In this read, we compare the OECD Model Tax Treaty to the UN Model Tax Treaty after the UN adopted a historic resolution to take the driver seat in the global tax debate and thank the OECD for its efforts. Buckle up, it’s a long one. For tax and history buffs alike.

Setting the Arena: International Economics and International Tax

In an ever globalizing world economy, business increasingly takes place across borders. For tax purposes, this adds a layer of complexity; imagine that a company has its HQ in State A and makes profits on a construction project in State B. Said company’s home state ‘A’ may want to tax the project gains because its tax code covers the profits of its resident businesses, whereas the source state B may equally want to tax the project gains because its tax code covers the profits physically arising within its borders. In such situations, Bilateral Tax Treaties set the Rules of Engagement and regulate who gets to tax what [or more accurately said: who doesn’t get to tax what].

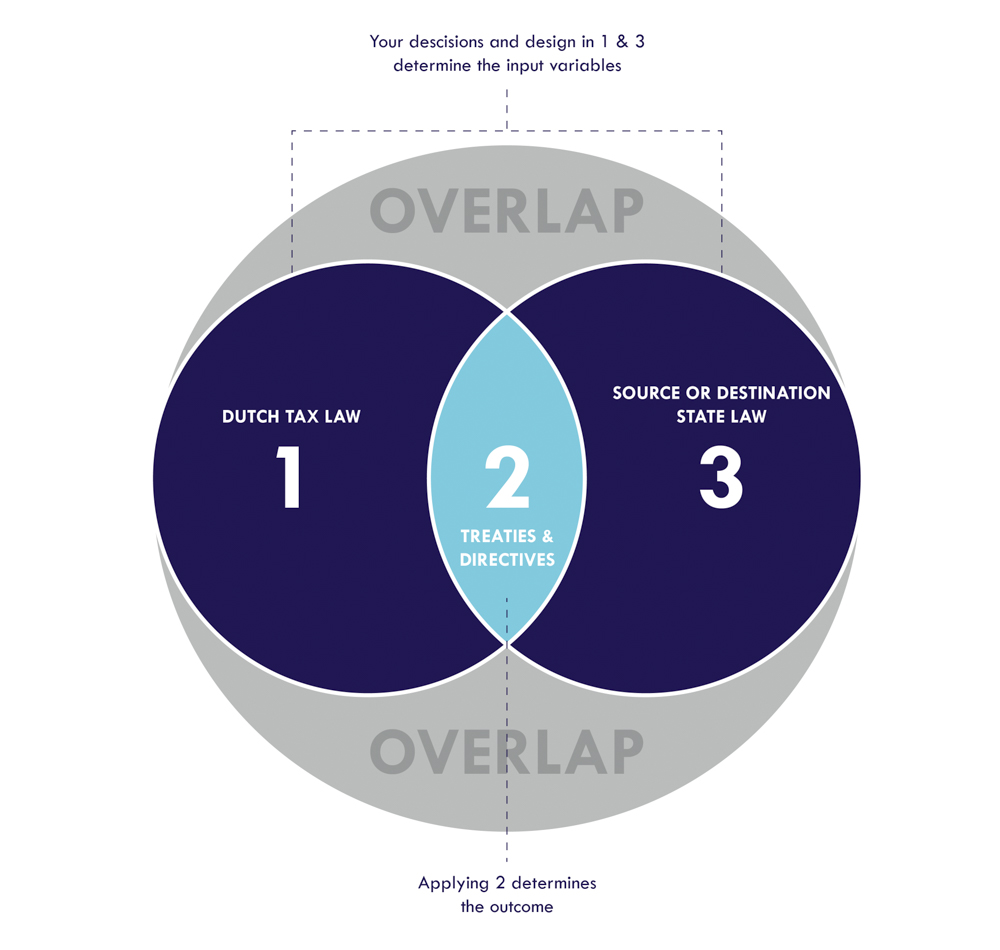

We always like to visualize this as a Venn diagram, that portrays the classic ‘step plan’ to establishing cross border tax competencies: what does State A ‘want’ to tax [based on its domestic tax code], what does State B ‘want’ to tax, and how does an applicable Treaty referee where these two ‘wants’ overlap?

What is a Tax Treaty and what does it Look Like?

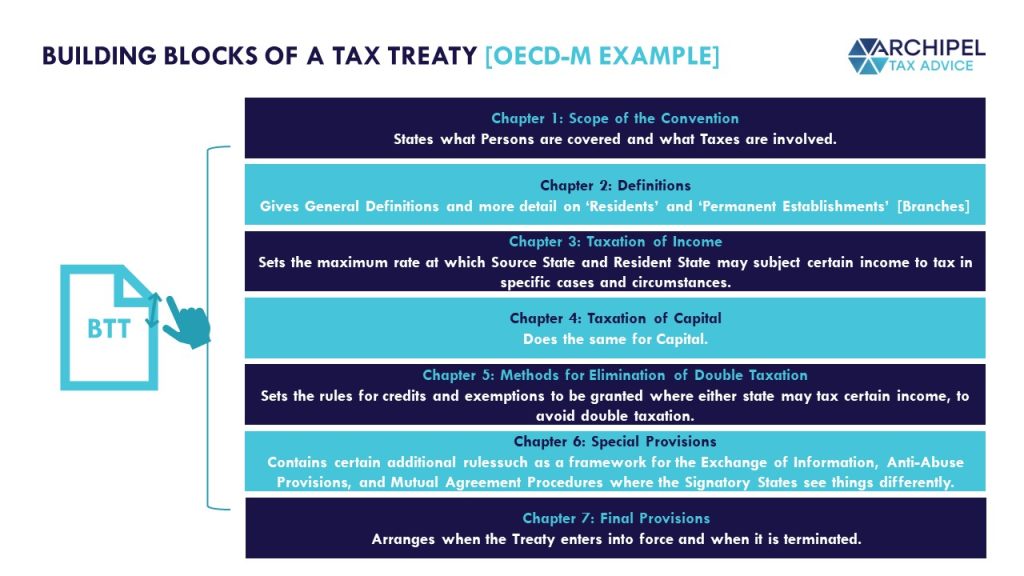

A Bilateral Tax Treaty [BTT] is a Treaty concluded between two states that tops both states’ domestic laws in ‘legal seniority’ and, as such, sets the boundaries for both states’ taxing rights in the interactions with and between each others’ residents.

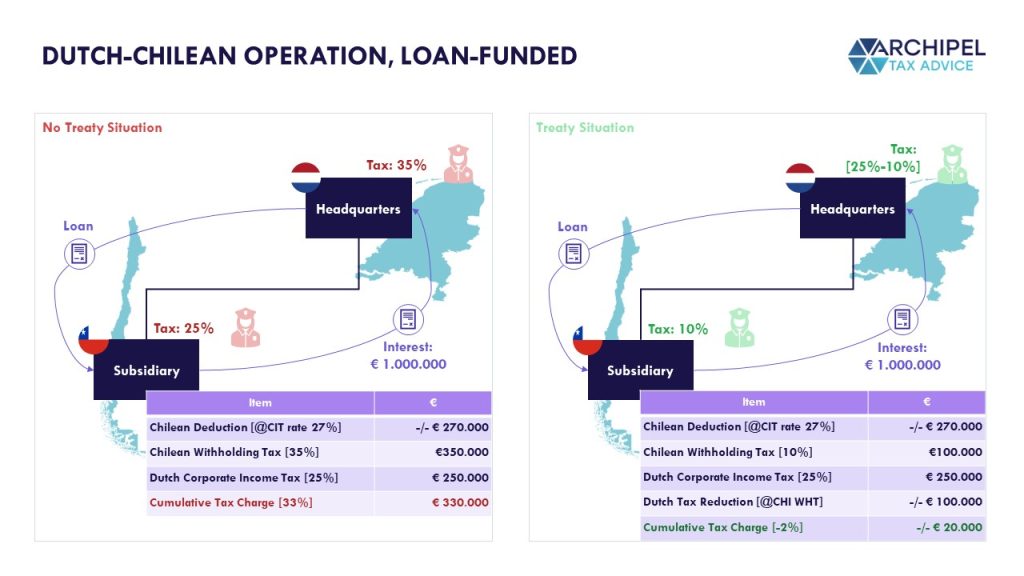

An example of how this would work: imagine that the Dutch company Scallop Energies sets up a subsidiary in Chile, where it sells hydrogen. The Dutch HQ may use cash at hand to provide a loan to the Chilean subsidiary with which it finances the building of its hydrogen station. The arm’s length interest due annually is € 1.000.000.

Logically assuming that Callop’s HQ qualifies as a Dutch Resident for Tax Purposes and the Hydrogen Subsidiary as a Chilean one [generally meaning they are both substantive enough, i.e. non-letterbox, to have access to the Treaty], the newly concluded Dutch-Chilean BTT would come to cover the Interest Payment.

Based on Chilean domestic law, we assume that the interest payment made to the Dutch HQ is subject to the 35% withholding tax that applies to interest payments made to non-Chilean residents. The interest payment is equally included in the Dutch taxable base, however, as it is included in the Dutch HQ’s taxable income. Therefore, a risk of double taxation arises. In other words: both states ‘want’ to tax the same payment.

Enter the Dutch-Chilean Tax Treaty. Its Article 11.2.b states that the tax imposed by the source state, Chile in this case, shall not exceed 10%. And article 23.2.b states that The Netherlands is to allow a deduction from its tax charge equal to the tax withheld in Chile [the double tax avoidance mechanism].

The visual below shows that the implementation of the BTT reduces the tax leakage on the group funding of the subsidiary from 33% to an actual -2% due to positive arbitrage on the loan [interest deducted against a higher CIT rate than is applicable to the pick-up]:

A studies by Fabian Barthel [at al] shows that the conclusion of a BTT leads to -on average- a 30% increase in mutual investment flows, and the above underlines how such a treaty drastically increases an investment case. Also, the above shows that the thresholds set by the Tax Treaty effectively ‘allocate’ the taxing rights between the involved states. Simultaneously, this graphic shows why Tax Treaties also need some anti-abuse provisions; it is easy to see why a company with Chilean ambitions but headquartered in a state without a Chilean treaty would want to ‘interpose’ a Dutch entity [especially when the HQ-state does have a treaty with the Netherlands] to capture better treatment. That shows that aside from rates, the treaties also need to ring-fence a group of covered persons and parameters for abuse, etc. But: first thing first.

How are Tax Treaties Negotiated and Concluded?

Delegations of the two involved states arrange for a series of meetings and each have their own goals. For instance: some countries may want to increase Foreign Investments so as to increase job opportunities or innovation within their borders, and offer low or no withholding tax rates as a result. At the same time, states may see withholding taxes as a means to fund their national programs, and may opt for higher rates to shift the financing burden to foreign investors.

Either way, many countries have a ‘National Model Treaty’ or a ‘Treaty Policy’ that gives the delegates the parameters of the national government’s goals in treaty negotiations. In order to prevent having to ‘reinvent the wheel’ every time and to keep international tax law somewhat coherent, the delegates usually use a ‘Model treaty’ as a template and guideline for the Tax Treaty negotiations. And what Model they use, already influences the shape of the negotiation arena, and therefore the outcome. So let’s zoom out and rewind, and see where these templates originate and what are the delicate politics and histories behind them.

A Brief History of Tax Treaties

For a concise history of the rise of the phenomenon, we refer to Brian Arnolds’ paper An Introduction to Tax Treaties:

Model tax treaties have a long history, beginning with early diplomatic treaties of the

Brian J. Arnolds of the Canadian Tax Foundation, for the UN.

nineteenth century. The limited objective of these treaties was to ensure that diplomats of one country working in another country would not be discriminated against. These diplomatic treaties were extended to cover income taxation once it became significant in the early part of the twentieth century. After the First World War, the League of Nations commenced work on the development of model tax conventions, including models dealing with income and capital tax issues. This work culminated in Model Conventions in 1943 and 1946. These Model Conventions were not unanimously accepted, and the work of creating an acceptable model treaty was taken over by the OECD and, a few years later, the United Nations.

The Reason for Tax Treaties

So Bilateral Tax Treaties [BTTs] originated as a means to warranty a tax treatment of diplomats working abroad equal to the treatment of locals. But as time progressed and business, too, increasingly globalized, the scope of BTTs expanded to the private sector. Tax Treaties were seen and have since proven to remove obstacles for international business, which added to economic ties and intertwinedness between states. To illustrate that: Joseph Grieco analyzed that the industrialized countries reduced their average tariffs after World War II from about 40% in 1946 to about 5% at the end of the 1990s, which lead to total real exports in 1997 amounting to roughly 14 times that in 1950.

Now apart from creating better opportunities for economic specialization and growth, as a sign of the times, this intertwinedness also became sought after for its contribution to world peace; after the Second World War, BTTs’ popularity grew as classic beliefs we re-embraced that an increased economic interdependence leads to a decreased likelyhood of military conflict. For a good read on this, we refer to Joseph Grieco’s paper The International Political Economy Since World War II.

So long story short: BTTs are a means to increased business and peace.

Model Treaties and the League of Nations’ Original Document

These BTTs are individual documents, but they follow a certain template. And this phenomenon has a history of its own. In order to better understand it, we best start with ‘Mother of all Tax Treaties’; a first draft created by the League of Nations, the predecessor of the current-day United Nations that was founded in 1920 as per the Paris Agreement that ended the First World War. Under its stewardship, more specifically its ‘ General Meeting of Government Experts on Double Taxation

and Tax Evasion, the 1928 League of Nations Model Treaty was drafted and issued.

The mission stated in its article 1: The present Convention is designed to prevent double taxation in the sphere of direct impersonal or personal taxes, in the case of the taxpayers of the Contracting Parties, whether nationals or otherwise.

The Divergence into Two Drafts – Mexico City vs. London:

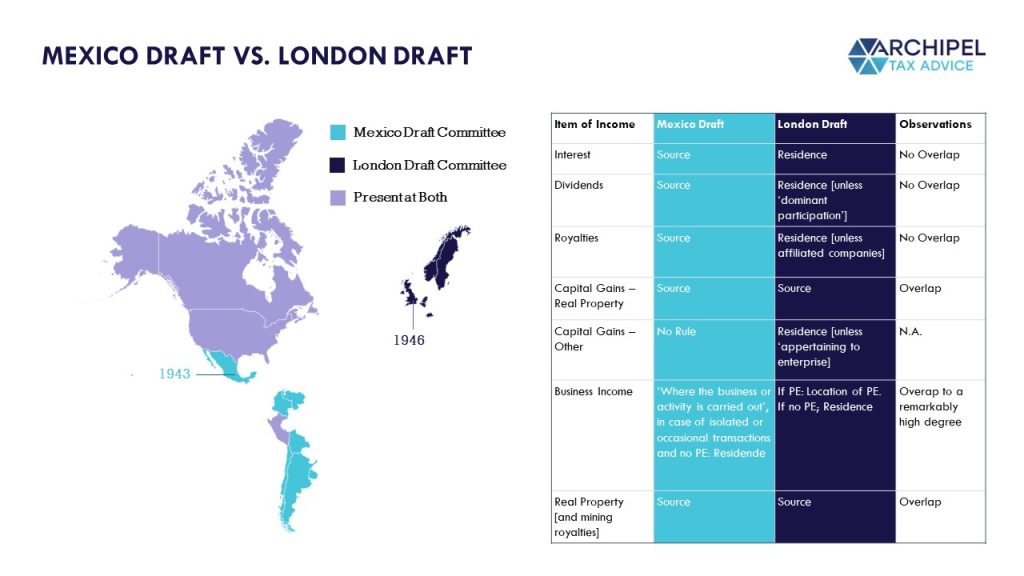

The initial draft was not unanimously accepted as a result of which a Fiscal Committee was formed by the League in 1928. This Committee issued a new Model Treaty working draft in 1935 which equally received pushback, after which the Fiscal Committee proposed to redraft a Model Treaty. And so it was agreed on a 1940 convention in Archipel’s HQ Town of The Hague, that the process of a new draft should commence.

But then: war ensued. Nonetheless, the part of the League that was less preoccupied at the time, convened in Mexico City in 1943 and issued a Draft Model Treaty known as ‘The Mexico Draft’. The member nations that sent their representatives to the committee meeting were mostly Latin American, and generally comprised ‘capital importing’ states. The Mexico Draft, therefore, appeared to gravitate towards destination state taxation.

Quickly after the Second World War ended, the entangled liberal capitalist states of Western Europe reconvened the League’s Fiscal Committee and set out to regain influence on these developments that took place during the war during a 1946 convention in London. This resulted in the 1946 ‘London Draft’ which more heavily reflects the ‘capital exporting’ states and therefore gravitates to resident state taxation. [For further historic reading, we recommend this paper by the United Nations’ Taxation tank.]

After these two ‘legs’ of the League drafted their versions, it proved difficult to reach consensus yet again. The League made one last attempt, and the preamble to a synthesized version of the Mexico and London Drafts issued by the League of Nations in an attempt to converge the schools of thought states the following:

“This work of revision and codification was undertaken by a Sub-Committee which met at The Hague in April 1940, and was continued by two Regional Tax Conferences which were held under the auspices of the Fiscal Committee, in Mexico City in June 1940 and July 1943.

The Committee has now studied the result of this work. It wishes to express its agreement with most of the conclusions which were reached by the experts who met in Mexico City in 1943 and is of the opinion that the Model Conventions prepared by those experts represent a definite improvement on the 1928 Model Conventions. Nevertheless, since the membership of the Mexico City and London meetings differed considerably, it is natural that the participants in the London meeting held, on various points, different views from those which inspired the Model Conventions prepared in Mexico. The general structure of the Model Conventions drafted at the present session is similar to that of the Mexico models. A certain number of changes have been made in the wording, and some articles have been suppressed because they contained provisions already implied in other clauses. On other points, new articles have been inserted to make use of certain innovations contained in conventions, such as those between the United Kingdom and the United States, concluded since the 1943 meeting. Virtually, the only clauses where there is an effective divergence between the views of the 1943 Mexico meeting and those of the 1946 London meeting are those relating to the taxation of interest, dividends, royalties, annuities and pensions. The Committee is aware of the fact that the provisions contained in the 1943 Model Conventions may appear more attractive to some States—in Latin America for instance—than those which it has agreed during its present session. The two texts are therefore given on opposite pages in Annex A. The Model Conventions, as they now stand, can afford guidance to negotiators of tax treaties. The Committee thinks that the work done both in Mexico and in London could be usefully reviewed and developed by a balanced group of tax administrators and experts from both capital-importing and capital-exporting countries and from economically-advanced and less-advanced countries, when the League work on international tax problems is taken over by the United Nations.”

And so the Mexico and London Drafts were never consolidated again. Fast forward and the League of Nations disbanded in 1946 after which it was succeeded by the United Nations.

After the War: the United Nations [UN] and the Organization for European Economic Cooperation [OEEC] as Tax Treaty Modelists

An important event in the history of Model Treaties is the incorporation of the OEEC. In the wording of the OECD: “the forerunner of the OECD was the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), which was formed to administer American and Canadian aid under the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe after World War II.”

This Marshall Plan was a recovery plan instated mainly by the United States, aimed at supercharging Europe’s economic recovery post Second World War. By facilitating trade and prosperity, this plan had a political angle too, offering an important counterweight to the then USSR’s communist ambitions. It is no surprise, then, that the OEEC had an outspokenly pro-trade DNA.

As for the treaties: in the 1950’s, the two drafts lived their lives and little additional work was performed. But: in 1956, the OEEC established a Fiscal Committee which picked back up the work previously performed by the London Committee, in an effort to further economic ties between nations [and, with that, warranty peace]. A little later, the OEEC rolled over into today’s Organization for Economic Coorperation and Development or ‘OECD‘, which spans past just Europe and actively took on a fiscal role, and as such, began drafting its first Model Treaty as per 1963. The United Nations, meanwhile, had a back seat and it wasn’t until 1968, its own ad-hoc group of fiscal experts was formed.

Fast forward and the installations of these two platforms resulted in equally two first Model Treaties being published approximately a decade later: the new OECD Model Treaty [‘OECD-M’] in 1977 and the UN Model Treaty [‘UN-M’] in 1980.

The theme of the United Nations’ forming seminars and the title of the concocted UN-M evidence a developmental leaning: the “UN Model Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries”.

The OECD, meanwhile, titled its Model Treaty “OECD Model Double Taxation on Income and on Capital”. The OECD itelf has since issued wording on this topic as follows:

“In both the 1963 and the 1977 Model Convention, the title of the Model Convention included a reference to the elimination of douvle taxation. In recognition of the fact that the Model Convention does not deal exclusively with the elimination of double taxation but also addresses other issues, such as the prevention of tax evasion and avoidance as well as non-discrimination, it was decided, in 1992, to use a shorter title which did not include this reference.”

So: the historic image here is that the UN-M builds on the 1943 Mexico Draft that is floated more by capital importing states and favors source state taxation, whereas the OECD-M builds on the 1946 London draft is floated more by capital exporting states and favors resident state taxation.

For more backgournd on this, we refer to Paul Lennards slides for an IMF gathering on this topic.

The OECD Chapter in International Tax

The OECD’s Rise to Dominance in the Tax Field and the OECD-M’s position as the Golden Standard

International taxation can call for an international custodian as it can be difficult for states, that are ultimately in a form competition for business and talent, to agree on certain minimum thresholds and harmonizations. By appointing or accepting an international platform and referee, the pressure on national governments to undercut their competitors can be aleviated.

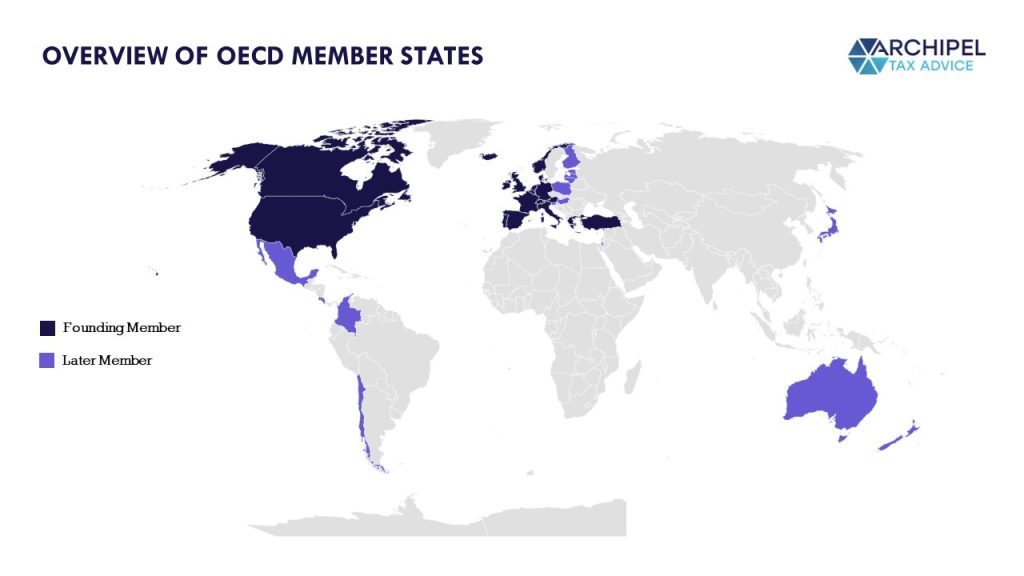

The OECD as an international organization has de-facto been appointed this position by its member states, currently the following nations:

This visual shows that the OECD’s center of gravity lies with ‘the Western World’. These 38 member states’ combined GDP equals to nearly 50% of Global GDP, down from over 60% in 2005 due to the economic emergence of developing and non-member countries. The OECD is often a podium for expert groups sent by its member states to have guided discussions and for their delegates to reach common stances. Combining the carrying power of such a platform’s stances with the purchasing power of its members, it is no surprise that the OECD’s Tax Models [plural because the templates are updated every now and then] have unofficially grown into the dominant template.

To illustrate this, we take data from a paper by Elliot Ash and Omar Marin’s 2019 paper for NYU titled “The Making of International Tax Law: Empirical Evidence from Natural Language Processing”. It shows that there are currently over 3.000 BTTs in place. On average, they show most similarity with an OECD-M at nearly 70% [and second with a UN-M and third with a US-M].

The Legal Status of the OECD’s ‘Stuff’

With the OECD-M often being the template that negotiating parties base their treaties on, and many member states and even non-member states proviging input for new drafts, the legal status of the OECD’s issues remain topic for debate amongst scholars, but it is agreed that its standing has been ever increasing, keeping tread with the adoption of OECD templates and standards.

As the realm of ‘legal theory’ underlying the legality and legal seniority of these documents is near endless, we quote a rather concise paragraph by Diego Mejía-Lemos for Leiden University’s Law Blog:

“The scholarly analyses of the nature of the OECD Commentaries often rely on conceptual frameworks distinguishing between ‘binding’ and ‘non-binding’, and the ‘no man’s land’ in between […], political and legal commitments […], and ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ law […]. The prevailing position among scholars and in judicial practice is that the OECD Model Tax Convention, and, a fortiori, the OECD Commentaries, are not legally binding per se (eg AG Opinion, C-119/16 (2018), para 50). [However] it has been claimed that the OECD Commentaries may become binding for OECD Member states whose DTTs incorporate OECD Model Convention provisions: those legal consequences would extend to any such DTT by virtue of acquiescence or estoppel “

This means that based on lengthy scholarly analyses, the OECD’s documents can shape legal consequences as ‘soft law’ especially when they are accepted or even not-rejected by parties involved in their making. In some cases, however, specific mention of OECD documents can be made in domestic legislative processes leaving little question as to their validity. An example is the Dutch Transfer Pricing Decree, that specifically states that the Transfer Pricing provision in the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Code is a codification of the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines which are in turn an implementation of the OECD-M’s article 9 on Business Profits.

The OECD itself is rather clear on this. Its own glossary shows the following definition for soft law:

“Soft Law’

Definition

Co-operation based on instruments that are not legally binding, or whose binding force is somewhat ‘weaker’ than that of traditional law, such as codes of conduct, guidelines, roadmaps and peer reviews.

Examples

OECD set of Guidelines and Principles, combined with peer review mechanisms.”

Concerns about the OECD’s Soft Law status and its captaincy in International Tax templating and reform

The OECD being a dominant force in international template-setting and the de-facto ‘near binding status’ of their writings, can lead to concerns. For instance, the OECD is not a directly elected institution and attributing it with legislative powers would be difficult to place within the principle of ‘no taxation without representation’. And: the majority of countries and -now adays- over half the world’s purchasing power is not represented in the platform.

Note that the scope of the OECD’s work spans far beyond just the OECD-M. For instance: the OECD launched and captains the international project titled ‘Anti Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ which aims to harmonize minimum standards and creates a method for project supporting states [not necessarily members] to take joint action against states not meeting them. A most recent stone to that pyramid is the OECD’s Pillar One / Pillar Two-approach, which includes a global minimum Corporate Income Tax rate [of 15%]. As per the OECD:

“As of 4 November 2021, over 135 countries and jurisdictions joined a new two-pillar plan to reform international taxation rules and ensure that multinational enterprises pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate“

And although the stated goal is difficult to oppose, elements of it do take away sovereign states’ control over their fiscal instrument as a means to shape their societies and economies. This project is heavily driven by the Western World as their statutory CIT rate -save a few exceptions- is already structurally above that 15%. Long story short: the OECD’s work is aimed mostly at streamlining international trade and creating a platform for communal action against avoidance openings where tax competition could inhibit a fix, but as their efforts become increasingly harmonizing in effect, the narrow institution increasingly ‘threads the needle’ on balancing with tax sovereignty [we refer to this interesting read by Maximilian Frank for The Internationalist].

“The OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting initiative is an important step in furthering the cooperation between states to tackle the harms of tax competition and the aggressive tax planning of MNCs it facilitates. But while the OECD’s ostensible concern with effective tax sovereignty is laudable, I [state] that the structure of proposals insufficiently addresses the injustice of current inequality in effective tax sovereignty. I [point] out that, practical concerns aside, the principle of economic allegiance on its own does not protect states in their quest for FDI from tax competition (‘real’ tax competition) that may undermine their capacity to engage in redistributive programmes. [I] accordingly [suggest] that it is possible to establish a greater consensus among internationalists and cosmopolitans about the necessary reforms of the international taxation regime.“

So building on the ‘taxation without representation’-idea; the OECD means well, but many non-OECD states remain unsufficiently heard on the platform for it to implement globe-spanning ideas, especially where would be given soft law status.

The Re-emergence of the United Nations as a Tax Institute: United Nations Resolution

After a decade of OECD rapid-fire proposals with increasingly harmonizing goals, counter pressure mounted. And on November 23rd, 2022, this lead to a historic and African-nations-championed resolution being unanimously adopted by the United Nations’ General Assembly. The core of this Resolution A/C.2/77/L.11/Rev.1:

“The General Assembly […] Decides to begin intergovernmental discussions in New York at United

Nations Headquarters on ways to strengthen the inclusiveness and effectiveness of international tax cooperation through the evaluation of additional options, including the possibility of developing an international tax cooperation framework or instrument that is developed and agreed upon through a United Nations intergovernmental process, taking into full consideration existing international and

multilateral arrangements“

“In a diplomatic win for African states, the United Nations has agreed to lay the groundwork for the creation of a new system of international tax cooperation.

The U.N. approved a resolution today to begin talks on establishing a new global tax system that could reign in corporate tax dodging and curb money laundering around the world.

The resolution was submitted for consideration by Nigeria on behalf of the 54-member African group of states, who are hoping for a greater say in global tax policy — something that has traditionally been the domain of a small group of wealthy nations via the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

“This is a historic win for the tax justice and the broader economic justice movement and a big step forward to combat illicit financial flows and tax abuses,” Global Alliance for Tax Justice’s executive coordinator Dereje Alemayehu said in a statement.

Shifting power from the OECD is paramount to end the exploitation and plunder of developing countries.”

Watch a replay of the Assembly Meeting here.

What does this mean for Tax Treaties?

Although many OECD Members supported the resolution ‘with reservations’ [see score card here], it is clear that the African Nations, not represented in the OECD, made a succesful ploy that international tax policy should be built on a more international platform.

As summarized by the Tax Justice Network:

“The UN General Assembly adopted on Wednesday 23 November 2022 by unanimous consensus a resolution that mandates the UN to set course for a global tax leadership role. The historic decision is likely to mark the beginning of the end of the OECD’s sixty-year reign as the world’s leading rule maker on global tax, and will now kick off a power struggle between the two institutions with implications for global and local economies, businesses and people everywhere for decades to come.”

The closing remarks and ‘reservations’ to the support made by the still dominant economic forces that are, broadly speaking, the OECD states, show that the ‘change of power’ may be a slow process. The OECD is by no means dead! But, having come this far in the dilligent historic analysis, it only seems logical that the UN-M will take more of a front seat. As a matter of fact, this trend has already begun with more new treaties being concluded on the UN-M basis than on the OECD-M basis and ‘the average tax treaty’ increasingly resembling the UN-M en decreasingly the OECD-M [source].

With that in mind, we compare the current-day OECD-M to its UN-M counterpart to see how the ‘median’ of international tax arrangements may gradually shift from now on.

The Differences between the OECD Model Tax Treaty and the United Nations Model Tax Treaty

Before we get started, you may want to download our side-by-side visual comparison here:

1. Permanent Establishments

A ‘Permanent Establishment’ [PE] is unincorporated taxable presence in another state. For instance: a super market chain that may open a retail location across the border, would generally become taxabele for the profits of said retail location in its brick-and-mortar state rather than exclusively in its headquarter state. With the rise of the digital economy, the minimum threshold for such a ‘Permanent Establishment’ has increasingly become subject to debate.

The UN-M contains additional wording on the definition of a PE. A building site or construction or installation project becomes a permanent establishment after 6 months, down from the OECD-M’s 12. In addition, the ‘furnishing of services, including consultancy services’ equally becomes a permanent establishment even if the classic brick and mortar [i.e.: an office] haven’t been established. In the age of digital nomadism, this may impact where companies’ corporate income taxes are due.

Also, the ‘agents’-provision is expanded in the UN-M Treaty; when a person [agent] habitually ‘plays the principal role’ leading to the conclusion of contracts that are then routinely concluded without material modification by ‘HQ’ again even without brick and mortar, save where these contracts only pertain to keeping storage, stock or merchandise.

2. Permanent Establishment: ‘Limited Force of Attraction Rule’

This item is a bit more complex. Transfer Pricing, which is pricing transactions between related parties as if they were independent, is a key factor in determining the tax value of turnovers and costs incurred through related party transactions. For the profit allocation between PEs and HQ’s, the OECD stipulates a ‘separate and independent entity approach’, meaning that the profits of a company’s unincorporated but taxable foreign presence should be calculated as though said presence [let’s say: branch] was a complete and completely separate entity.

Under the OECD-M, this approach is hard-cut, meaning for instance that if a person employed by the permanent establishment would sell goods, this sale would generally be allocated to the PE, whereas if a person working for HQ would make an identical sale in the Permanent Establishment jurisdiction, it would not. Transfer Pricing rules would subsequently dictate whether the PE would -if it were independent at least- have to reimburse or remunerate HQ for specific marketing of management costs, or rather whether HQ would pay sales provisions to the PE and absors the sale otherwise, etc.

Under the UN-M, however, such an HQ-sale is added to the Permanent Establishment’s sales, in a rule known as ‘Limited Force of Attraction’. Basically, if a separate group entity would perform business activities in the PE-jurisdiction identical to those of the PE, said other group entity’s activities are ‘added’ to the PE’s. This means that the ‘seperate and independent entity approach’ is, well, less separate and independent under the UN-M.

As per the UN-M Commentary: “The Committee of Experts decided at its 2009 annual session not to adopt the OECD approach to Article 7 arising from the OECD’s 2008 report Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments 28 (the 2008 Permanent Establishments Report). The 2008 Permanent Establishments Report envisions taking into account dealings between different parts of an enterprise such as a permanent establishment and its head office to a greater extent than is recognized by the United Nations Model Convention.”

And: “Under the OECD Model Convention, only profits attributable to the permanent establishment may be taxed in the source country. The United Nations Model Convention amplifies this attribution principle by a limited force of attraction rule, which permits the enterprise, once it carries out business through a permanent establishment in the source country, to be taxed on some business profits in that country arising from transactions by the enterprise in the source country, but not through the permanent establishment. Where, owing to the force of attraction principle, the profits of an enterprise other than those attributable directly to the permanent establishment may be taxed in the State where the permanent establishment is situated, such profits should be determined in the same way as if they were attributable directly to the permanent establishment.“

3. Permanent Estalblishment: No Deduction of Internal Royalties or Similar Fees

This is another major difference: the OECD’s approach calls for the calculation of internal royalty adjustments if these would logically be calculated between separate entities [for instance: where a PE can sell commodities at a premium on the local market due to goodwill derived from marketing efforts performed by HQ].

Under the UN-M, however, the PE-clause states a that no such ‘internal royalties’ or similar fees incurred or charged for, for instance, management services or the use of patents, etc, shall be taken into account – with a caveat for general administrative expenses.

The UN-M has chosen to move this limitation to the text of the Model Treaty and away from more opaque underlying Transfer Pricing rules, so as to ensure that treaty parties -especially where these are a developed and a developing economy state- are fully informed on this topic. The reason seemingly being that such royalty charges are seen to pose a risk for Base Erosion in the source states. Rather, a development or acquisition cost on-charge should be applied as a ‘compensatory charge’, rather than an internal charge with a mark-up for profit.

As per the UN-M Commentary:

“In the case of intangible rights, the rules concerning the relations between enterprises of the same group (e.g. payment of royalties or cost sharing arrangements) cannot be applied in respect of the relations between parts of the same enterprise. Indeed, it may be extremely difficult to allocate “ownership” of the intangible right solely to one part of the enterprise and to argue that this part of the enterprise should receive royalties from the other parts as if it were an independent enterprise. Since there is only one legal entity it is not possible to allocate legal ownership to any particular part of the enterprise and in practical terms it will often be difficult to allocate the costs of creation exclusively to one part of the enterprise. It may therefore be preferable for the costs of creation of intangible rights to be regarded as attributable to all parts of the enterprise which will make use of them and as incurred on behalf of the various parts of the enterprise to which they are relevant accordingly. In such circumstances it would be appropriate to allocate between the various parts of the enterprise the actual costs of the creation or acquisition of such intangible rights as well as the costs subsequently incurred with respect to these intangible rights, without any mark-up for profit or royalty. In so doing, tax authorities must be aware of the fact that the possible adverse consequences deriving from any research and development activity (e.g. the responsibility related to the products and damages to the environment) shall also be allocated to the various parts of the enterprise, therefore giving rise, where appropriate, to a compensatory charge.“

4. But: Acceptance of the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Related Entities

The definitions of ‘Related Entities’ are identical between the OECD-M and the UN-M. Having learned that PE-HQ profit allocation rules differ, however, the question arises whether the same goes for [briefly put] HQ-Subsidiary [incorporated taxable presence] profit allocation.

The UN-M Commentary clarifies that the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines are accepted, in part because their drafting committee was broader than just OECD member states, but possibly also because these Guidelines have become so influential that creating a new or parallel rule set could well be beyond the point and may create openings for asymmetry and double taxation or double non-taxation with that. As per the UN-M Commentary:

“The OECD Commentary continues by stating that [the OECD’s] Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations “represen[t] internationally agreed principles and provid[e]s guidelines for the application of the arm’s length principle of which th[e]is Article is the authoritative statement.” The [UN’s] Committee considers that those guidelines contain valuable guidance relevant for the application of the arm’s length principle under under Article 9 of bilateral tax conventions following the two Models. The Committee also considers it to be highly important for avoiding international double taxation of corporate profits that a common understanding prevails on how the arm’s length principle should be applied, and that the two Model Conventions provide a common framework for preventing and resolving transfer pricing disputes where they would occur. With that aim in mind the Committee has developed the United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries which pays special attention to the experience of developing countries, reflects the realities for such countries, at their relevant stages of capacity development, and seeks consistency with the guidance provided by the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.”

5. Dividends, Interests and Royalties: Center of Gravity Shifts towards Source

The dividend, interest and royalty articles discuss to which extent the source state and the recipient state of such a ‘passive payment’ may tax the item. For the largest part, the provisions are worded identically between the OECD-M and the UN-M, with the small but important detail that dividends may be taxed in the recipient state but not *only* in the recipient state. This leaves a more obvious opening for source states to impose withholding taxes, which is emphasized in the Commentary to the UN-M [we cite the dividend artice commentary]:

“This paragraph, which reproduces Article 10, paragraph 1, of the OECD Model Convention, provides that dividends may be taxed in the State of the beneficiary’s residence. It does not, however, provide that dividends may be taxed exclusively in that State and therefore leaves open the possibility of taxation by the State of which the company paying the dividends is a resident, that is, the State in which the dividends originate (source country). When the United Nations Model Convention was first considered, many members of the former Group of Experts from developing countries felt that as a matter of principle dividends should be taxed only by the source country. According to them, if both the country of residence and the source country were given the right to tax, the country of residence should grant a full tax credit regardless of the amount of foreign tax to be absorbed and, in appropriate cases, a tax-sparing credit. One of those members emphasized that there was no necessity for a developing country to waive or reduce its withholding tax on dividends, especially if it offered tax incentives and other concessions. However, the former Group of Experts reached a consensus that dividends may be taxed by the State of the beneficiary’s residence. Current practice in developing/developed country treaties generally reflects this consensus. Double taxation is eliminated or reduced through a combination of exemption or tax credit in the residence country and reduced withholding rates in the source country.“

Combining this with the Mexico Draft history of the UN-M, it seems that a shift towards more source state taxation may ensue. However, many source states may single-sidedly choose to reduce their source taxes [domestic law] in order to entice the proven effect of attracting more foreign investment. The domestic facility can oscilate more, however, and can more closely reflect the ad-hoc needs of the source state.

6. Fees for Technical Services

The UN-M contains a provision which the OECD-M does not, and it pertains to payments made for technical services. Some [mainly developing] states impose withholding taxes on ‘service fees’, sometimes stated to be ‘import levies on services’ and this provision would create both an opening and a framework for their levying at source.

Fee for technical services are defined as ‘any payment in consideration for any service of a

managerial, technical or consultancy nature’, save certain caveats for the educational space.

This separate UN-M provision is meant to offset the eroding effect that the deductibility of foreign service charges has on domestic tax bases while it may help create a more level playing field with domestic service providers, and is addressed as follows in the commentary:

Article 12A was added to the United Nations Model Convention in 2017 to allow a Contracting State to tax fees for certain technical services paid to a resident of the other Contracting State on a gross basis at a rate to be negotiated by the Contracting States. Under this Article, a Contracting State is entitled to tax fees for technical services if the fees are paid by a resident of that State or by a non-resident with a permanent establishment or fixed base in that State and the fees are borne by the permanent establishment or fixed base; it is not necessary for the technical services to be provided in that State. Fees for technical services are defined to mean payments for services of a managerial, technical or consultancy nature.

This may create a network of tax obligations for cross border services as it creates a framework for source countries to tax foreign service providers on the fees invoiced to resident clients, with the resident state allowing the withholding tax to be deducted from the local tax charge . As per the commentary:

Until the addition of Article 12A, income from services derived by an enterprise of a Contracting State was taxable exclusively by the State in which the enterprise was resident unless the enterprise carried on business through a permanent establishment in the other State (the source State) or provided professional or independent personal services through a fixed base in the source State. With the rapid changes in modern economies, particularly with respect to cross-border services, it is now possible for an enterprise resident in one State to be substantially involved in another State’s economy without a permanent establishment or fixed base in that State and without any substantial physical presence in that State. In particular, with the advancements in means of communication and information technology, an enterprise of one Contracting State can provide substantial services to customers in the other Contracting State and therefore maintain a significant economic presence in that State without having any fixed place of business in that State and without being present in that State for any substantial period.

And as for the meaning of said technical services: “Given the ordinary meanings of the terms “managerial,” “technical” and “consultancy,” the fundamental concept underlying the definition of fees for technical services is that the services must involve the application by the service provider of specialized knowledge, skill or expertise on behalf of a client or the transfer of knowledge, skill or expertise to the client, other than a transfer of information covered by the definition of “royalties”

7. Directors’ Fees and Remunerations of Top Level Managerial Officials

The basis rule for the taxation of income from work, is that the resident state may tax the income unless the work is performed in one single other state for 183 days or more in a 12-month stretch. An exemption is made for payments made to company ‘Directors’ in said capacity; those are taxable in the state of which the company itself is a resident.

It is often speculated that this clause aims to avoid high-level and publicly visible CEOs from being taxable in other states than the state of which ‘their’ company forms a vital part of the infrastructure. Under the UN-M, this ‘circle of subjects’ is expanded also to the company’s top level, the definition of which remains somewhat opaque. As per the UN-M Commentary: The term “top-level managerial position” refers to a limited group of positions that involve primary responsibility for the general direction of the affairs of the company, apart from the activities of the directors. The term covers a person acting as both a director and a top-level manager.

8. Echange of Information and Administrative Capacity as a Non-Factor

Apart from rules on taxing rights, BTTs also contain certain ‘rules of engagement’ and a framework for the exchange of information between states’ tax authorities on each others’ residents in order to assist in the calculation and collection of taxes.

The wording is explicitly meant to cover information even including that of persons or entities not qualifying as ‘residents’ or ‘persons covered’ and may cover information that the collecting state itself does not need for its taxes, but excludes information that would be illegal to obtain under domestic law or that would entail trade, business or personal secrets.

Given the DNA of the UN-M, additional wording is added to the commentary making clear the following: “It is often presumed, when a convention is entered into between a developed country and a developing country, that the developed country will have a greater administrative capacity than the developing country. Such a difference in administrative capacity does not provide a basis under paragraph 3 (b) for either Contracting State to avoid an obligation to supply information under paragraph 1. That is, paragraph 3 does not require that each of the Contracting States receive reciprocal benefits under Article 26. In freely adopting a convention, the Contracting States presumably have concluded that the convention, viewed as a whole, provides each of them with reciprocal benefits. There is no necessary presumption that each of the articles, or each paragraph of each article, provides a reciprocal benefit. On the contrary, it is commonplace for a Contracting State to give up some benefit in one article in order to obtain a benefit in another article.“

9. Entitlement to Benefits

Finally, the UN-M contains a much more expansive Entitlement to Benefits clause, which specifies which persons and entities do and do not have access to the treaty and its benefits. This clause is meant to reflect the intention of eliminating double taxation without creating openings for non-taxation or reduced taxation through tax evasion or avoidance inlcuding treaty shopping arrangements.

In the OECD-M, states can elect for a 2 paragraph simplified clause, or a 7 paragraph detailed clause. The difference being mainly that the simplified version puts the weight of an analysis on whether the benefit-invoker is a ‘qualifying person’, and the detailed clause analysing whether or not the benefit-invoker is not specifically caveated due to possessing certain characteristics of an evader.

Under the UN-M, only the detailed version has been templated. This logically shows a larger priority with avoiding and combating tax avoidance in favor of flexible treaty access.

Put briefly, ‘qualified persons’ [access granted] are state bodies, NGOs, qualifying pension funds and listed entities and their qualifying subsidiaries. For other entities, such as privately owned non-listed entities, additional criteria should be met. Such as: conducting an active business [<50% of income consisting of dividends, interests or royalties], being a headquarter company or being a >50% shareholder in the source company for over 12 months. These tests are topped of with a General Anti Abuse Rule.

Synopsis: The Tree Remains the Same but we Shift Branches and Orchardists.

So: there we have it. Tax Treaties serve to advance business, and increasingly to avoid tax avoidance. The OECD has laid out the important ground work in creating a common language and template, but the rise of developing countries’ economies and the increase in their tax awareness has lead to a resolution that from now on, the tax debate should be held on a larger scale and within the United Nations’ Assemblies.

Starting from a historic perspective, this may lead to the UN’s Model Treaty gradually gaining dominance, which is in effect what’s been happening for some time. And, in my opinion, that is only just as the OECD’s reach has far outspanned its representation. Either way, this shift isn’t much of a landslide, as the two models have a common history and big overlap, with the institutions even directly referencing each others’ work. But in this early shift of powers, I am excited to see what time will bring and have highlighted some differences that may help predict just that. From a tax perspective at least. But that’s where we set out from anyway.