This article breaks the ice on the ‘Lucrative Interest’ provision of Dutch Tax law [“Lucratief belangregeling“]. Put briefly, the provision is a broadly scoped anti-abuse rule that intends to use the tax avenue to discourage aggressive practices in management equity remuneration, by taxing equity proceeds that are excessive from a fair market point of view as executive bonus pay rather than dividends or capital gains.

Although the rule was introduced with Private Equity strucures in mind, its wording makes the scope much broader. And such was intended: this fiscal ‘sword of Damocles’ is meant to encourage less adventurous cap table design. As a result, the Lucrative Interest Provision should best always be checked for when cap table events take place. From leveraged management buy-ins to bonafide employee incentive plans.

Let’s take a look at the Provision’s story, its technical workings, and its safe harbors and escape hatches!

The Lucrative Intesest Provision was designed to distinguish between True Dividends and Covert Executive Bonuses.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the Dutch government adopted a legislative package containing a set of tax rule changers. The package was titled ‘the Taxation of Excessive Benefits‘ and aimed to raise additional revenues, of course, but also to affect choices often seen in ‘agressive’ private equity and similar structures, which were deemed to have been a root cause of the collapses that triggered said financial crisis.

As per this legislative package, the Lucrative Interest Provision was introduced: a measure that aims to tax as work income rather than equity income equity proceeds that are significantly linked to manager performance. For instance: Carried Interests,

Basics of Dutch Personal Income Tax, with wages – bonuses included – taxable at 37% to 49%.

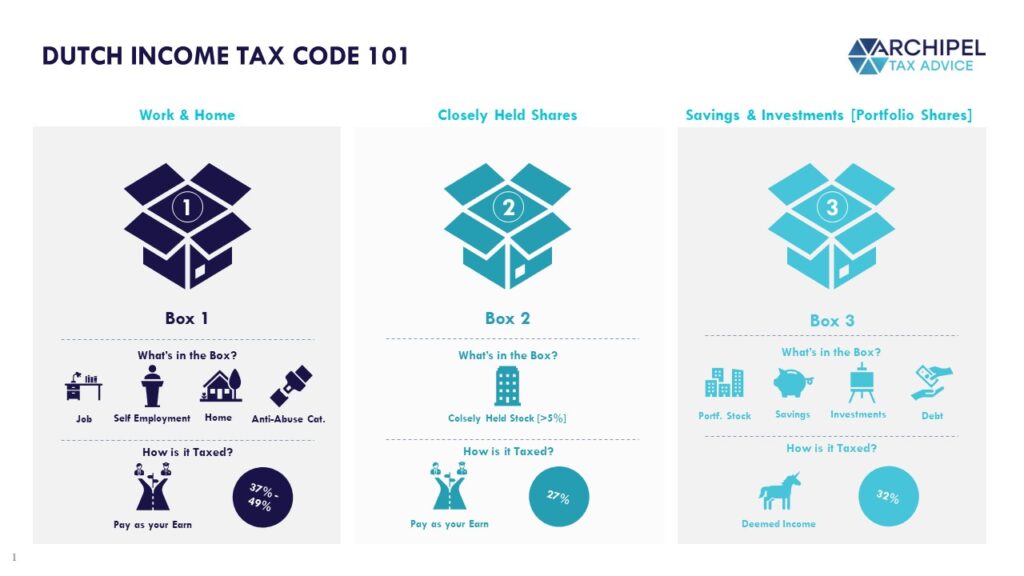

To understand why that matters, we portray the basic workings of the Dutch Personal Income Tax Code, which is set up as a so-called “Analytical Income Tax” meaning that income from different sources is taken into account separately:

The notable dynamics at play here are the following:

- Employment income is taxable in ‘Box 1’ at progressive rates: 37% for income up to € 68k, 49% for income in excess of that. Bonus income is taxable at the marginal rate as it ‘tops up’ the wages already incurred, so for executives this generally means 49% [do note that the bonus is generally deductible for the company];

- Dividends and capital gains, on the other hand, are generally taxable in Box 2 or Box 3:

- The Box 2 regime applies to ‘closely held’ shares [≥5% stakes] and taxes the dividends and capital gains on a remittance basis at a flat rate of 27%, and;

- The Box 3 regime applies to ‘portfolio’ shares [<5% stakes] and follows a bit of a unique scheme the redesign of which is currently a topic of political debate, but which now applies a 6.17% deemed return to the stakes’ Fair Market Value as per Jan 1st, and taxes said return at 32% – regardless of the actual returns (for better of for worse).

- Note that in either case, the dividends are distributions of after-tax profits and are not deductible for the company.

As Equity Proceeds are taxed more favourably than Bonus Payments on a personal level, there is a motive to label performance fees as Equity Payments.

Situations that often give rise to performance-related proceeds are Management Buy-ins, Private Equity Investments [Carried Interest] and the implementation of Employee or C-Level Incentive Plans. In such situations, persons working at the business also become shareholders and a cash-link to company performance can be created either through a KPI-Bonus Scheme or through the cap table.

If we visualize a situation in which a Manager is appointed under an agreement that they receive all proceeds above a 7% Return on Equity with a company Equity Value of € 10.000.000, we can see the following matrix:

| Box 1 Setup | Box 2 Setup | Box 3 Setup | |

| Company Value: | € 10.000.000 | € 10.000.000 | € 10.000.000 |

| Company Profit: | € 1.000.000 | € 1.000.000 | € 1.000.000 |

| Intended for Manager: | € 300.000 | € 300.000 | € 300.000 |

| Manager Bonus: | € 300.000 | € – | € – |

| Manager Dividend: | € – | € 300.000 | € 300.000 |

| Manager Stake: | 0% | 5% | 3% |

| Manager Stake Purchase Price: | € – | € 500.000 | € 300.000 |

| Manager ROI | N/A | 60% | 100% |

| Fund Dividend | € 700.000 | € 700.000 | € 700.000 |

| Fund Stake Purchase Price: | € 10.000.000 | € 9.500.000 | € 9.700.000 |

| Fund ROI: | 7% | 7% | 7% |

| Manager Tax Payable: | € 147.000 | € 81.000 | € 5.923 |

| Manager Net Benefit: | € 153.000 | € 219.000 | € 294.077 |

| Manager Interest ETR: | 49% | 27% | 2% |

| Internal Leverage Manager/Fund: | N/A | 814% | 1386% |

As becomes apparent, from a manager perspective, it would be a ‘Holy Tax Grail’ to succeed in creating a high-return Equity Stake as the carrier of the profits that exceed 7%, as this would reduce their Effective Tax rate from the 49% that applies to bonus wages [Box 1], to the flat 27% that applies to closely held stakes [Box 2], or even the de-facto lump-sum payment on the Stake’s Value that applies to portfolio interests [Box 3].

With the Stake portrayed de-facto creating an in-year ROI of up to 100% against an ETR of no more than 2%, question becomes, of course, whether the value of the stake was actually properly established given the returns potential, but also whether an Equity Package subject to such parameters actually constitutes a Return on Investment at all – as opposed to a Return on Work. As is a Bonus…

Dutch Corporate Law allows for the Creation of Multiple ‘Stock Classes’ and a Side Effect is that certain Stock can become ‘Lucrative’.

To better understand ‘Stock Classes’, we call in the help of Marieke Pols, Corporate Lawyer at the offices of our esteemed friends at De Roos Advocaten.

Marieke, could you portray the Dutch ‘Letter Stock’ system at 10,000ft?

A ‘normal’ Dutch share in a B.V. gives the holder two main rights: the right to vote in a general meeting of shareholders, and the right to receive dividend and sales proceeds. This type of shares is referred to as ordinary shares or common shares.

Dutch law makes it possible to attach or withhold specific rights to/from different types (‘classes’) of shares. A simple example is the distinction between shares with and without voting rights (‘stemrechtloze aandelen’), or between shares with and without profit rights (‘winstrechtloze aandelen’). But a lot of variations are possible: a certain class of share can give the shareholder more financial rights, such as preferred dividend or a preferred ranking in case of a liquidation, or more control, such as the right to appoint one or more directors or to approve/veto certain decisions.

This feature of Dutch law is often used in venture capital and private equity structures. In that case, they are lettered to keep track of the different classes. In venture capital, the financing rounds are even named after the type of shares: in a Series A round, the investors receive A-Shares, in a Series B Round they receive B-Shares et cetera.

Is this unique to the Netherlands?

No, this is a very common phenomenon in other jurisdictions as well.

And within the Letter Stock system, what is a ‘Liquidation Preference’ and how does it work?

Liquidation preference is the term used to describe how proceeds are distributed among the shareholders in case of a liquidation or an exit. Certain classes of shares can rank higher in preference than others, meaning that these preferred shareholders receive part of the proceeds before lower-ranked shareholders get a piece of the pie. Multiple classes of shares can form a ‘liquidation stack’, which is often referred to as a waterfall: proceeds are poured in the top of the waterfall, trickling down from the shareholders with the highest ranking to the ordinary shareholders at the bottom. In exits where the proceeds aren’t as high as the shareholders had hoped – or even worse, bankruptcy -, it may be that proceeds run dry before they reach the ordinary shareholders.

There is a reverse side to this preference: although preferred investors are first in line, the amount they receive is capped. Once they have cashed out their investment, sometimes increased with a pre-agreed dividend (coupon), they aren’t entitled to a share of the remaining proceeds. This cap does not apply to the ordinary shareholders: they share pro rata in whatever is left. In an over-the-moon exit, this can mean that the ordinary shareholders receive a multiple of what the preferred shareholders got. For this reason, investors usually negotiate that they can convert their preferred shares into ordinaries, meaning they forego their preference and share on a pro-rata basis instead.

Founders and managers typically hold ordinary shares. In a scenario where the company goes belly-up, they likely receive few to no liquidation proceeds. But if they – and by extension, the company – do well, they may take a deep dive in the bottom pool of the waterfall.

Thanks Marieke!

The Lucrative Interest Provision in this light, and in more detail.

So, back to the tax matter at hand. As different shareholders can be entitled to receive different proceeds, some shares can produce a much greater Return on Invested Capital than others. But similar constellations can be achieved through loans with a high and/or profit-related interest rate, through high-preference shares, or through other measure with similar results. And especially where management or staff is involved, rather than a third party, this can give rise to the question whether we are indeed looking at an arm’s length return on equity, or -in fact- at a rebranded bonus.

Enter: the Lucrative Interest Provision, that aims to capture constellations that are subject to conditions that effectively give rise to the question whether or not would-be bonus payments have been engineered to present as Equity or other Financial Returns, when in essence, well, they aren’t.

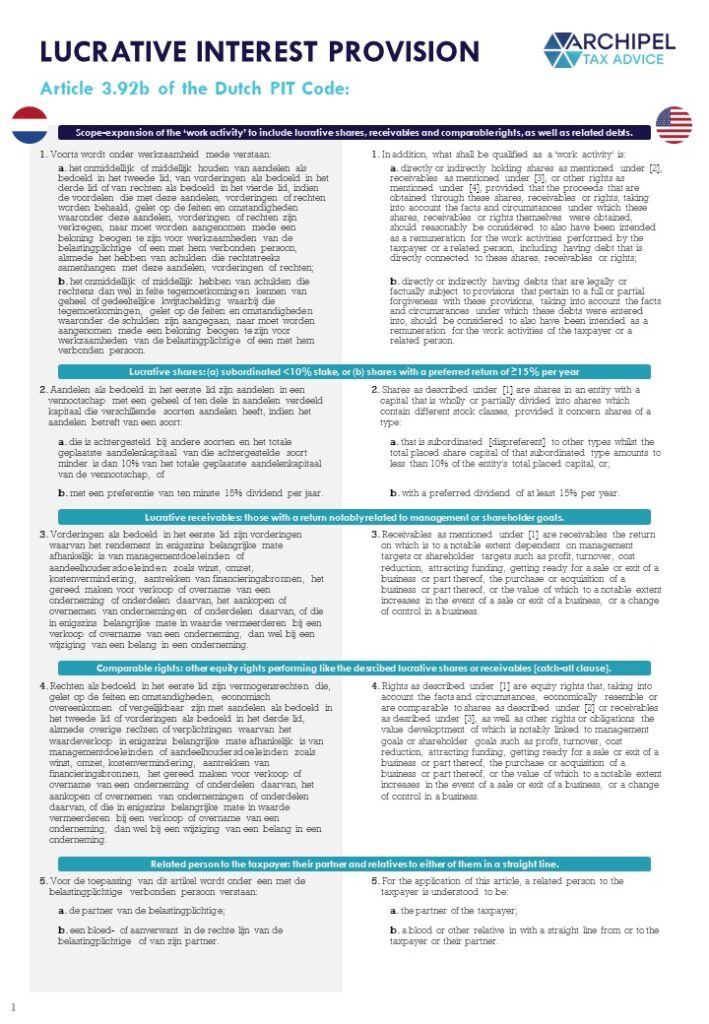

What does the Lucrative Interest Provision look like?

In order to help the legal and finance folks that may be checking in to this article grasp the paremeters, we place a ‘guided translation’ of the legal Provision:

Our tl;dr of this provision: the payments on any financial instrument that is engineered such that its individual returns are closely linked to specific management or shareholder goals – and that therefore performs very similar to a bonus – are at risk of being requalified from equity income to work income.

A tangible example is a portfolio stake that has been extended to management and that contains a liquidation preference resulting in a much higher pay-out per share upon exit than what will be distributed on the regular shares.

What’s the Idea?

In essence, the provision aims to tax ‘lucrative’ capital titles, containing specific provisions that create a situation in which the potential returns far outweigh the capital at risk such that it is unlikely that the title would ever be put on offer in the open market.

The Provision’s parliamentary history clarifies that the ‘notable link‘ to management goals basically means that the covered instruments are those with non-general conditions and a lucrative element.

The link with management goals is ‘notable’ if these are at least a 15%-factor in determining the returns on the instrument at hand [ref. the parliamentary history of the provision], and is included in the shares and receivables categories, as well as (the second part of) the catch-all clause that is the fourth paragraph, which has been stated to cover at least the following examples:

- Leaver clauses with a sellback-provision under which the transfer price of stock is importantly linked to the conditions of terminataion and can end up way above Fair Market Value;

- Ratchets or Reverse Ratchets under which, for instance, later stock transfer are importantly linked to management goals, or;

- Share purchase loans financed at the bank against a warranty issued by the PE and subject to forfeiting conditions linked to the share price. These are covered in the second part of the first paragraph as well.

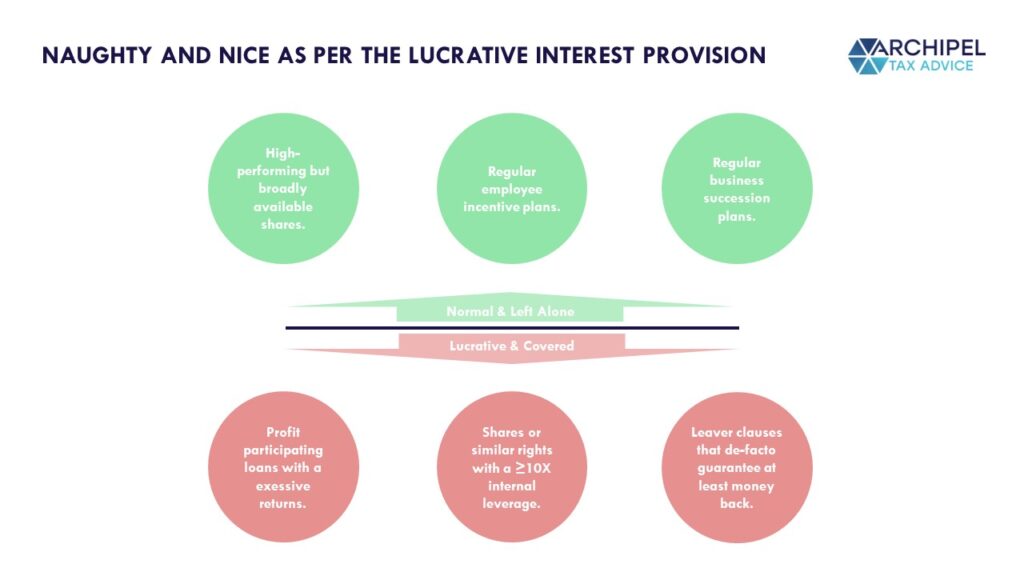

Sounds like the Provision may contain some overkill!

Yes, and that is exactly the design: the provision is intended to have an unclear and broad scope, and it is ironically aimed at not being triggered as persons would avoid ‘lucrative’ arrangements. If the scope were to be established very precisely, it would become equally precisely possible to plan ‘around’ the provision. As per the legislator:

It is not possible to thoroughly specify the distinction between a regular -but high- return on the one hand and an excessive return on the other, as this could lead to avoiding behaviors. After all, if such a distinction were to be precisely specified in the law, it would be relatively easy to aim for the boundaries of such a defined normal return. Also, it should be kept in mind that situations involving carried interests and similar remunerations are often very complex in their setup. For that reason too, it is not feasibly to create a proper, thorough and executable definition of a normal or excessve return, which the proposal should cover. Ultimately, it all comes down the facts and circumstances of a concrete situation that needs to be analyzed. Naturally, the legality of such an analysis by the Inspector can always be brought in front of a judge.

The Legislator’s official minutes of the provision’s design process.

What can I do to prevent being captured by the provision?

The annoying answer, of course, is to *not* implement a constellation that fits the description of the Luctrative Interest provision:

As the provision’s wording is so vague, it’s scope has been shaped by extensive case law, policy documents and decrees. Notable sources include the parlimanetary records and the Dutch Tax Authorities’ note on Private Equity and Taxes. From these, we learn that – for instance – ‘regular’ employee participation plans should not be covered even though their returns inevitably have a link to ‘management goals’ that these employees may influence and although they may not become widely available. At the same time, we learn that leaver clauses that de-facto guarantee at least money back ‘switches’ such plans into Lucrative Interests.

Also, it is notable that the test of “Lucrativity” is implicitly included in the second paragraph’s <10:90 ratio criterion (which also happens to apply more broadly to the fourth paragraph’s first category of ‘similar rights’), which should be tested continuously, so not only at the moment of issuance/grant. Whereas, contrarily, the subjective ‘remuneration for work’ criterion of the first paragraph’s first part is tested only at the issuance/grant moment. So: the lucrativity does not actually depend on how the waterfall would materialize. However, some may argue that the shares’ Fair Market Value was not properly established upon issuance if a ‘Lucrative’ leverage then also materializes, perhaps triggering back-wage taxes on the difference between the actual transfer price and the adjusted FMV at that moment, reducing the leverage on the invested capital and perhaps “de-lucrativizing” the stake… Such are ramblings of these tax guys at least.

Fair Market Value and the Discounted Cashflow Method.

For a read on establishing the Fair Market Value of a stake for Tax Purposes and, essentialy, a crash-course on the Dicounted Cashflow Method, we refer to this earlier blog post:

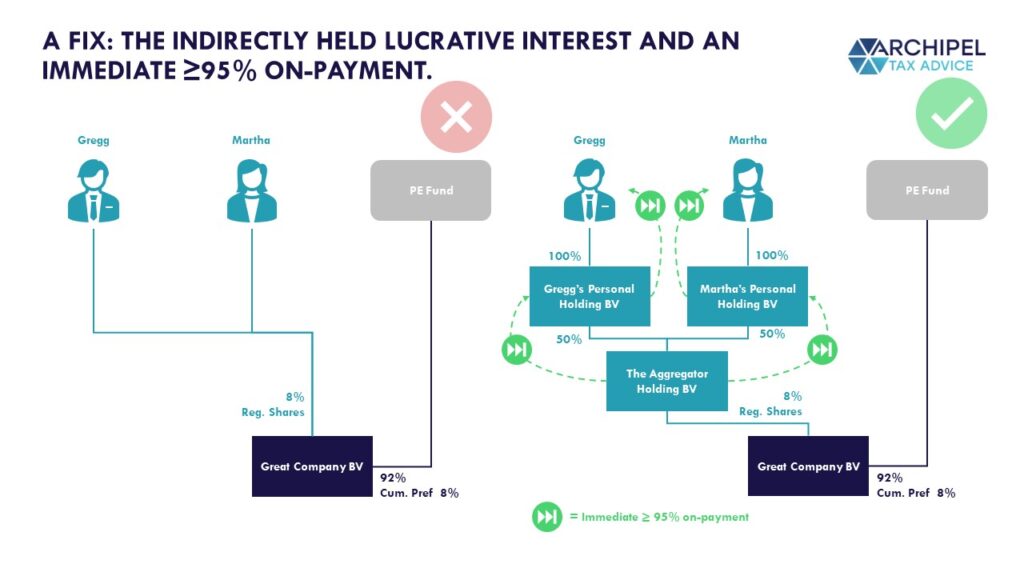

What can I do if my interest is Lucrative? The ‘Escape Hatch’ of the Indirectly Held Lucrative Interest with a 95% immediate on-payment.

If, at any point, it appears uphill to argue that a management-link exists on an exclusive package, it can be advisable to ‘accept’ the Lucrative status of the interest rather than adjust all sorts of commercial contracting in an effort to circumvent it.

The Dutch legislator has implemented an Escape Hatch in article 3.95b of the Dutch Personal Income Tax Act [fifth paragraph]:

If the taxpayer so chooses, the in-year proceeds received on account of an indirectly held [Lucrative interest] are not accounted for as income from work as long as in that same year, an amount equal to at least 95% of said (net) proceeds is reflected and received as income from closely held shareholdings.

The escape hatch.

In the example visualized above, Gregg and Martha each own 4% of the regular shares in a leveraged PE-structure that we mark as lucrative. In the Base Case, Gregg and Martha would be taxed at max. 49,5% Personal Income Tax for any proceeds on these shares, while the payment is *not* deductible for the company. By restructuring their shareholdings such that they hold the stake ‘indirectly’ through their personal holding entities and by always paying forward at least 95% of the stakes’ proceeds within the calendar year, they avoid the 49,5% tax rate of Box 1 and instead secure access to Box 2; income from closely held shareholdings taxed at 26,9%.

The cumulative tax rate on these proceeds (including the operational business profits), considering that for the company, they remain a non-deductible distribution of dividends, is 25,8% Corporate Income Tax + [[100,0%-25,8%] * 26,9%] Personal Income Taxes, adding up to approx. 45,8%, as apposed to the cumulative 62,5% of the Base Case scenario. Note that the intermediate holding entity ‘The Aggregator’ is a necessary step to secure the Participation Exemption at a corporate level, so as to avoid injecting an additional CIT-taxable layer. The Participation Exemption applies -in short- to min. 5% stakes held by entities in other ‘realistically taxed’ entities.

With this escape, the proceeds on Lucrative interests are taxed as regular income from closely held shares, but the owner does not get to defer Personal Income Taxes on the proceeds by retaining the earnings within their holding entities.

What’s the rationale?

By structuring a Lucrative interest such that it is owned by a holding entity, the taxpayer could effectively avoid incuring any ‘income’ from such a stake by retaining the income at that level. In addition to adopting a set of anti-deferral rules like those that ‘see through’ the interposed holding entity for Personal Income Tax purposes, the legislator adopted this ‘escape hatch’ for such interests the earnings of which are *not* retained by the owner.

The Lucrative Interest Provision may be in play. What should I do?

The steps I’d recommend:

- Establish the workings of the Interest and calculate whether there is a realistic downside risk and a non-excessive pay-out potential [max. 10 to 1];

- Establish if the shares are linked to management or broadly and externally available – perhaps there is a ‘Legal Escape‘;

- If the stake indeed seems Lucrative and exclusive, there might be an ‘Economic Escape’; see if you can adjust the conditions to de-lucrativize the stake, for instance by adjusting clauses or making the buy-in [downside risk] more reflective of the upside potential, in order to de-check the subjective ‘remuneration for work’ criterion (even though, weirdly enough, according to Parliamentary History paying the Fair Market Value does not preclude that this criterion is met);

- If these adjustments surpass the adjustments you are willing to make from a business or personal finance perespective, see if you can restructure such that the 95% Escape Hatch can be applied, all the while taking into account the Participation Exemption criteria.

In any case, I would recommend obtaining a Ruling with the Dutch Tax Authorities that covers the Lucrativeness – or the lack thereof – of the involved Interest, to ensure certainty. The broadness of the scope indeed makes the Lucrative Interest provision one that always maybe applies, yet – and this is the good news – equally always maybe not!