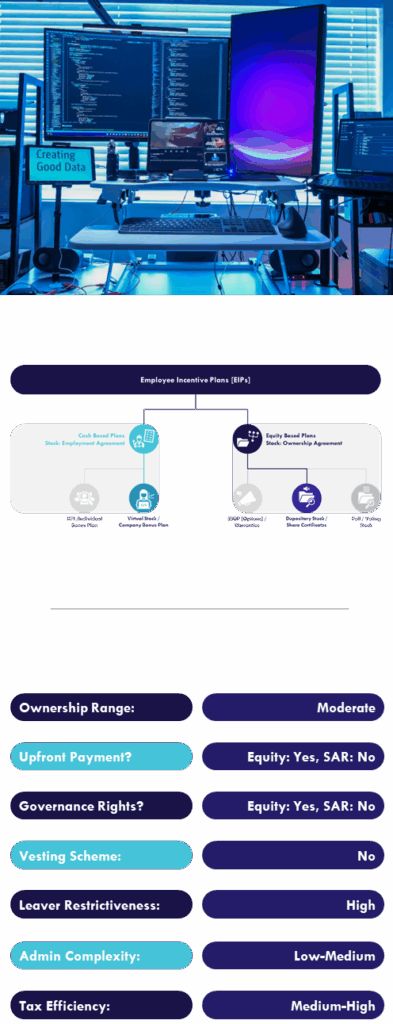

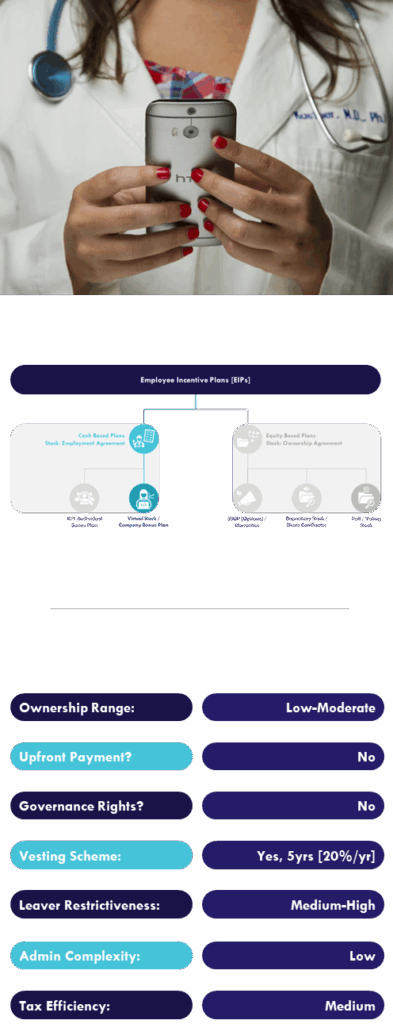

CHAPTER 2: THE 5 TYPES

Compacting the endless varieties into a simple tree.

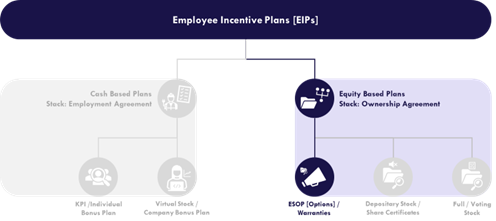

THE PHYLOGENETIC TREE OF EIPs

To get started we walk through our ‘Big 5’ Types of Employee Incentive Plans [EIPs]. This section serves as a practical primer to help contextualize the more technical discussion that follows. While the range of possible Incentive Plans is virtually limitless, listing every known variation would be both impossible and unhelpful. Instead, we propose a structured starting point: five archetypes of EIPs, which we’ve mapped out in a comprehensive, species-tree-style mind map.

These five ‘main types’ are not exhaustive, but they offer a useful framework for initial exploration. The real substance of any Incentive Plan lies in its specific conditions and implementation. It’s the tailoring to how a basic model is adapted to fit a company’s goals, culture, and workforce, that ultimately determines its effectiveness.

Broadly speaking, we distinguish between two foundational categories:

- Cash-Based (Non-Equity) Incentive Plans, and

- Equity-Based Incentive Plans.

Cash-Based plans are typically embedded in the employment contract, creating a direct and organic link between employment and incentive.

Equity-Based plans, by contrast, are governed by a separate equity agreement, meaning the relationship between the company and the participant is shaped by property law rather than employment law.

From a tax perspective, returns on Non-Equity plans are generally treated as bonus wages and taxed accordingly. Equity-Based plans, on the other hand, may generate returns on capital, unless anti-abuse provisions reclassify those proceeds as wages. That said, tax and legal considerations, while important, are not usually the primary drivers of Incentive Plan design. Business strategy and behavioral psychology tend to lead the way. The legal and financial logistics should support—not dictate—the company’s commercial and people objectives. An Incentive Plan only works when it reflects those goals clearly and credibly.

TYPE 1: THE KPI / INDIVIDUAL BONUS

A KPI Bonus Plan triggers individual top-up payments when set personel goals are met. Common examples are bonus payments linked to individual sales targets, billable hours logged, or technical milestones hit [for instance: being granted a patent or reaching a next PRL]. KPI Bonusses are the most commonly seen type of Incentive and are generally what people refer to when they speak of a ‘bonus’.

The Pro’s and Cons:

KPI Bonus Plans are easy to implement and can be highly targeted to incentivize very specific efforts. The cash-centricity of the incentive can be particularly interesting to certain staff demographics.

Where the two conflict, KPI Bonus Plans incentivize personal goals over group or company goals. Also: a KPI being hit can trigger a bonus being due, without necessary recourse to the cash position.

How is it Taxed?

Bonus Payments are taxed as top-up wages, meaning the gross bonus is subject to the employee’s marginal Income Tax rate under the ‘Box 1’ regime, which is effectuated through Wage Tax withholding first. Said gross payment is deductible from the employer’s Corporate Income Tax base [with a €700k salary cap].

THINGS TO THINK ABOU:

The natural ‘talking points’ are what goals should be incentivized, what the bonus amount looks like [lump-sum and binary, gradual or bracketed, percentual?] and – most importantly – when payment is due. Note that if the contractual KPI is met, the staff member has a legally enforceable claim – so mind cash when drafting the plan.

Conflicting Interests:

KPI Bonus Plans can be implemented company wide, department wide, or even more narrowly like per individual.

When implementing different KPI Plans, it is important to ensure they do not unintentionally conflict or create opposing interests;

For example: if an Order Picking department is awarded a KPI Bonus based on order accuracy regardless of output volume while a Sales Department is awarded a KPI Bonus based on Sales Volume regardless of turnaround times, order-to-delivery times may increase, and customer satisfaction may drop.

Cashflow Caveats:

Also, Companies should consider the interaction between Bonus Clauses and the Company’s cash position. As the clauses are carried by the Employment Contract, a direct wage obligation arises when pre-formulated targets are met absent any wording about timing stating the opposite.

So: even though it negatively impacts a Bonus Plan’s certainty and objectivity, Companies may wish to add wording covering the timing and conditions of Bonus Payments, like a link to the Company Cash position or a year-end cycle, to avoid creating strongly positioned wage debts with adverse consequences when the cash isn’t there…

The Solution: Run Clauses as Scenarios in Excel vs. Cashflow Forecast!

By putting the KPI Bonus plans into an Excel File and running wordings as scenarios in your Cashflow Forecast, we can verify their outcomes both for Staff and Company.

TYPE 2: VIRTUAL STOCK / TEAM BONUS PLAN

A virtual Stock Plan creates top-up wage potential based on team rather than personal performance. Virtual Stock Plans, Profits Pools or Stock Appreciation Rights are bonus wage plans that are linked to Shareholder-level metrics, like profits and capital gains [Virtual Stock] or Company Value movement [SARs]. They ‘mimic’ equity but form payroll instruments.

The Pro’s and Cons:

Should the two conflict, these plans incentivize group-think over personal interests. These plans are easy and flexible to implement, while the equity-tracking element still gives a sense of ownership.

As individual performance is no longer the marker, a threat of freeloader-effect lurks. However, one may argue that to be an HR issue rather than an EIP issue. Also: these plans do not necessarily have a cash link – which holds true for SARs especially.

How is it Taxed?

Bonus Payments are taxed as top-up wages, meaning the gross bonus is subject to the employee’s marginal Income Tax rate under ‘Box 1’, which the employer should withhold as Wage Tax. The gross payment is deductible from the Corporate Income Tax bases for the employer.

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT:

The natural ‘talking points’ are what goals should be incentivized, what the bonus amount looks like [lump-sum and binary, gradual or bracketed, percentual?] and – most importantly – when payment is due. Note that if the contractual KPI is met, the staff member has a legally enforceable claim – so mind cash when drafting the plan.

Choosing for Team Goals or individual KPIs:

Whether a Company Wide marker works better for your targets or an individual one, depends heavily on which departments are involved and your Company culture.

For decentralized organizations with intertwined functionalities, Company-wide goals can encourage staff to find where they are most needed and organically eradicate . However, if ‘throttle feel’ becomes too distant, using Company-wide Goals as markers may give rise to the ‘Freerider Effect’.

The Freerider Effect:

The most often heard case against non-individualized KPIs is the ‘Freerider Effect’; an effect that can arise when people have Bonus exposure regardless of their efforts,

As per the Corporate Finance Institute: A free rider is a person who benefits from something without expending effort [for] it.

We emphasize that any freerider may primarily be an HR-issue, and not an Incentive Plan issue, and trying to address the risk through financial parameters or formulas can sour the well.

Add Cash Caveats:

A well-implemented Virtual Stock Plan can entice ownership in a relatively un-complex way. As any profit right does become a ‘bonus’ and therefore a wage right, it is imperative to add some mindful wording to avoid incurring debts the Company cannot cash. So, here too: Excel is your friend! Run the scenario’s and verify the workings.

TYPE 3: EMPLOYEE STOCK OPTION PLAN [ESOP]

Under an ESOP, employees have tights to obtain company equity against a pre-determined price [the ‘Strike Price’] upon an exercise event. An ESOP that is ‘in the money’ [Strike Price < Share Value] leads to an exercise gain, then stock-ownership. This allows companies to give their employees ‘equity exposure’ without going through the often more complex motions of actually transferring equity.

The Pro’s and Cons:

ESOPs give broad involvement with the company and its value, even before equity has actually been extended, which can be a complicated procedure. But until then, there is no cash event.

ESOPs are more popular than they are tax-friendly [this appears to be a US-trickle down effect]. Also: the deferral of the equity event may create the illusion that the instrument is simple. Note that a post-strike framework should still be drafted, to govern later stock-ownership!

How is it Taxed?

The ESOP-part that involves granting or owning the option is not a taxable event; in order to avoid complicated schemes where the call-option needs to be valued [BSM Method?], taxation is deferred to exercise or transferability. Any gain upon such an event is taxed as a wage, the subsequent share ownership follows the stock systematics.

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT:

An ESOP can be implemented ‘quick and dirty’. If the exercise event is foreseeably somewhat far away, this buys time to implement the more complicated stock ownership framework. Do note that this still requires some thought. And: note that an exercise upon Exit- or Equity Event directly followed by a drag-along, is economically just a very paperwork-heavy variety of what could equally be a SAR!

Picking an Exercise Event:

Stock Options generally have a fixed exercise price, as a result of which the incentivized Employees have an interest in the Company Stock Value ahead of actually being transferred any Stock Units. Until the Options are exercised, however, the Employees are not in fact Equity Owners, and any ‘in the money’- amount of the Option upon exercise is taxed as a Wage benefit in kind.

Because of the associated and deferred tax exposure, Companies often pick an Exit Event as the Exercise Event, meaning the Options can be exercised [and the underlying Stock Units can be obtained] when external capital is raised, effectively pushing the tax exposure to the Investors.When the resulting Stock is subject to a Drag-along provision forcing the Employee to sell the freshly obtained Stock Units directly to the Investor in the transaction, the tax effect is that essentially an admin-heavy Stock Appreciation Right has been implemented.

That’s why it is important to consider the relationship between an ESOP and a SAR; save ‘psychological considerations’, ESOPs have an added financial value mainly of they can be exercised regardless of Exit Events, or if the Stock Units can be retained after one.

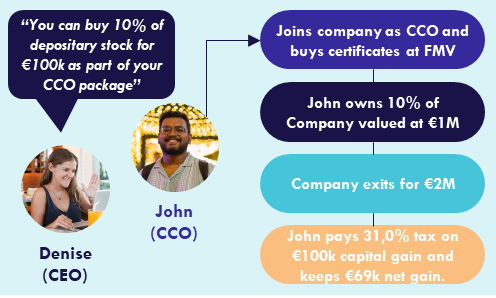

TYPE 4: DEPOSITARY STOCK PLAN [SHARE CERTIFICATES]

With a Depositary Stock Plan, employees become equity owners but not shareholders, separating capital rights from from control. Full stock comes with two types of rights: [1] the ‘Legal Rights’ [meeting & voting, control related] and [2] the ‘Economic Rights’ [dividends & capital gains].

This plan involves ‘splitting’ such stock units into two. The actual shares are held by a Shareholder Trust and the voting rights are exercised by its board, while the stock’s derivative [the Depositary Share] is held by the staff member. This separates the ‘cap table’ from the ‘control table’. The derivatives are taxed as stock.

The Pro’s and Cons:

Depositary Stock keeps company control compact, avoiding the ‘huge cap table pitfall’. For high-performing stock, equity ownership is more tax-friendly than bonus instruments. And: equity plans are involving.

Any equity-based plan requires mindful contracting, as ownership has no natural link to employment. Equity transactions also require often some financial design to avoid taxable benefits or lucrative stakes.

How is it Taxed?

Equity instruments have two relevant chapters: [1] the equity transfer and [2] the equity ownership. If a staff member can obtain the equity at an implied or explicit discount, that discount is taxable as wage in kind. The subsequent equity income falls under the capital tax regimes; the flat rate Box 2 regime for ≥5% direct stakes and the lump-sum Box 3-regime for <5% portfolio stakes.

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT:

The framework for entering, sitting on, and leaving the cap table!

Control versus Ownership:

Under a STAK-plan, the incentivized staff is fully involved on the cap table but does not have the associated control. Note that the effect is not the same as issuing non-voting stock, as such stock still has meeting rights.

As a result, company control remains more compact, and staff is not legally involved in the underlying decision-making process. This is often perceived as a positive factor for the company’s ‘investability’ as complex shareholder procedures are often detrimental.

At the same time, certain company cultures may see staff value ownership specifically and even prefer it over financial gain when presented with the choice, while simultaneously some company structures [Steward Ownership] would want all decision-making processes to be as vast and inclusive as possible.

Depositary Stock performs like, and is treated as Equity, just like Full Stock:

Either way, it is important to note that Tax Law looks at ‘economic ownership’ and Depositary Stock is treated as an Equity Instrument as is Full Stock, as it economically operates the same.

As a result, implementing a Depositary Stock Plan generally involves a Transfer of Equity which requires transaction parameters, and a subsequent ownership creating both Upside and Downside risks.

Dashboarding & Keeping Track:

Depositary Stock can be transferred without a Notary involved. This adds flexibility but may create the risk that Unit Ownership becomes ‘’fuzzy’. Therefore, dashboarding software should be considered.

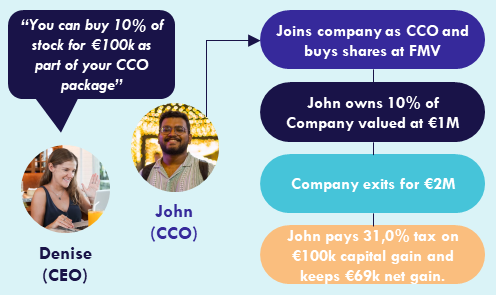

TYPE 5: FULL COMPAMY STOCK / STOCK OWNERSHIP PLAN

Company Stock Plans involve full ownership of company shaes. The incentivized staff member will have a say in the company and a stake in its capital.

The Pro’s and Cons:

Equity-based plans are generally taxed friendlier than bonus plans, especially when the equity is high-performing. Full stock is the most involving of all incentive plans.

Any equity-based plan requires mindful contracting, as ownership has no natural link to employment, and the equity transfer generally requires some financial design. Broad-based full stock plans can make the company cap table complicated and less investor attractive.

How is it Taxed?

Equity instruments have two relevant chapters: [1] the equity transfer and [2] the equity ownership. If a staff member can obtain the equity at an implied or explicit discount, that discount is taxable as wage in kind. The subsequent ownership and disposal are generally subject to the capital tax regimes; the flat rate Box 2 regime for >5% direct stakes and the lump-sum Box 3-regime for smaller [portfolio] stakes.

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT:

Also, the framework for entering, sitting on, and leaving the cap table; full voting stock specifically creates a more expansive decision-making process, meaning this instrument should be reserved for those who should actually get a say. Those whose input is valuable and whose buy-in is important.

Control versus Ownership:

As opposed to the Depositary Stock Plan, a Company Stock Plan would include involvement in the decision-making process of the company. This can generally be suitable for staff more closely involved with managerial roles

Things to think about when implementing a Full Stock Plan:

Implementing a Full Stock Plan involves a Transfer of Equity which requires transaction parameters, and a subsequent ownership creating both Upside and Downside risks.

Dashboarding & Keeping Track:

Full stock requires transaction parameters that need to be determined and it can not be transferred without the involvement of a Notary. Therefore, it requires substantive documentation.

CHAPTER 3: THE TAX FRAMEWORK

Incentive Plans come with corporate and personal tax effects, and these can set the playing field.

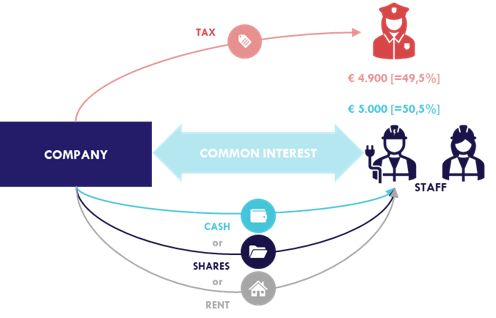

Incentive Plans align employee and company interests and sit within the employment ‘stack’. This typically involves a Wage Tax element followed by Personal Income Tax for the employee, and a Corporate Income Tax (CIT) element for the company. If the plan spans borders, Tax Treaty considerations may also apply.

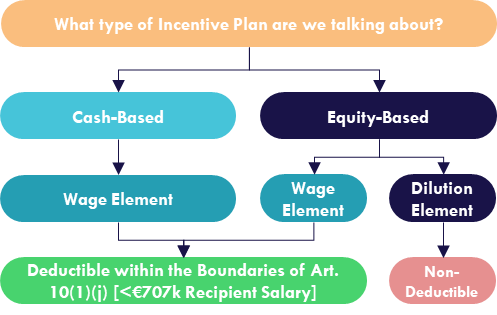

In the Netherlands, Incentive Plans take various forms [more on that later], each with distinct tax and legal implications. The five main types range from straightforward cash bonuses to complex equity-linked arrangements. While KPI Bonuses are taxed with Personal Income Tax [after Wage Tax Withholding] as regular income, triggering tax on payment, equity-based plans may be taxable at grant, vesting, or exercise, depending on their structure and applicable rules, after which specific tasset holding taxes may apply as well. Due to such strategic impacts, Tax is rarely the sole driver in plan design, but it does shape what’s viable.

From a Corporate Income Tax perspective, deductibility depends on both general principles and specific limitations. Article 10(1)(j) of the Dutch CIT Act, for instance, restricts deductions for share-based compensation, especially when linked to value increases and high-income employees (above €707.000). However, if shares are granted net—meaning the employer covers the Wage Tax—the tax component may still be deductible. This makes plan structure and employee income levels key factors in the company’s tax position.

Cross-border cases add complexity. When employees move or work across jurisdictions during vesting, taxing rights must be allocated correctly. Tax treaties and OECD guidance help prevent double taxation, but employers must apply sourcing rules carefully—especially with mobile or remote workers.

Ultimately, a well-designed Incentive Plan balances motivation, legal enforceability, and administrative feasibility, with tax as a structural backdrop. Virtual Stock Plans or Stock Option Plans, for instance, simulate ownership without equity transfer, suiting startups or complex shareholder setups. True equity plans like Company Stock or Depositary Stock can support long-term alignment but require careful legal and tax planning.

The Four Main Tax Panels:

PANEL 1: EIPS AND CORPORATE INCOME TAX

When designing Employee Incentive Plans, companies often ask whether the associated costs are deductible for Corporate income Tax [CIT] purposes. But the more relevant question is: does the incentive actually result in a cash cost to the company. Deductibility may be legally restricted, but also practically irrelevant. This section clarifies when deductibility matters, when it doesn’t, and what companies should focus on instead.

What Does Dutch Tax Law Say About Deductibility?

Under CIT Law, expenses are generally deductible if they are incurred in the course of business operations and are not explicitly excluded through a specific tax provision. Article 10(1)(j) of the Dutch CIT Act is such an exclusion: it disallows the deduction of costs related to the issuance or grant of shares, stock options, or similar rights to employees. This includes both actual equity and rights whose value is tied to equity performance. However, this rule only matters if the company incurs a real, cash-based cost. And for costs classified as wage still, deduction is only restricted if the recipient earns €707k or more.

Why Dilution Is Not Deductible, But Also Not a Cost:

If a company grants shares or options that dilute existing shareholders, this dilution is not deductible, but it also doesn’t cost the company anything in cash. The economic cost is borne by the shareholders, not the company. Therefore, the lack of deductibility is a non-issue in these cases. Rule of thumb: if the company doesn’t pay anything out of pocket, there’s nothing to deduct.

When Does Deductibility Actually Matter?

Deductibility becomes relevant when the company does incur a cash cost, such as when it pays Wage Tax on behalf of the employee. For example, in a Net Share Grant, the company issues shares to the employee and pays the Wage Tax due on the benefit which equals the stock value -/- the amount the employee paid for it [generally nil in this case]. That Wage Tax payment is a real expense, and that portion is deductible. Similarly, if a cash bonus is paid, it is both a cost and deductible.

Does that make Cash-Based Instruments a Better Choice?

Not necessarily. While cash-based incentives are generally deductible, they also **require actual cash outlay**. Structuring an incentive as a cash bonus just to achieve deductibility is not a best practice—because you’re trading a non-cash dilution (which costs nothing) for a cash expense (which costs real money), even if it’s deductible. **Rule of thumb**: don’t chase deductibility if it means creating a cost where there wasn’t one.

What About High Earners and Special Limits?

There is a specific restriction for high earners: if an employee earned more than €707.000 in the previous year, and the incentive’s value is ≥70% linked to share price, then even the Wage Tax component is non-deductible. This rule targets equity-heavy compensation for top executives and should be factored into plan design for senior leadership:

Best Practice 1: Focus on Substance, Not Just Tax

The most effective approach is to design incentive plans that align with your business goals and cash flow realities. If you want to avoid cash outlay, equity-based instruments may be preferable, even if not deductible. If you do incur Wage Tax on equity grants, ensure that portion is properly documented and deducted. Rule of thumb: optimize for business impact first and treat deductibility as a secondary benefit, not a design driver.

Best Practice 2: Document Valuations

If deductibility is a factor, companies often align the incentive’s tax treatment with employment income. This includes clear documentation, robust valuation methods, and payout structures that avoid capital income classification. Seeking an Advance Tax Ruling (ATR) from the Dutch tax authorities can provide certainty on this and prevent disputes. In practice, many companies opt for virtual instruments or cash-settled plans to maintain deductibility while still offering meaningful rewards.

PANEL 2: EIPS AND WAGE TAX

Whether the plan involves cash, virtual equity or actual shares, the key question is: when does the employee receive a taxable benefit and how is it valued?

In the Netherlands, the Wage Tax treatment of employee incentive plans depends on the nature of the benefit and the moment it becomes taxable.

What Triggers Wage Tax?

Wage Tax is due when an employee receives a benefit that is considered income from employment. For cash bonuses, this is straightforward: the tax is due when the bonus is paid or becomes payable [whichever comes first].

For equity-based instruments, the timing is mores squishy; any ‘benefit’ [e.g. a discount on an equity grant] becomes taxable when the employee acquires the economic ownership. This is typically the moment of transfer, but can be a later moment if, for instance, certain vesting schemes or suspending conditions apply. Either way, the wage-taxable amount is the benefit derived by the employee which can lead to gross-ups absent any tax clauses.

How Are Different Instruments Treated?

- Cash Bonuses and KPI-Based Rewards are fully taxable as wage [top-up payments] when they are paid or become payable [whichever comes first];

- Virtual Shares / Phantom Stock: same thing, cash-based plans are relatively straightforward from a domestic Wage Tax perspective.

- Stock Options: Under the new 2023 regime, companies can choose to tax at either (i) the moment of exercise or (ii) the moment the shares become tradable. This flexibility is especially useful for startups where liquidity is limited, but later taxation can also mean higher values so higher taxable base.

- Depositary Receipts and Shares: Taxed when the employee gains control or economic ownership. If shares are granted at a discount, the discount is taxable as wage. But an FMV share transaction is not a wage tax event.

Are There Special Rules for Startups?

Yes. The revised stock option regime introduced in 2023 is announced to be improved as per 2027 for ‘startups’, which have yet to be defined. The improvement entails a 35% base exemption on the ESOP-related gain [in the money amount] with taxes deferred until the shares are sold rather than acquired or unlocked.

Mind the Gross-up!

A central concept in managing Wage Taxes in an EIP context is that the code seeks to capture the in-hand benefits for employees. In other words: if an employer wanted to make sure their employee had €5.000 cash in hand, against a marginal income tax rate of 49,5% they’d need to wire them [100%/(100,0%-49,5%)]*€5.000 = €9.900 gross. This calculation is called the gross-up.

The same rule goes for non-cash items, like those with a savings element. Paying rent, or groceries. Or: shares. If an employee therefore received a discount on any shares, the in-hand value they can sell it for on the market determined the net part of the payment and should be grossed up to determine the wage tax due. So: any employer wanting to grant their employee €5.000 FMV worth of shares for free, should –absent any tax pushdown clauses– be aware that they are also due €4.900 of wage tax in that same month.

Best Practices for Managing Wage Tax

- Document the moment of taxation clearly, especially for equity instruments, as this can be squishy.

- Use and substantiate fair market valuations to determine taxable amounts & gross-ups due.

- Consider net vs. gross grants & tax clauses: if the company covers the tax, the gross benefit increases.

- For startups specifically: consider opting into incentivizing regimes to avoid taxing liquidity constraints at both a company and an employee level.

VALUATIONS: FAIR MARKET VALUE AND DISCOUNTS

Wage Tax is generally one of the most pivotal tax considerations when implementing an Equity-based plan. The Dutch Wage Tax treatment of employee incentive plans depends on the nature of the benefit and the moment it becomes taxable. And for equity stakes, this is generally the moment a discount or grant is transferred, due to the technical parameters of ‘wage’.

What is ‘wage’?

The Wage Tax Act defines taxable ‘wage’, in short, as everything that is derived from an employment relationship, current or former. Through parliamentary history and case law, we know that this means that any benefit that a (holding/intermediary company of an) employee receives from (a group company of) the employing company, can be considered to fall within the scope of that definition.

In the following paragraphs we no longer mention the taxability of the indirectly obtained benefits from group companies etc. Gross salary, of which the employee only gets the after-tax part, is but one element. Bonus payments (including SARs) obviously fit the description. But benefits ‘in kind’ (instead of ‘in money’), like shares, are also covered, as you probably know by now.

How is it valued?

Pursuant to the Wage Tax Act, non-monetary benefits [i.e. benefits in kind] are taken into account against ‘the value that can be attributed thereto within the economy’. This is a quite literal translation of the Dutch fiscal valuation prescription “waarde in het economische verkeer” [abbr. ‘WEV’], a long-standing definition that has been interpreted and given specific meaning by Dutch courts for various tax purposes.

The Supreme Court defined the WEV as “de prijs die bij aanbieding van een zaak ten verkoop op de meest geschikte wijze na de beste voorbereiding door de meest biedende gegadigde zou zijn besteed”, which translates to ‘the price that, within an acquisition context, would have been paid by the highest bidder in the most appropriate way after the best preparation’. Case law shows us that, in the case of equity instruments within the Wage Tax domain, the WEV is considered to be equivalent to the more widely known Fair Market Value [abbr. FMV].

Valuating a business enterprise

The FMV can most accurately be derived from an actual Fair Market Transaction. This would be a third-party transaction that took or will take place at a moment close enough to today for its value to be accurate still. We call this a ‘reference transaction’.

In absence thereof, however, the golden standard for valuating a non-listed entity is the Enterprise Discounted Cash Flow [‘DCF’] method [‘DCF]. Its strength is that it’s forward-looking and income-based, rendering it quite dynamic. The rationale is simple: the method bases the valuation of a business on the premise that the value is determined mainly by future operational, free cash flows. This is also referred to as the ‘Free Cash Flow to Firm’.

Going from enterprise value to equity value

In the Free Cash Flow to Firm (Enterprise DCF), the company is valued ‘cash and debt-free’, so to say. Interest payments (and corresponding CIT) are not taken into account to project the free cash flows, because interest-bearing debts (and debt-like items) are subtracted in the ‘equity bridge’ to go from the enterprise value to the equity value, which comprises the company’s total share capital. It is from this value that the FMV of the employee’s share package is to be derived.

Usually, an employee is met with transfer restrictions and a minority stake. Both of these aspects justify a downward adjustment from the [stake percentage * equity value], in order to arrive at the FMV of the employee’s shares.

Case law indicates that such adjustment may range to approx. 40%, depending on the case specifics.

When does the employee receive taxable benefits?

Pursuant to the Wage Tax Act, wage is considered to be received the earliest of (i) the moment at which it is paid, credited, made available or becomes interest-bearing, or (ii) the moment at which it becomes ‘receivable and collectible’.

To the extent that an employee does not pay (or remain indebted) the FMV of shares granted to them, the abovementioned definition of the taxable moment entails that that FMV-excess [benefit in kind] is taxable the month in which the employee acquires the economic ownership thereof. This moment is usually perfectly synced with the transfer of the legal ownership.

The typical vesting scheme qualifies as a phased ‘suspensive condition’, which renders the employee’s right [after signing the SPA] to the legal (and economic) ownership of part of those shares legally unenforceable. Hence, the part of the shares that is still hidden behind such vesting conditions, has not yet been ‘received’ by the employee for Wage Tax purposes. This means that the vesting moments constitute the taxable moments (to the extent that the employee has not paid or remained indebted the FMV thereof), and that the corresponding FMV is determined at those later taxable moments as well.

This is the reason that some companies, if they expect to grow in value, choose a ‘reverse vesting scheme’. Pursuant to this mechanism, all of the shares fully transfer immediately, but (part thereof) must be transferred back to (the shareholder(s) of) the company if the reverse vesting conditions are not met. This way, the taxable moment (if any) is frontloaded, resulting in a lower Wage Tax due to a still low company value relative to the expectation.

The ‘Gaming Element’ to Equity Plans:

the earlier in the hockey-stick a taxable Equity Flip takes place, the bigger part of the ride takes place in the equity regime. But the buy-in, does mean there’s capital and/or loans at risk, and taxes can be due regardless of cash proceeds. So: place your bets!

PANEL 3: EIPS AND PERSONAL INCOME TAX

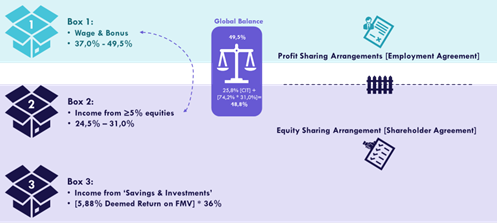

In the Netherlands, the Personal Income Tax [PIT] treatment of Employee Incentive Plans depends on the nature of the benefit and the moment it becomes taxable. The Dutch Personal Income Tax Act uses a three-’Box’ system to categorize income, and each type of incentive plan may fall into a different box depending on its structure and execution.

What Are the Three Boxes of Dutch Income Tax?

- Box 1: Income from work and home ownership (e.g. salaries including bonuses and benefits in kind, income from sole proprietorship and certain gig or anti-abuse income) is taxed at progressive rates up to 49.5%.

- Box 2: Income from ‘substantial shareholdings’ (≥5% personal stakes in a company or share class) is taxed at 24.5%–31%.

- Box 3: Income from ‘savings and investments’ (e.g. savings and checking accounts but also ‘portfolio’ so <5% shareholdings as well as most receivable) is taxed at a flat 36% on deemed returns [set to switch to actual returns as per 2028].

A ranking rule applies: if income qualifies for a ‘source of income’ defined under the Box 1 chapter, it is swept up there and cannot be taxed in Box 2 or 3 despite potentially fitting such a description equally.

How Are Different Incentive Instruments Taxed?

- Cash Bonuses and Virtual Shares: always taxed in Box 1 as employment income. The employer must withhold Wage Tax at source.

- Stock Options (ESOPs): taxed in Box 1 at the moment of exercise or when the shares become tradable (under the 2023 regime). The taxable amount is the “in-the-money” value, so ultimately the discount realized on the share acquisition.

- Depositary Receipts and Full Shares: If acquired at a discount, the discount is taxed in Box 1 as a benefit in kind. Subsequent gains fall under Box 2 (if ≥5%) or Box 3 (if <5%).

Note re. Lucrative Interests: if the equity is highly leveraged or linked to performance (e.g. carried interest), it may be reclassified to Box 1 as bonus-income under anti-abuse rules, even if it looks like capital income.

When Does Tax Become Payable?

Tax is due when the benefit is:

- Paid or becomes payable (for cash-based plans);

- Exercised or becomes tradable (for options), or;

- Acquired at a discount (for equity), or;

- When real (Box 2) or deemed (Box 3) returns flow from the equity

This can create cashflow mismatches, especially for equity-based plans where the employee owes tax before receiving liquidity.

What Are the Planning Opportunities?

- Box 2 vs. Box 3: high-growth equity may benefit from Box 3’s deemed return system as its real ROI may far exceed the deemed 6,X% returns, but Box 2 offers more predictability and deferral options.

- Use of Holding Companies: employees can structure their participation through a personal holding to access Box 2 and apply the participation exemption, allowing for tax free exits and deferral on Box 2 income as they can control its drip.

- Avoiding Lucrative Interest Classification: ensure equity is not overly leveraged or tied to performance to avoid Box 1 reclassification, or structure through Box 2 to use the ‘escape hatch’ of a pass-thru indirect stake.

PIT ZOOM-IN 1: ESOPS AND PERSONAL INCOME TAX

The Dutch ESOP Gameboard is set to be improved as per 2027

ESOPs can be a great EIP choice, especially for startups and scale-ups looking to reward long-term commitment without draining cash. That has made them somewhat of an international Golden Standard for growth companies. But the Dutch tax rules have been a bit of a maze, and not always very favorable. Thankfully, the Dutch government is reshaping the map.

The Old Game: Tax at Exercise (or Later)

Under the exiting regime, companies can choose when the ESOP becomes taxable:

- Default: Box 1 Tax [Wage Tax] is deferred until the shares obtained through calling the option become tradable (with a 5-year cap post IPO).

- Optional: Through a mutual declaration, the Box 1 Tax [Wage Tax] can be frontloaded to exercise (when the employee obtains the shares), sometimes allowing for a lower total tax charge but often requiring that the employee has liquidity to pay the tax

The New Game: 2027 and Beyond

New ESOP-systematics have been announced for 2027, bringing the Dutch tax framework closer to that of highly-ranked UK and USA. Here’s what’s changing:

- No tax at grant: Still true. Options are not taxed when granted.

- No tax at exercise: That’s new. The taxable moment shifts.

- Tax at sale: The employee pays tax only when they sell the shares, and only on the actual gain with a 35% exemption for the gain, aligning the effective Wage Tax charge with a Box 2 capital gain.

What’s the Catch?

- Only for qualifying startups and scale-ups (criteria to be finalized).

- Anti-abuse rules will still apply, especially for heavily leveraged or “lucrative” structures.

- Box 1 vs. Box 2 or 3: proceeds from the obtained shares can still fall under Box 1 if the structure is deemed too salary-like / highly leveraged.

What Should You Do Now?

- Design with 2027 in mind: If you’re setting up a plan now, consider how it will age and whether you can benefit from the better rules.

- Stay tuned: The final legislative text is expected in 2026. Flexibility is key.

Our 2024 studies of the Dutch ESOP Tax Framework for the Dutch Ministry of Finance showed that the Reward over Risk-factor for Dutch ESOPs was significantly low as compared to ‘Startup Competitor’ states, due to early and non cash-linked taxes on the benefits along with high tax rates. This has led to a newly anounced ESOP improver for Startups/Growth Companies which have yet to be defined:

PIT ZOOM-IN 2: THE ‘LUCRATIVE INTEREST PROVISION’

Targeting the ‘Carried Interest Loophole’ in leveraged share structures.

Why this matters

In the world of incentive plans and equity structuring, the Dutch “lucratief belangregeling” (Lucrative Interest Provision) is a critical checkpoint. Originally designed to curb excessive private equity-style remuneration [carried interests], it now casts a wide net over many modern incentive structures.

The origin story: from Crisis to Control

The Lucrative Interest Provision was introduced in 2009 as part of a broader legislative package aimed at taxing “excessive benefits.” Its goal? To prevent disguised salary payments, especially in leveraged management buy-ins, from slipping through the cracks as lightly taxed capital gains.

The provision targets equity instruments with disproportionate upside relative to the capital at risk. Think: 10x returns on a €1 buy-in. If it looks too good to be true, the Dutch tax authorities may reclassify it as wage income.

The Core Mechanics

At its heart, the provision says:

If an employee or manager receives an equity interest that is highly leveraged, performance-linked, or non-arm’s-length, the resulting gains may be taxed as bonus income in Box 1 (up to 49.5%) instead of equity income in Box 2 or 3 (24.5–36%), while the payment does not dip into deductible wage for the company. This leads to a two-layered tax charge that can compound into a 62,5% tax rate on the proceeds derived from such stakes.

The question, then: how do we discern between non-market ‘should be bonus’ income versus genuine equity income as a market grade return on providing risk-bearing capital?

Triggers include:

- Hurdle shares with low or no buy-in

- Ratchet shares or carried interest structures

- Performance shares with asymmetric upside

- Synthetic equity with equity-like returns but no real risk

- A Return on Invested Capital that is in excess of 10:1 compared to the returns that other investors made [is this market grade?]

Safe Harbors & Escape Hatches

Not all hope is lost. The provision includes exceptions and structuring options:

- Fair Market Value Buy-In [theoretic at best]If the participant pays full FMV for the equity, the provision generally does not apply (because then, how can there be leverage). However, this is squishy, because how does one value a carry?

- Dispreference Clauses [tricky]Shares with a dispreference (e.g. hurdle shares) can avoid Box 1 treatment if the dispreference equals less than 90% of the undiscounted FMV at grant and if the structure is embedded in shareholder agreements, not articles of association;

- Indirect Holding Structures [go-to option]If the interest is held via a personal holding company, and 95% of the proceeds are immediately on-paid, the gain may be taxed in Box 2 instead.

Practical tips for plan design:

- Document FMV using a robust valuation method (e.g. DCF)

- Avoid excessive leverage unless justified by real risk

- Use reverse vesting to frontload tax at a lower value

- Consider hybrid structures (e.g. SAR + DR) to balance upside and compliance.

The Lucrative Interest Provision is not a dealbreaker—but it is a design constraint. Like any good tax rule, it rewards thoughtful structuring and punishes shortcuts. If your plan is real, fair, and well-documented, you’re likely in the clear. But if it walks like a bonus and talks like a bonus… it probably is!

For more on the Lucrative Interest Provision, check out our blog post:

PANEL 4: INTERNATIONAL TAX

The international tax playbook for EIPs.

Why this matters

Many EIPs are designed with international talent in mind. If your team crosses borders, taxation under Dutch tax law won’t tell the full story. That’s where international tax treaties come into play. These treaties determine which country gets to tax what, when and how much.

Even though the incentive plan may be designed in one country, it can trigger tax in another – especially when an employee exercises options after relocating. Without proper alignment, this can lead to double taxation.

The Model Tax Convention

The OECD model is the global playbook for cross-border tax alignment. Here’s how it plays its part in the EIP arena:

Article 15 – income form employment:

Equity-based benefits are seen as employment income – up until the moment of exercise.

The key point here isn’t when the benefit is taxed – but where it was earned. And that means: in which country was the employee working while the economic value of the benefit was building up [i.e. the source state]? Or as the OECD states: “income is allocable to the services rendered that gave rise to the benefit”.

Therefore, a timing mismatch may occur; stock options are often taxed later than when the services were performed, but the right to tax is allocated on when and where the value was earned.

Article 10 and 13 income from capital gains:

Once employees exercise their option the next tax moment may not be an immediate exit, but a dividend.

Under article 10 of the Convention, dividends may be taxed in both:

- The country where the company paying the dividend is resident

- And in the employee’s country of residence – with a credit or exemption to avoid double taxation.

- Dividend are no longer employment income – they’re returns on capital. That means different articles, different rates, and different planning angels.

The same goes for the alienation of the Equity-based benefits after the moment of exercise or obtainment of the shares:

Any future gains from the alienation are no longer salary. The employee qualifies as an investor and any capital gains fall under article 13. Taxing rights shift to the country of residence.

Pro Rata Tracking

When an employee works in multiple countries during the period in which equity-based benefits and bonusses are earned, the OECD recommends a time-based allocation of the taxable amount:

Total gain x (number of workdays in country X / total relevant workdays). Therefore, accurate tracking of workdays is essential to get this right and avoid double taxation.

Risks to watch:

- Employees moving during earning periods

- Unclear documentation on what period the award relates to

- Countries taxing at different moments [grant vs. exercise vs. sale]

- Double taxation risk

Best practices:

- Track work locations from grant to exercise

- Use a days-worked allocation model

- Consider treaty relief if more than one country has a right to tax

- Document which periods the EIP is meant to reward

Check out our blog post for a deep dive into the ins and outs of Tax Treaties:

WRAPPING UP THE TAX GAMEBOOK

How you structure the plan determines how it is taxed, and that can mke or break the magix.

Summing up the Three-Box System:

Dutch personal income tax is sorted into three “Boxes,” each with its own logic:

- Box 1: Income from work (salaries, bonuses, benefits in kind). Taxed at up to **49.5%**. Pay as you earn.

- Box 2: Income from substantial shareholdings (≥5%). Taxed at **24.5–33%**. Sounds better but does require buy-in and is often preceded by Corporate Income Tax [meaning the combined rate on going concern profits + dividends is pretty similar to Box 1].

- Box 3: Income from savings and investments (<5%). Taxed at a *flat 36% over a deemed return. Sometimes a win, sometimes a trap, no liquidity matching.

- Rule of thumb: If it smells like top-up wages, in cash or in kind, it’s Box 1. If it walks and talks like equity, it might make it to Box 2 or 3—unless anti-abuse rules say otherwise.

The Gameboard: What Triggers Tax?

- Cash Bonusses [KPI as well as Virtual Shares or SARs]: Taxed when due or paid [whichever comes first]. Simple. Box 1.

- Stock options: Taxed at exercise or when shares become tradable (your choice under the 2023 regime). The “in-the-money” value is Box 1; the subsequent share ownership is Box 2 of 3 [absent highly leveraged setups].

- Shares or Depositary Shares: Box 2 or 3. Acquired at a discount? The discount is Box 1 [wage benefit in kinds], later gains are Box 2 or 3.

- Lucrative interests: if the equity return is almost too good to find on the open market in a business you aren’t involved with (e.g. 10x leverage versus the average of ‘regular’ share), it’s Box 1. Even if it looks like equity. But you can structure around that. It’s complicated.

The Playbook: How to Structure Smartly

- Avoid tax without cash: if the employee has no meaningful cash, it’s best not to trigger ‘Box 1 tax’ [i.e.: a tax reimbursement clause] predating liquidity events. Watch out for this with ESOPs and Equity Plans.

- Use net grants wisely: absent any wording to the contrary, benefit amounts can be considered net meaning the company pays the gross-up tax. Tax parts are deductible for CIT; equity parts are not.

- Box 2 vs. Box 3: Box 3 can be cheaper long-term, but it taxes you even if you haven’t sold. Box 2 is “pay-as-you-earn” and more predictable. There’s a cash link.

- Holding companies: want Box 2 treatment for a <5% stake? Form combined holding companies a separate share classes.

Final Word: Don’t Let the Tax Tail Wag the Dog

Tax matters—but it’s not the only thing that does. The best incentive plans are designed around people, purpose, and performance. Tax is just the seasoning. Get the recipe right, and the pie will grow.

But Remember that Tax is Part of the Recipe!

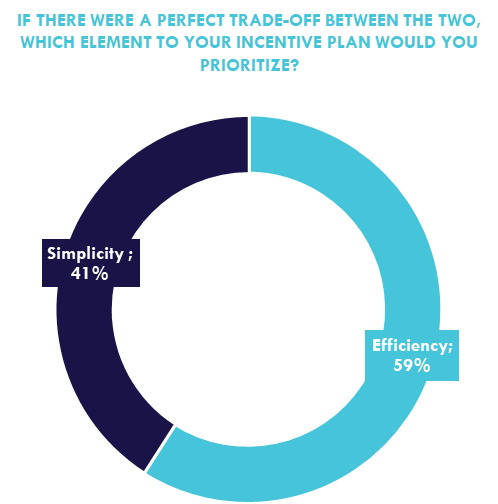

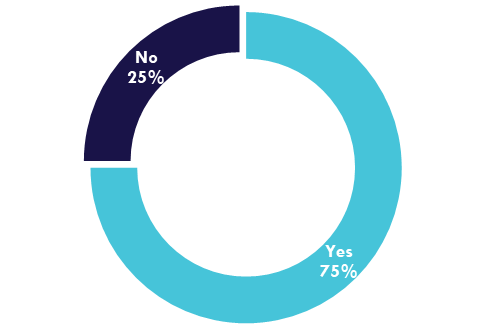

We circulated a questionnaire amongst Founders, Investors and Key Hires, and asked:

As it turns out, a plan’s efficiency [i.e.: tax friendliness / net return] is more often considered an important factor than its simplicity, meaning people are generally willing to sacrifice simplicity for a better net outcome. Tax, of course, is a big part in that and it goes without saying that a plan with a more spectacular potential payoff has a more spectacular effect.

Check out our blog post for more questionnaire-based statistics on EIPs:

CHAPTER 4: DECISION POINTS

Though no two EIPs are the same, the underlying contracts have very similar building blocks.

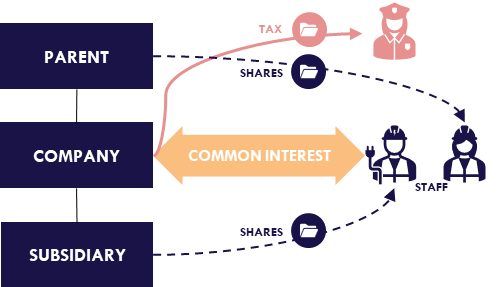

Who

The formal agreement to any EIP will first mention who is who. So: who is the issuing Company, and who is the beneficiary/participant. Although this seems pretty boiler plate, it can have a real impact which entity within a larger group issues the cash or equity effect. For instance: a cut ‘up top’ gives a more complete and diversified equity exposure but less throttle feel, whereas a cut in the local sub is more acute but often more risky. And: never forget the cross-border tax elements here. There’s always subtle differences between being paid by or having a stake in a domestic setup versus a cross border one.

‘How Much’

The next talking point is simply ‘how much’. How much cash, virtual stock or equity shall be involved, and how much –if anything– will it cost?

This too is a strategic item. The extent in which ownership is shared or concentrated has a core link to Company DNA and both the depth [size of stakes] and width [# of beneficiaries] of an EIP relates to how a business runs.

Aside from more idealistic or managerial considerations, however, cash can simply be a factor. After all: there can be an intention to make Person X a 10% owner, but if they don’t have the money to acquire the stake and Company lacks the liquidity to gift it, it becomes a matter of adjusting the envisaged stake or creating a more complex scheme.

Either way, ‘how much’ is the flesh of the matter and requires balancing Ownership remunerations, investor returns, staff acquisition and retention as well as HR Policy. Take your time for this one and model your scenario’s!

Express Brew or Slow Drip?

Once the batch size has been established, question is whether it should be transferred right out the bat, or whether it should amass over time. We call that ‘vesting’. Slower vesting gives additional reasons to stick around while faster vesting gives quicker ownership. There are endless patterns in which vesting schemes can be shaped, from linear to ‘heavy tail’.

Additionally, specific clauses can be added to adapt for events that take place or that take place unexpectedly quick. Like accelerated vesting in case of an exit, which allowing beneficiaries still earning their cut to fully capitalize on an Exit should it arise before their batch is fully mature.

Running the Shop

Though not solely or necessarily an Incentive Plan item, it’s also important to discuss how the business shall be run. Will the beneficiary have a say? An EIP can create a link between risk and influence and targets and ownership, but there’s a delicate balance with the company’s agility and the complexity of its decision-making process.

The influence element to any EIP is a crucial part of it’s messaging.

Saying Goodbye

Once the batch size has been established, question is whether it should be transferred right out the bat, or whether it should amass over time. We call that ‘vesting’. Slower vesting gives additional reasons to stick around while faster vesting gives quicker ownership. There are endless patterns in which vesting schemes can be shaped, from linear to ‘heavy tail’.

Additionally, specific clauses can be added to adapt for events that take place or that take place unexpectedly quick. Like accelerated vesting in case of an exit, which allowing beneficiaries still earning their cut to fully capitalize on an Exit should it arise before their batch is fully mature.

Sharing the Sweets

The point of an EIP, of course, is not simply the ownership or the process (although being seen and feeling valued is important), but also quite simply ‘the loot’. Any plan should at some point be intended to bare fruits, and the incentive that ticks the boxes and sticks around to secure their cut, should see their efforts rewarded. The timing and nature of these ‘sweets’ can be different between ‘build to keep’ companies [intended profit machines] and ‘scale to ‘sell’ companies [intended exit headliners] which is why the end vision is an important factor to the plan’s kick-off design.

Check out our blog post [in Dutch] for what an Exit process may look like, from pre-Exit planning to signing the SPA and closing the Deal:

BLOCK 1: WHO?

Who should be involved?

The Issuing Entity

The formal agreement to any EIP will first mention who is involved. Who is the issuing Company, and who is the beneficiary / participant?Although this seems pretty boiler plate, it can have a real impact which entity within a larger group issues the cash or equity instrument, as cross-border income or assets can trigger filing obligations in the source state, yet it may also be exempt from taxation under certain expat regimes.

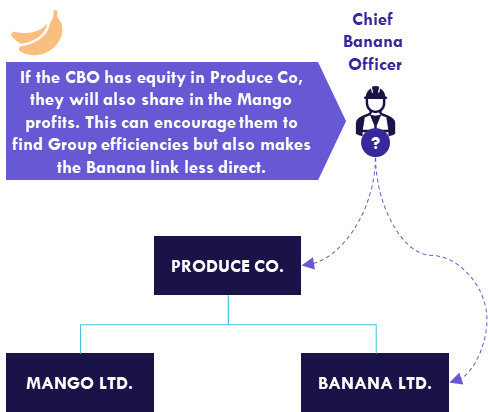

Aggregation Level

More importantly, however, pinpointing the issuing entity has an effect on the level of aggregation. Should the beneficiaries share in global profits or only in those of the local entity for which they work, or somewhere in the middle?

Implementing the Incentive Plan ‘further up the chain’ can encourage teams to aim for efficiencies, while going further down the chain gives a more direct throttle feel between the pay-out and the efforts.

The Beneficiaries: who do we Target?

It may seem obvious, but different plans can work for different people and teams. There is no need to try and fit the whole company into a single Incentive Plan, although it is possible of course. Who the target audience is, greatly impacts the decision as a CXO hire may not be properly captured or enticed by a plain KPI Bonus, whereas a young sales hire may not be inclined to pay for equity, especially if they’d not get any control rights in return for their capital at risk.

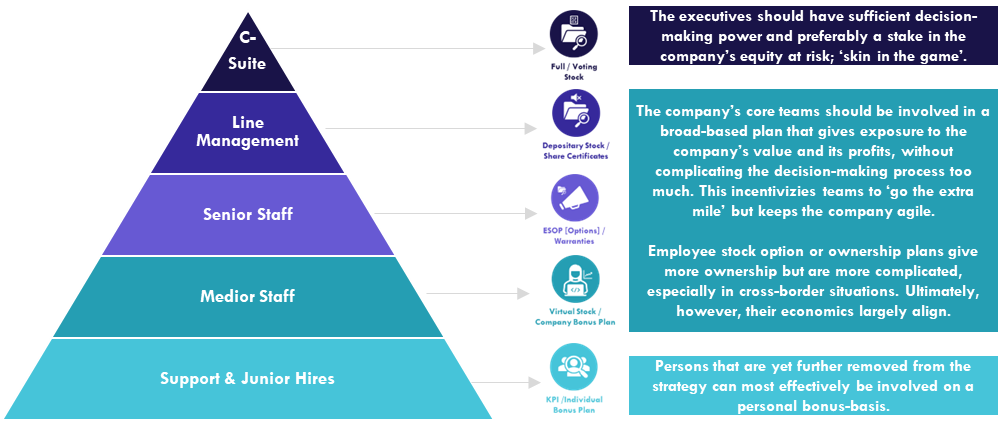

We find that generally speaking, if one were to visualize the ‘pyramid’ of seniority within an organization and rotate our ‘5 types’ overview by 90 degrees, the job titles aligns pretty well with their probable match:

Why Incentivize at the Top?

Implementing incentive plans at the consolidating level aligns employees with the broader strategic vision and long-term value creation of the entire corporate group, not just a single subsidiary. This approach reduces misalignment caused by differing performance metrics, risk profiles, and time horizons across entities. It also simplifies governance, ensures consistency in plan design, and avoids jurisdictional and regulatory fragmentation:

Unlock Collective Performance with Broader Plans

Why reward just a few when you can energize your entire workforce? Broad-based incentive plans tap into the full potential of your organization by recognizing everyone’s contribution—not just the top tier. This inclusive approach builds trust, boosts morale, and drives collaboration across departments. It turns performance into a shared mission, creating a culture where success is celebrated together—and results follow. Cover as deep a part of the ‘pyramid’ as you dare!

BLOCK 2 [THE MILLION DOLLAR QUESTION]: HOW MUCH

Seniority as a Factor

This is probably stating the obvious, but persons further ‘up the chain’ should probably have larger ‘batches’ than those with more limited strategic mandates and responsibilities. Reason being that executives would need a fitting mandate and also proper skin in the game; if they are to make decisions about the company’s capital, other investors will generally trust their diligence better if they also stand to lose significantly if things go south.

Conversely, it doesn’t seem fair or enticing to ask persons much further removed from the strategy to accept a significant capital risk, as they cannot feasibly influence strategy such that they can avoid capital losses. Notwithstanding such seniority considerations, persons with a longer tenure at the firm and ‘early joiners’ especially will generally hold larger batches. This rewards loyalty and provides a risk premium to the bold joiners.

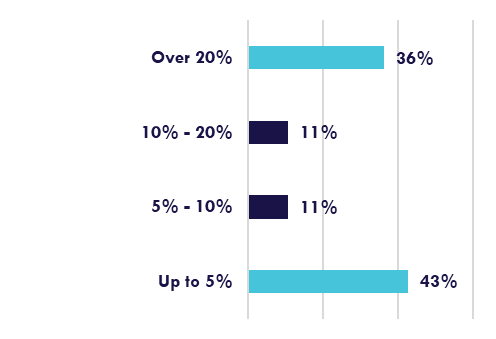

Urban legend: 15% for the Team?

Venture capital firms commonly expect startups to allocate 10–20% of their equity to employees through an option pool, with 15% being a frequently cited benchmark. This range is considered standard practice to attract and retain talent and is often a condition for investment during early funding rounds.

Although data that confirms the 15% Urban Legend is difficult to come by as companies in the VC-phase are pre-public, certain VC firms [like YCombinator and Interplay ] have published insights and/ or standard deal terms confirming this 10%-20% target, and ecosystem platforms like Carta and The Long Term Stock Exchange have gathered data confirming its adoption. As per the latter:

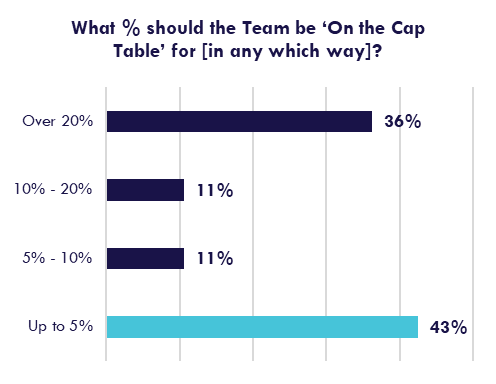

Dutch Data from our Founders Questionnaire

In an effort to raise the curtain on ‘what the market does’, we’ve circulated an online questionnaire amongst friendly Founders and advisors [n=47] and got some insights. And although the ‘N’ here is limited, these founders represent a significant team base and therefore, we consider its outcomes valuable indications.

Although there is chance that respondents understood this question to mean per person, refer to Equity-based plans only or for ‘the Team’ to include founders, follow-up conversations confirm that generally a near 60% majority of the Dutch founders would advise to place over 5% with staff, with many believing firmly in ‘generous dilution’ and indeed >20% Team Ownership.

Where does that leave the founders?

Although it seems that ‘our’ responding Founders are a little more generous than the international population that responded to other published questionnaires, the combined statistics align with Interplay’s Rules of Thumb:

| Initial Equity Target % for Early-Stage Companies: | |

| Founders | 60% – 70% |

| Employee Pool | 10% – 20% |

| Investors & Advisors | 20% |

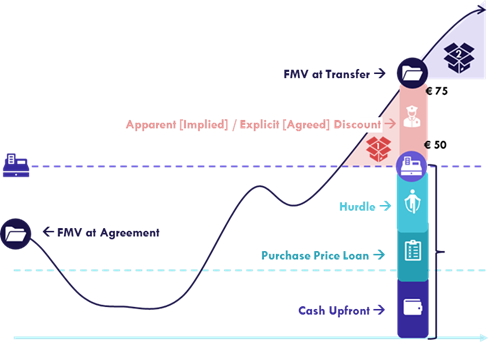

BLOCK 3: HOW? [PURCHASE MECHANISMS]

Purchase Mechanisms shape how and when participants commit financialy, influencing both perceived value and alignment with long-term ownership.

What is a purchase mechanism?

A purchase mechanism defines how someone gets their stake. Not just what they get, but how they get it. It’s the bridge between intention and execution, between “we want you in” and “you’re in.” Whether it’s equity, certificates, options or virtual stock, the purchase mechanism determines:

- Timing (when does the transfer happen?)

- Pricing (what do they pay, if anything?)

- Documentation (what contracts are involved?)

- Tax impact (when is it taxable, and how?)

Common Formats

Cash Buy-In at FMV [go-to]

The participant pays full Fair Market Value for their stake. Clean, simple, and tax-safe. Often used for senior hires or management buy-ins. Can be financed via [a] Personal funds, [b]Vendor loans (e.g. 10-year term, 6% interest) and/or [c] deferred payment schemes.

- Pros: No wage tax, clear ownership

- Cons: Requires liquidity or financing

Discounted Buy-In with Vesting [more complex]

Shares or certificates are granted at a discount, but vest over time. The discount may be taxable as wage in kind, unless structured carefully (e.g. via reverse vesting or dispreference clauses).

- Pros: Aligns with retention

- Cons: Triggers wage tax unless FMV is paid

Dispreference Shares [most complex]

Participants receive shares with a hurdle: they only participate in upside after a certain value is reached. If structured well, the shares are “worthless” at grant and avoid wage tax. Mind the Lucrative Interest threat here though!

- Pros: Real equity, no upfront tax

- Cons: Requires careful drafting to avoid Box 1

Virtual Instruments like SARs or VSUs [when equity isn’t feasible]

In this case, no actual equity is transferred. Perhaps because it turned out too expensive, or because there are restrictions. Instead, participants receive a bonus linked to share value or company performance. No buy-in, no ownership, but still upside.

- Pros: Simple, scalable, no governance impact

- Cons: Taxed as wage, no long-term ownership

Ting Matters

When the transaction happens, affects:

- Taxation (grant vs. vesting vs. exercise)

- Valuation (early = lower FMV)

- Cashflow (can they afford it now?)

Reverse vesting is often used to frontload the taxable moment at a lower value, while still protecting the company via clawback clauses.

Documentation to consider

- Subscription Agreement (for equity)

- SAR or VSU Plan (for virtual instruments)

- Shareholder Agreement (for governance and leaver clauses)

- Loan Agreement (if financing is involved).

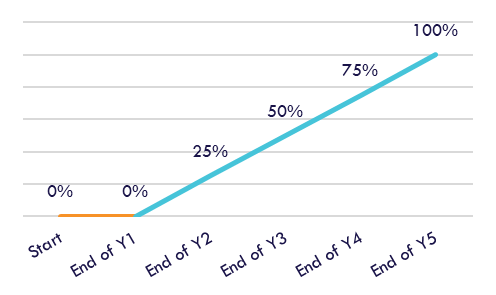

BLOCK 4: HOW FAST? VESTING SCHEMES

A Vesting Scheme is a timed schedule that determines when an empkloyee earns the right to keep their granted equity or benefits, turning potential rewards into real ownership.

Pocketing the Incentive Rights

Although ‘Vesting Scheme’ is a commonly used term, it is challenging to define what it is. In legal terms, rights that have been granted with Vesting conditions are generally understood to have been granted under suspensive of precedent conditions, meaning that the rights are already held by the beneficiary, but do not fully trigger until said conditions are met.

Such conditions can be, for instance, staying with the company for a certain amount of time, obtaining certain patents or meeting a certain Product Readiness Level. Under a Vesting Scheme, the beneficiary to an Incentive Plan may have been granted a certain batch of equity or bonus rights, but these aren’t ‘activated’ until then.

We like to visualize the ‘Vesting’ of such rights as a pre-agreed part of the total batch being ‘toggled on’:

For Tax Purposes: Consider ‘Reverse Vesting’

Vesting Schemes are common practice, but they can have an unexpected effect under Dutch Tax law, which looks at economic ownership over legal ownership. In general, that does not transfer to the beneficiary until the conditions precedent to that end are met, as ‘unvested’ rights would not trigger any rights to proceeds yet; no economic ownership. As a result, a Vesting Scheme can lead to a series of taxable transfer events, which can incur unexpected tax costs of, for instance, Equity Rights are involved, and the company value increases along the ride.

To prevent this, one may consider a Reverse Vesting Scheme under which the rights are fully granted upfront, but certain downside conditions like Bad Leaver clauses lapse with milestones. This would be a ‘transfer under condition of cancellation’ which frontloads the economic transfer rather than postponing

Common Practice: Linear or Incremental Vesting

The most common Vesting Scheme follows an incremental path and is linked to time. For instance: the beneficiary may vest 25% of their batch per year that they stay with the company, or vest 1/48th per month over 4 years:

Cliff Period

Vesting schemes commonly have a ‘Cliff Period’, which is a period in which no rights vest yet. With a one-year Cliff Period, 0% of the rights Vest in Y1, after which the Vesting Scheme is triggered – in this case, a 4-year linear one:

Heavy Tail

In heavily sought after Tech Roles especially, ‘Heavy Tail Vesting’ is on the rise. Under such a scheme, the vesting is concentrated towards the end of the Scheme avoiding quick job hops. Either way, this is just an example meant to emphasize that you can do with Vesting what you want!

BLOCK 5: RUNNING THE SHOP [GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORKS]

Meeting and Voting Right Frameworks in Incentive Plans clarify the extent of participants’ influence in corporate governance.

Ownership and Control

An often-heard notion is that if you were to ask any business owner what would help them progress their company and sleep better at night, it would be for their staff to act more like owners. A logical way for that to happen, of course, is to make them owners of the company by providing them with shares in the business. However, being a shareholder is not for everyone, and there are certain optimums to observe.

For instance: shares come with voting rights and meeting rights and having a decision-making process that involves a crowd of people, can make the company unmanageable and uninvestable. At the same time, beneficiaries who would amass small stakes and especially those at early stages in their careers, may not even want to be part of the ‘capital at risk crew’.

A solution, then, can be to look at other options than shares. Because ‘ownership’ comes in many forms and does not have to be built on full share ownership.

Going Dutch: the STAK or ‘Shareholder Trust’

Many Dutch companies solve this puzzle by implementing a STAK [Stichting Administratiekantoor or Shareholder Trust] which acts as the shareholder and gives the Share Certificate to the beneficiary, separating the ‘legal rights’ from the ‘voting rights’. We like to visualize this as a ticket to the movies which is halved across the dotted line:

The Case for Broader Governance Rights:

Based on broader papers, there’s a case to be made for broader ownership rights:

- Strengthens Ownership MentalityGovernance rights reinforce the perception of true ownership, encouraging participants to think and act like long-term stakeholders.

- Supports Transparency and EngagementAllowing participation in meetings and votes fosters a culture of openness and signals that employee voices matter beyond financial outcomes.

- Aligns with Governance Best PracticesIncluding governance features can enhance alignment with broader corporate governance standards, especially in mature or regulated environments.

- Clarifies Plan Structure and ExpectationsClearly defining governance rights helps distinguish equity-based plans from synthetic or cash-based alternatives, reducing ambiguity for participants.

The Case against Broader Governance Rights:

However:

- Increased Complexity and Legal OverheadGranting governance rights introduces additional legal, administrative, and compliance burdens, especially in multi-jurisdictional or group structures.

- Dilution of Strategic ControlExtending voting rights to a wider group may complicate decision-making and dilute control from core leadership or major shareholders.

- Misalignment with Plan ObjectivesNot all incentive plans aim to replicate full ownership; for many, the goal is financial participation rather than governance involvement.

- Risk of Confusion or MisinterpretationEmployees may conflate symbolic ownership with actual control, leading to unrealistic expectations or misunderstandings about their role in corporate governance.

Getting it Right:

What works for you hinges on who’s involved and on company culture. In an entry-tier plan for a more top-down organization, governance rights are less logical than in a C-Suite plan for a lean startup. Note that there are different ways of implementing ‘ownership’ than through shares. Creating a staff consulting board, for instance, can be just as or even more important for co-governance than having a relatively negligible say in the General Assembly.

Much of this will come down to culture and storytelling as well. Do note that especially for persons in Key Positions, the psychological effect of some form of Ownership elevates a plan way above a ‘simple’ bonus structure so: don’t be afraid to ‘lose control’ – you may just get staff operating like owners in return.

BLOCK 6: SAYING GOODBYE [LEAVER CLAUSES]

Leaver Clauses define what happens to a participant’s unvested or vested rights when they exit the company, protecting the plan’s integryti and aligning outcomes with the nature of the departues.

The Leaver Framework

Because Employee Incentive Plans by their very nature target persons actively involved with the company often through rights that do not necessarily fade out automatically when the involvement of those persons does, it is important to implement a framework that covers what happens in case of such a divorce.

This framework is generally laid out in the Leaver Clause, which defines Bad Leavers, Good Leavers, sometimes also Intermediate Leavers, and what happens to their rights, vested and unvested. It is best explained by simply showing what a concise Leaver Clause could look like:

Example of a Leaver Clause:

In the event that a Participant ceases to be employed by the Company or any of its Affiliates, their status shall be classified as either a Good Leaver or a Bad Leaver, which shall determine the treatment of any vested or unvested rights under this Plan:

Good Leaver

A Participant shall be deemed a Good Leaver if their employment terminates due to:

- Permanent disability or long-term illness;

- Redundancy or termination without cause;

- Retirement with the prior written consent of the Company.

In such cases, the Participant shall retain all vested rights as of the Termination Date. Any unvested rights shall lapse immediately and without compensation, unless otherwise determined by the Board at its sole discretion.

Bad Leaver

A Participant shall be deemed a Bad Leaver if their employment terminates due to:

- Voluntary resignation without the Company’s consent;

- Dismissal for cause, including but not limited to gross misconduct or breach of contract;

- Breach of any post-termination obligations, including non-compete or confidentiality clauses.

In such cases, all vested and unvested rights shall lapse immediately and without compensation.

The determination of leaver status shall be made by the Board in its sole discretion and shall be final and binding.

Choices

There are different ways in which Leaver frameworks can be more or less ‘strict’. For instance: the list of Bad Leaver events can be drafted to include cases in which people leave the company altogether, creating a potentially significant loss of potential when they do. Whether this is reasonable depends, for instance, on whether any upfront payment was required to obtain the rights [like purchased Equities] or whether they ‘simply’ amassed [like Stock Appreciation Rights].

Conversely, they can be more lenient and allow for ‘Accelerated Vesting’ in case of Exit events before an active employee’s Vesting Scheme is fulfilled and have different attitudes towards whether a ‘Good Leaver’ can keep their rights and still share in a later exit or has to present their rights back to the company against a consideration of Fair Market Value at that very moment.

The Fine Line between Protection and Fairness.