In this post, we walk through the basics and some intricacies of an Employee Stock Ownership Plan [ESOP]. We say ‘an’ ESOP because every plan will be unique; no two companies are the same and neither are any two talent pools, and as a properly working ESOP should interlink Company metrics and goals with Staff preferences and culture, such plans are most always taylor-made and highly specific.

As a result many such plans are also quite sensitive, and therefore often highly confidential. That can make it hard to find an example somewhere, allowing you to visualize how such a plan really looks and works, and what you can expect. So in order to break the ice on the intricacies of an Employee Stock Ownership Plan or ‘ESOP’, we drafted a plain and boilerplate template, free for you to see and download and do with as you please.

Inevitable ‘legal guys’-disclaimer, though: (i) we’ve made the template in a joint effort with ChatGPT, (ii) we are not corporate lawyers but tax lawyers and (iii) Dutch ones, and (iv) we have drafted this for clarifying and explanatory purposes only. So: if you actually plan on implementing an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, please, please get it taylor made as well. You can only ‘give away’ the equity once and you cannot just reverse it once its done. So – do it properly. That being said: let’s get into it!

First of all: What is an Employee Stock Ownership Plan and where does it fit into the realm of Incentive Plans?

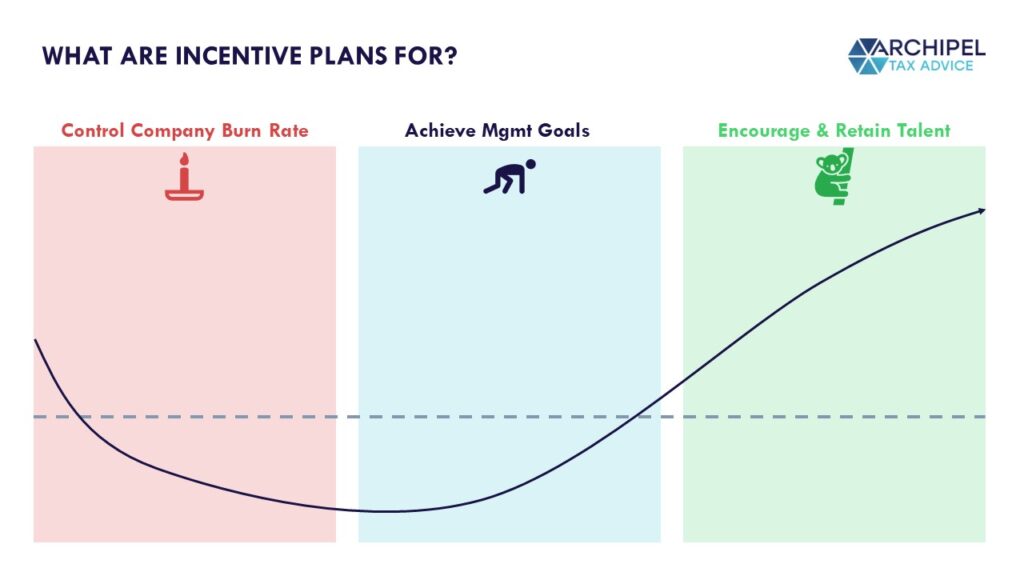

An Employee Stock Ownership Plan, or ‘ESOP’ in this context, is a brand of Incentive Plans. And Incentive Plans, in this context, are financially-driven plans that aim to attract, encourage and reward, and retain talent using equity and/or cash-elements as an addition to the fixed wages related to the contract. Visualized:

In short: when the company is in a developing and cash-burning phase, an Incentive Plan can help extend runway by reducing costs. Less cryptically: by pledging a stake in future values and/or cashflows, people may become more inclined to accept a job position at sub-market rates given the potential of a big upside later down the road, and this conserves the company’s cash position increasing the development time and, with that, the chances of the Company ‘making it’.

A phase later, it’s going to be hard work and the Incentive Plan can help keep people motivated when it’s crunch time. And one phase later still, the company may have become a market benchmark that no longer needs to relies on adventure, but can rather offer market rates. This is more traditional but sometimes also more conventional, and an enticing Incentive Plan can help set it apart from other ‘grown-up’-businesses making the opening offer more intriguing.

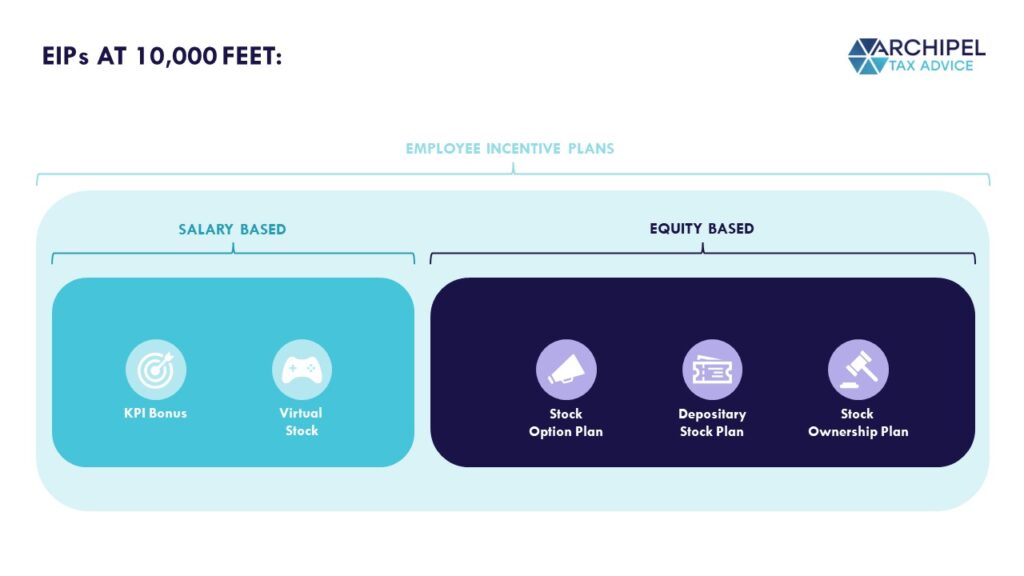

As you may imagine, there are multiple of even endless ways of implementing an Incentive Scheme reflecting these considerations. So to organize our thoughts, we like to broadly discriminate between cash-based plans and equity-based plans, and then between 5 sub-types within these main branches. On that Mindmap [see below], an Employee Stock Ownership Plan is an Equity-based Incentive Plan under which the involved Employee obtains a stake in the company’s shares and, therefore, becomes a co-owner of the company with financial exposure to its financial development and ego-exposure to its clout. Mapped out on our ‘5 Species Tree’:

Buzzword Alert and Untangler

For the remainder of this read, please be aware that the world of Employee Incentive Plans [or EIPs] is full of buzzwords and acronyms, and even acronyms encompassing buzzwords. The ESOP itself is such an interchangeable buzz-acronym as it is commonly used to refer to Employee Stock Option Plans as well as Employee Stock Ownership Plans. The difference is that under the Option-variety of an ESOP, the employee works to vest call-options in company stock, whereas under the Ownership-variety of the ESOP, the employee has stock from the start but may work to vest that. Don’t worry, we will get to that. But just keep in mind that the ESOP we discuss here, is the Employee Stock Ownership Plan.

If you want to learn more about [other] Incentive Plans in general, how they compare, and how to implement a structure that supports company value and goals, please check out these Insights as well:

Back to our ESOP: What is the Basic Idea of an Employee Stock Ownership Plan?

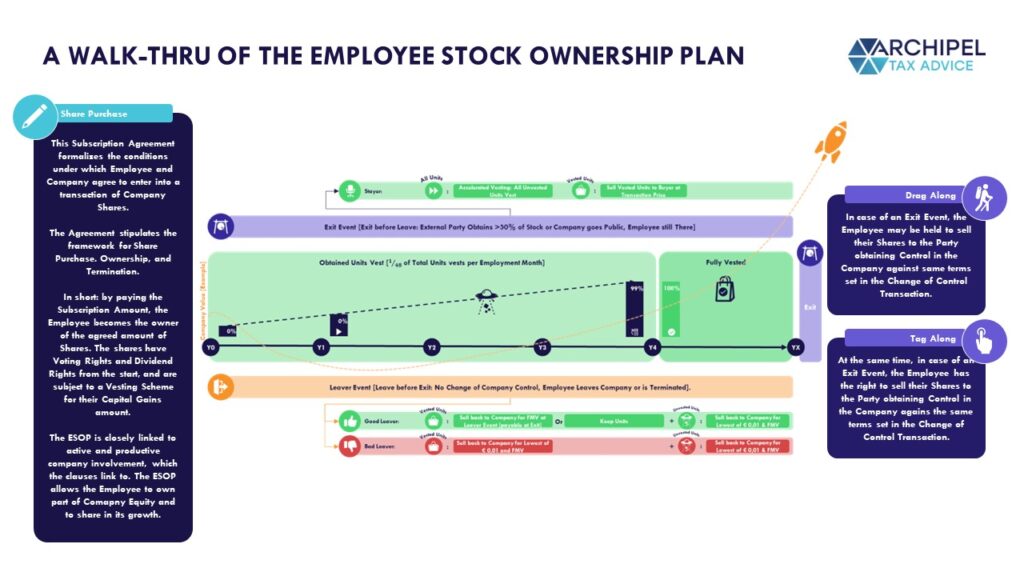

Under an ESOP, the Employee becomes the owner of company stock, subject to specific conditions. In our Template, we highlight the Usual Suspects of clauses and walk through them 1 by 1. But to guide the reading, we summarize our templated idea:

- The Employee purchases Company stock in a pre-public phase, at its Fair Market Value of the moment;

- If [and to the extent that] the Employee does not have sufficient cash to pay said price for the Stock, they can lend the amount from the Company and pay-down the remaining amount in 7 years at 6% interest [Arm’s Length loan];

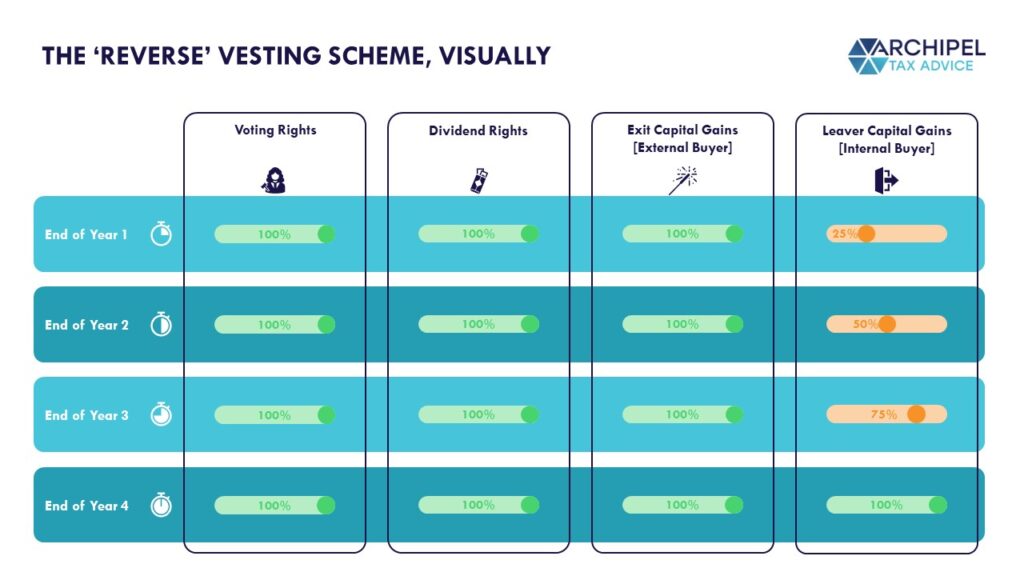

- The Shares so obtainted are fully dividend performing from the start and have voting rights. However, a reverse vesting scheme applies under which the stock is ‘unlocked’ in 4 yearly increments of 25%, which mainly means that if the Employee leaves as a Good Leaver during said period, the Company may repurchase any unvested stock against Nominal Value rather than Fair Market Value;

- In case of an Exit Event, which is a takeover or IPO, all Unvested Shares immediately Vest and Employees still at the Company can participate in the transaction to capitalize on their Gains.

We visualize this scheme as follows:

A Walk-thru Per Clause:

With the template agreement as an exmaple, we want to give a clear view of how such a plan might be implemented. Here’s our voice-over of the different clauses:

Considerations – the Preamble that Sets the Scene

Before the official body text starts, the preamble explains the context of the document. This helps set the scene and context and puts the reader in the right mood, but it can also provide useful background to help understand how a specific clause should interpreted and implemented should its wording prove to be unclear.

For instance: if the Considerations clarify that the ESOP’s goal is to encourage long-term involvement with the company, then a resignation by the Employee should logically be understood to be undesirable even if the Employer would agree to terms underlying the Employee’s inevitable exit from the Company. So for the Good Leaver clause, such a situation would not fall within the scope of an employment ending ‘following mutual agreement’.

1. Parties to the Agreement

In any legal document, it should first be stablished who the signing parties are. This paragraph is pretty clear and standard, and allows the Agreement to be repeat-used but taylored per instance.

2. Subscription Details

This is probably the most interesting paragraph for the involved signatories, as it contains the ‘Bread & Butter’ of the agreement:

- The amount of Shares that the Employee subscribes to [purchases];

- The Price per Share, and with that, of the Batch, that the Employee will be due;

- How said Purchase Price shall be paid, and;

- When all of this is set to take place.

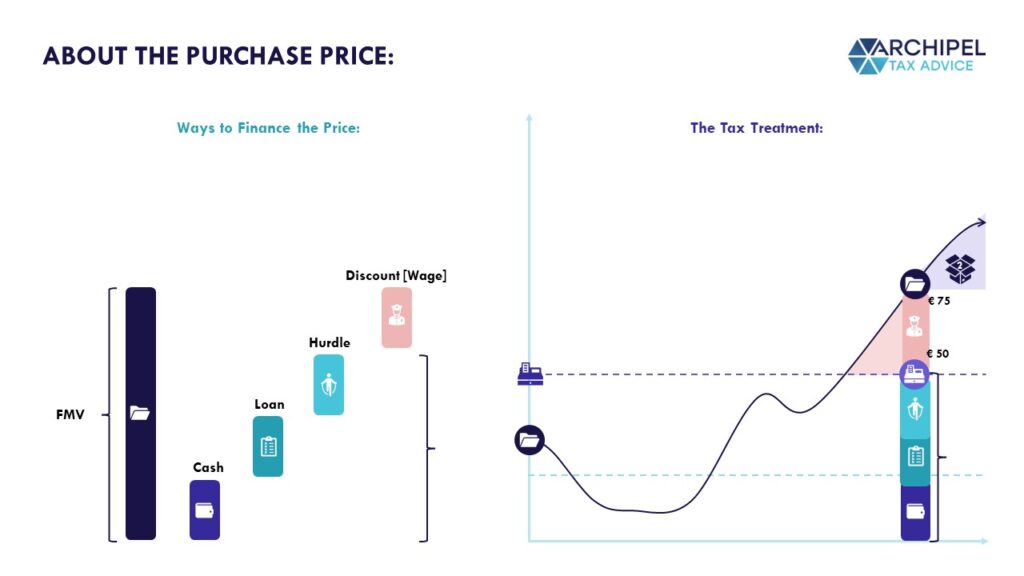

In our Template, we go for a transaction against Fair Market Value, which means that the Employee does not receive a discount on the Shares. Reason for this is that [1] the absence of such an employment-related ‘benefit-in-kind’ that is such a discount allows for a tax-neutral transaction from the Company’s perspective, and [2] an accurate upfront investment asks the Employee for undiscounted ‘Skin in the Game’ and careful consideration on whether to proceed. I.e.: the investment is not gratuitous and there’s gain in outperforming forecasts.

About ‘Skin in the Game’

One of the reasons to ask for an accurate investment in our Template it is used in an ESOP-context, and works with Regular Shares that give voting rights in the Company. By putting their own money into the Company, the Employees are committed to the capital that they now also get to vote and decide on, making for reciprocity. Also: the investment gives the Leaver Clauses [more on that later on] some flesh, as the basics are now laid out for the potential to making a loss in case of early Company departure.

This ‘Downside Risk’ is the arm opposite the ‘Upside Potential’ that creates the Incentive Pincher of this plan, which can support both Investor Attractiveness and Employee Engagement. As per Investopedia:

Skin in the game is a phrase made popular by renowned investor Warren Buffett referring to a situation in which high-ranking insiders use their own money to buy stock in the company they are running. The saying is particularly common in business, finance, and gambling and is also used in politics.

Investopedia, about Skin in the Game

If principals or owners have also invested their own money in the investment vehicle, then prospective and existing investors will translate this move as a vote of confidence. Skin in the game—or insider ownership—also conveys to investors that the company will likely put its best foot forward to generate returns for its investors.

About the Tax Neutrality: Fair Market Value

Any discount on the Purchase Price of an ESOP, be it an implied or explicitly agreed one, is generally taxable as wage, as it forms a ‘benefit in kind’. And although this fact may be an unwelcome one, it is both theoretically logical and inevitable from a tax perspective, as a loophole would arise if Employers could grant non-cash items to their Employees outside of Wage Tax.

Look at this way: with a top marginal Income Tax Rate of 49,5% on employment income in the Netherlands, paying an employee € 5.000 net would cost the Employer roughly (100% / (100% – 49,5%) = 198% of € 5.000, so € 9.900 gross. Of that gross payment, the 49,5% tax part (€ 4.900) goes to the Tax Authorities and the 50,5% net part goes to the Employee. If the Company could grant the Employee € 5.000 worth of shares free of tax, they could effectively pay the Employee an intended € 5.000 net by extending them a shares package worth € 5.000 then purchasing it right back. And the same goes if a discount is not lower than 100%.

So: in order to avoid any tax charges upon the Share Transaction, the Employee should be charged 100% of the Subscribed Share Package.

About Establishing said Fair Market Value

Question then arises, of course, what the Fair Market Value of the Share Package is. For Companies whose stock is in Free Float [Listed Companies], said Fair Market Value is generally a given. But for Privately Owned Companies, establishing the value may be a bit more tricky. Especially where Companies ‘kind of’ intend to ‘give’ shares to their Employees as a catch-up mechanism to back-paid wages of sorts or as a bonus, an evergreen discussion point is whether or not it can be argued that the Company is ‘worthless’ when it is in a pre-profit or otherwise early phase.

When talking about Regular Shares in a viable company, the brief is answer is ‘no’, and the sooner one accepts this fact, the quicker one can work towards an Agreement that works as intended. So how is the Fair Market Value determined? When there is a ‘Reference Transaction’, which generally means a recent-enough third-party transaction such as an Investment Event or a Priced Round, the Valuation used in said Event is generally the preferred and most accurate valuation goven that was actually produced by the Fair Market.

If there isn’t such a Reference Transaction, a calculation based on the Discounted Cashflow Valuation method is the peferred [and often only agreeable] route for the Dutch Tax Authorities because it is theorically most applicable due to being a prospective method, and because it is a ‘dominant method’ in actual Third-Party negotiation processes. We discuss this un further detail in these Long Reads and consider the Valuation Message that a viable Company is worth more than € 0 a given for now 🙂

About Paying the Subscription Price

Once the Fair Market Value is established, the Employee needs a payment method to fulfill their end of the Agreement. Not every Employee may have the cash at hand that corresponds with the Fair Market Value of the envisage Share Package. The most common way to fulfill the Transaction Value, in that case, is through a Shareholder Loan for the remainder.

This means that the Employee can pay the Price to the Company incrementally. And as the conditions of the Loan should reflect an Arm’s Length setting as well [i.e.: any ‘benefits’ would be taxable, including, for instance, an absence of interest where a third party would have negotiated one], the Loan will be agreed on per separate agreement which contains some Market Practice wording on payment schedules, securities and interest percentages.

The benefit for the Employee here, is that the Capital Amount of the Loan remains static in time, while the Company Value increases if all goes to plan. Comparable with, for instance, a mortgage on a home when Real Estate markets perform bullishly:

If the Value of the Company, however, is such that you would arrive on an undesirable or unrealistic Loan Amount for the envisaged share package size, implementing a Hurdle can be an alternative. The Hurdle puts a dispreference on the Shares, meaning the Employee would forfeit certain dividends and/or capital gains, making the profit expectation and therefore value of their package lower. Do note that such a clause can ultimately, and often unintentionally, create a share package with significant ‘internal leverage’ [i.e.: a high pay-out per invested Euro].

From certain tipping points on, such leveraged shares can become above-investment-grade and subject to anti-abuse legislation that aims to avoid bonus income from being ‘dipped’ into equity income, reclassifying it as Wage and taxing it accordingly without allowing for a deduction at a company level. So: tread mindfully when entering these waters.

For more background on Hurdle Shares, the ‘Lucrative Interest’ provision and their interaction, ehck out these Longreads:

3. Conditions Precedent

This paragraph covers certain conditions that must be met before the Agreement can take effect. For instance: the signatory representing the Company declares that the Company is legally able and procedurally authorized to go ahead an actually issue the Shares, and the Employee declares that they are indeed committed to the Company and intent on remaining so. By asking the Signatories to make these declarations, they accept the onus of fixing any shortcomings or consequences thereof.

4. Representations and Warranties

In this paragraph, the Signatories [Company and Employee] declare that they also meet the legal requirements associated with the Stock Ownership that would take place after the Transaction. For instance: the Employee declares that they are mentally and financially sound and, therefore, not subject to legal or financial custody which would effectively place an economic interest in the Company in unintended hands. Also, the Employee ensures that they make the proper disclosures, for instance those arising from Securities Law in their jurisdiction, which may require them to disclose any or certain Equity Stakes in a business.

Simultaneously, the Company declares that they will ensure that the Employee can understand what they’re buying, as the data that it present them with is accurate and up to date and as -for instance- no material but undisclosed law suits are currently unfolding that may impact the Company’s financial expectations.

The reason to ask each other for these declarations despite their gists being so logical, is that it opens an avenue for either party to claim having been ‘misled’, should any such declaration turn out to be untrue after the Transaction. This gives the Parties the possibility to seek a legal dissolution and/or reversal of the Transaction and recourse on each other should play turn out to have been foul.

5. Stock Issuance and Transaction

This paragraph discusses how the Transaction will be priced, settled and executed. In short, in our Template the Employee pays the Transaction Value which consists of the Price-per-Share [Fair Market Value] multiplied with the amount of Shares to be issued.

The Payment takes place for X% in Cash Upfront [wire transfer from the Employee to the Company] and for [100% – X%] through the implementation of a Shareholder Loan, both of which should be ‘with’ the Company at least two weeks prior to the Shares being issued, generally meaning the date upon which Parties are set to mee at the Notary’s office to make it all official.

The Tax Adjustment Clause

This clause, fittingly known as a ‘sliding clause’ in Dutch, implements that the Transaction Value is adjusted if ever a Tax Assessment leads to the conclusion that the Shares were valued under their Fair Market Value when the transaction took place. In order to prevent a situation in which the Company has to take an unexpected hit to its working capital by retoractively ‘bonussing out’ the unintended discount, the adjustment ‘slides down’ to the Subscription Agreement and its conditions are adjusted to represent said Fair Market Value after all. To the Employee’s benefit, however, the same applies if a Tax Assessment leads to the conclusion that the shares were overvalued.

6. Rights and Obligations of the Employee

This paragraph sets out the Rules of Engagement for the Employee. For instance: it clarifies that the Shares that they obtain have Voting Rights and give them full entitlement to Company Dividends, pro rata to their stake in its equity, adjusted for any preferences or waterfalls of course. Also: it reiterartes that the Shares are extended in the context of an ESOP and that they cannot be freely transfered [as the Company wants to avoid ‘Dead Equity’ from arising] and that they are tied to the Employee making an ‘active contribution’ to the Company.

To an extent, putting all of this this in separate writing is also somewhat redundant, as the specific terms and conditions of the involved Shares and share class would already be laid-out in the Statutes [Bylaws] of the Company. However, adding the wording to the Subscription Agreement provides the Employee and the Company with an additional and one-on-one opportunity to reconfirm these obligations, and can help settle any doubt should the other legal documentation give rise to undertainty.

Dead Equity. I’ve seen 100s of different cap tables, and the first red flag I always look out for is dead equity. Dead equity means equity owned by people no longer involved in building the business. Equity is an extremely powerful incentive, and if early on in the process, a significant amount of it is dead, that means that a much smaller number of shares are in the hands of people actually working on the startup.

Techstars’ Brett Brohl in this Blog Post.

7. Rights and Obligations of the Company

This parapgrah eplains the Rules of Engagement for the Company. It is required to provide financial transparency to the Employee, to have recognition for its contributions and support the Employee in its ongoing involvement.

This, too, is a redundant clause of sorts as the Employee, as an investor in the Company, will already have a right to Transparency, and as Labor Law will require the Company to have recognition and development opportunities for its employees. However, re-stating these commitments creates an additional personal an legal layer to work with, and mitigates, for instance, puts an extra back-stop on any options the Company may have to ‘push out’ the Employee to capitalize on a Bad Leaver Event in bad faith. Just an exmaple of course, but still – some additional recourse can always add to trust, even when it’s already high.

8. Vesting Schedule

The Vesting Schemes are widespread in ESOPs. In brief, a Vesting Scheme states how certain rights amass with time, creating an incentive for the Employee to stick around even when the Share Transaction has already been completed. This may be somewhat abstract [or maybe not!] but such a clause can create a situation where the Employee is already the owner of the Shares, whilst certain rights linked to the shares have a statute before they get ‘toggled’ on, perhaps incrementally so.

Watch the Tax Technicality here!

In our Template, we’ve adopted a ‘Reverse Vesting’ schedule, under which a certain limitation on the Stock lapses with time. We often see ‘Vesting Schemes’ where the full financial entitlements grow in time. So: dividend rights, capital gains rights, etc. For tax purposes, however, the ‘Economic Ownership’ of the shares is relevant, as it dictates [1] who is taxed for the proceeds and therefore, what the tax consequences are, but also [2] when the ‘Ownership Transfer’ takes place, and therefore, when the taxable event occurs.

The principle of Economic Ownership follows from a long string of Case Law, and we quote Mr. A.E. De Leeuw’s legal work on it as follows:

Economic ownership, in the context of Personal Income Tax, Corporate Income Tax as well as Gift and Inheritance Taxes, can therefore be defined as follows: an obligatory legal relationship based on which an asset’s total economic interest, consisting of the full exposure to its value fluctuations, risk to its losses, as well as the entitlement to its proceeds, both negative and positive, lies with another party than with its legal owner.

A.E. de Leeuw, Economische eigendom (FED Fiscale Brochures), Deventer: Wolters Kluwer 2018, chapter 2.5

In this spirit, one can imagine that the Employee is not an ‘economic owner’ of unvested shares if this means the Employee is unentitled to said Shares’ dividends or capital gains. And as a result, the tax ownership of said shares transfers upon their vesting, meaning that the taxable event takes place incrementally as well. And when the company value increases with time, this can lead to unintended discounts if the purchase price remains static.

That’s why we choose to let ‘our’ Vesting Scheme pertain only to Leaver Events, meaning that the Employee is full owner of the Shares and their economic effects, except when they Leave the company. In case of a Good Leaver event, then, a diminishing percentage of the stock will be repurchased by the Company for their Nominal Value rather than their Fair Market Value [we refer to the Leaver Clause]. Put visually:

9. Lock-up Clause

A company’s statutes can place limitations on the transferrability of a Stock. This can supercede Trade Law, and the owner of Shares may therefore be restricted in transferring the Shares as they please. As a matter of fact, the Dutch ‘Besloten vennootschap’ [BV] entity form is designed to serve as a closely held entity, and cannot be listed. The idea is that the Company has a Shareholder Registry, and that all Shares ‘Names Shareholders’. This allows the Company to keep track of its Shareholders and prevent ‘Dead Equity’ [as touched upon above].

Although this clause, too, may therefore seem redundant, it does remind the involved parties and adds a layer of legal certainty. Simultaneously, it also sets out exceptions. For instance: if the Employee leaves the Company, they will generally be forced to sell their stock back to the Company [to avoid Dead Equity and put a stop on the ride]. Or: if an external party, such a strategic buyer puts in a bid on the Company’s equity, the Majority Shareholder can accept the offer and force the other shareholder to join the transaction [‘Drag Along’] and if the Company gets Listed, the Employees may choose to put their Shares up for sale in that offering [‘Tag Along’].

In any such cases, the Non-Tradeability is caveated, ensuring that the involved Parties cannot ‘hide’ behind this anti-Dead-Equity-mechanism in order to circumvent their legal obligations under this plan!

10. Leaver Events

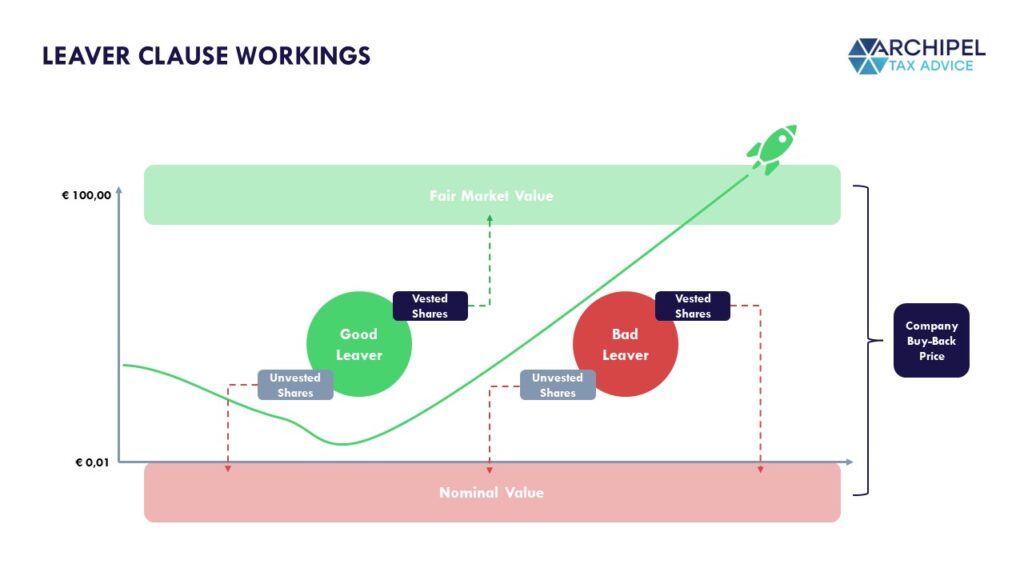

This paragraph highlights what happens if an Employee ‘leaves’ the Company while the Company, otherwise, is just going about its business. As the ESOP is designed to keep valuable staff on board, Leaver Clauses are a necessary add-on to prevent Dead Equity as well as retain wanted staff.

This Leaver Clause discriminates between two types of ‘Leavers’: the Good Leaver and the Bad Leaver. Both are forced to sell back their Shares to the Company upon their Leaving, but the Good Leaver get paid Fair Market Value for their Vested Shares whilst a Bad Leaver gets paid the Nominal Value for their shares [and this is generally € 0,01 per Share, as per the company’s statutes]. What’s the idea?

Good Leaver

This clause lists when people ‘Leave’ under sympathetic conditions, justifying the materialization of their contribution to Company Value development until then, but also an end to Cap Table involvement because, hey, leaving is Leaving.

Examples? Well, in keep with being human, it is good practice to take back the stock but pay-out Fair Market Value if an Employee is forced to stop working due to events out of their hand. Think of something tragic like a critical accident or even death, or something unfortunate like a redundancy following a restructuring or business pivot. From a business perspective [so: apart from the obvious human angles], settling things ‘good’ in such cases not only conserves Company Goodwill, but also makes the conditions of the ESOP more enticing to participate in upfront.

Sometimes, however, a person can Leave for reason within their control and still qualify as a Good Leaver. And it is always a balancing act to get the wording just right for the specific Company. In my opinion, a Good Leaver Clause should always contain wording that allows a realistic way out to an Employee who did excellent work for the Company, but now becomes overcomplete. For example: imagine that a high-paid engineer fulfilled their R&D project and found whatever the Company was pursuing, perhaps much quicker than expected with no exit in sight just yet. Absent a fitting Good Leaver way-out, they may end up in a situation where they remain at the Company with very little to do, but doing just enough not to get terminated because they don’t want to forfeit their shares that are increasingly in the money – and party so due to their doing!

Them staying put, puts a drag on their colleagues and on Company HR costs. No one stands to gain, and in order to mitigate this, an Employee that Leaves following ‘Mutual Agreement’ [in good standing] can be given Good Leaver status, allowing them a Leave at Fair Market Value or even an option to keep their stock in order to participate in an Exit Event. Do make sure, however, to word said ‘Mutual Agreement’ such that id does not cover Settlement Agreement situations that seek to terminate an underperforming or dissonant Employee without Court Involvement.

In our Template, we’ve also put wording in that allows the Company to postpone paying the Leaver Sum until an actual Exit takes place, or until 5 years have passed, whichever comes first. On the one hand, this allows the Company to gather the money as sums can be significant in Accelerated Growth Scenario’s, whilst on the other, it disincentivizes Employees from leaving for opportunistic reasons [for instance: to buy-in to another Company -they’d have to wait a bit].

The Exit Value adjustment bullet, which caps the Leaver Payment to any Exit Valuation per-share, intelocks with this payment-timing idea. this constellation ensures that a Leaver is never paid more than non-Leavers in case of an Exit Event, making sure that Employees do not have an incentive to Leave prematurely when Company Value dips. Because when the going gets tough, the ESOP is also meant to keep the people on the ship!

Bad Leaver

A Bad Leaver is an Employee who gets terminated for, simply put, wrong reasons. For instance, they are Terminated for legal reasons such as Fraud or violating their authorities or important terms of their contracts, or even getting convicted under Criminal Law. In such cases, they are held to sell-back their complete Share Package to the Company at its Nominal Value, which is a statutory Share Capital amount per Share, usually something like € 0,01.

To the extent one would’nt already want to avoid being criminally prosecuted anyway, the significant loss that can incurr adds an incentive to be a Good Boy [he/she/they]!

11. Exit Events

This paragraph highlights what counts as an Exit Event. In our Template, we assume that the Company, if Exited, would either go for an Initial Public Offering [IPO] in which case its stock becomes traded on an official and regulated Stock Echange, or would be acquired by a Strategic Buyer as an acquiring party, meaning there would be a Change of Control. Think of a competitor or a Private Equity investor. Maybe Amazon or Microsoft, maybe Blackrock or Sequoia, who knows!

In case of such an Exit Event, Accelerated Vesting takes place. This means, for the avoidance of doubt, that any Employee who still has ‘Unvested’ Shares, can sell these to the External Investor for their undiscounted Value regardless of Vesting Status. This clarifies that ‘our’ Vesting Scheme pertains only to the Leaver Events.

Also, our Template comtains a Clause that allows the Employee to keep their Shares following agreement with the Company or the new Controlling Party, should they wish to do so. So: even though an Exit Eveny may lead to an ‘Unlocking’ of the Shares, they do no necessarily lead to a materialization of the ride, notwithstanding the drag Along and Tag Along provisions.

12. Drag Along and Tag Along Provisions

It is important to define these Exit Events, because their occurence lifts restrictions on Tradeability: in case of such an Exit Event, the Cap Table Majority may ‘Drag Along’ the other Shareholders [including the Employee at hand] to ensure that no single shareholder may block a complete transaction or negotiate for themselves [making the Company uninvestable], while at the same time, the Employee may ‘Tag Along’ in such a transaction and have the right to sell their Share Package in case of an Exit Event to ensure that their information disadvantage does not lead to them being ‘stuck with stock’.

A drag-along right is a provision or clause in an agreement that enables a majority shareholder to force a minority shareholder to join in the sale of a company. The majority owner doing the dragging must give the minority shareholder the same price, terms, and conditions as any other seller. Tag-along or co-sale rights are essentially the opposite of drag-along rights. Whereas tag-along rights give minority shareholders negotiating rights in the event of a sale, drag-along rights force the minority shareholders to accept whatever deal is negotiated by majority shareholders.

As per trusted Investopedia!

13. Valuation Clause

As the Agreement makes reference to the Shares’ Value and Fair Market Value on numerous occasions, adding a Valuation Clause can prevent uncertainty and disputes by inserting a pre-determined framework on how it is to be established.

In our Template, we clarify that the initial Transaction is intended to take place against Fair Market Value as the buy-in itself is not supposed to be ‘the bonus’. In order to reflect this in the Agreement, we use some wording that we base on Tax Law, stating that our preferred valuation method is to mirror that established in a ‘Reference Transaction’ [a recent-enough third party Equity Event] or a Discounted Cashflow Valuation in absence thereof, to be performed by a Third-Party [with Archipel being the preferred supplier in this case as an Easter Egg].

We use the DCF-Method over commonly seen ‘easier options’ like Multiples Valuations because the DCF allows to adjust for, for instance, times of revenu or growth priorities without skewing outcomes and is also the dominant option as a prospective method in Market negotiations. As per the famous NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran:

In the introduction to discounted cash flow valuation, we observed that the value

of a firm is a function of three variables – it capacity to generate cash flows, its expected

growth in these cash flows and the uncertainty associated with these cash flows. Every

multiple, whether it is of earnings, revenues or book value, is a function of the same three

variables – risk, growth and cash flow generating potential. Intuitively, then, firms with

higher growth rates, less risk and greater cash flow generating potential should trade at

higher multiples than firms with lower growth, higher risk and less cash flow potential.

Aswath Damodaran, The Dark Side of Valuations, NYU Open Source.

For convenience, another link to our Valuations Longreads:

14. Governing Law and Dispute Resolution

Despite best efforts, it is always possible that the involved Signatories may not see eye to eye on a Clause or situation. In that case, an external arbiter needs to break the stalemate. This clause has the Parties commit to a max. one-year out-of-court attempt at reaching Mutual Agreement under the guidance of a mutually appointed Mediator, in this case with Archipel as a preferred supplier as another Easter Egg [we’re funny guys ya know]. If that remains without resolution, the Parties may seek remedy in a legal setting – a.k.a.: escalate the matter to a judge.

15. Confidentiality

This paragraph binds both Parties to confidentiality on the contents of the Agreement and any information, such as financial information or personal details, that they may exchange in its execution or implementation. This means, for instance, that were the Employee gets to access certain financial information about the Company at a Shareholder level, this information is subject to an additional layer of confidentiality. The same goes for certain trade secrets that the Employee, as a Shareholder, may have been able to grasp – which is especially important should the Employee Leave or Exit.

16. Miscellaneous

This paragraph reiterates certain conditions and frameworks that do not justify their own Clause nor fit elsewhere, yet seem important to mention. For instance: how any alterations to the Agreement can be made, how the Agreement can be severed, and that beside this Agreement, there is no shadow document or side letter that governs the framework it puts in place. Consider this the ‘Catch All’ placeholder.

17. Signature

This, of course, makes the Agreement official and puts ints content into working, binding both parties. We recommend turning the signing into a celebration. After all: the ESOP’s preamble already stated that the Agreement is a mutual sign of trust and ambition and a long term thing, so if you’re getting married, might as well have the cake!

Quick Words on the Taxes

We explain the workings from a Dutch Tax Perspective, but many guiding tax principles internationally align so odds are that this quick walk-thru has some bearing everywhere there’s an Income Tax Code.

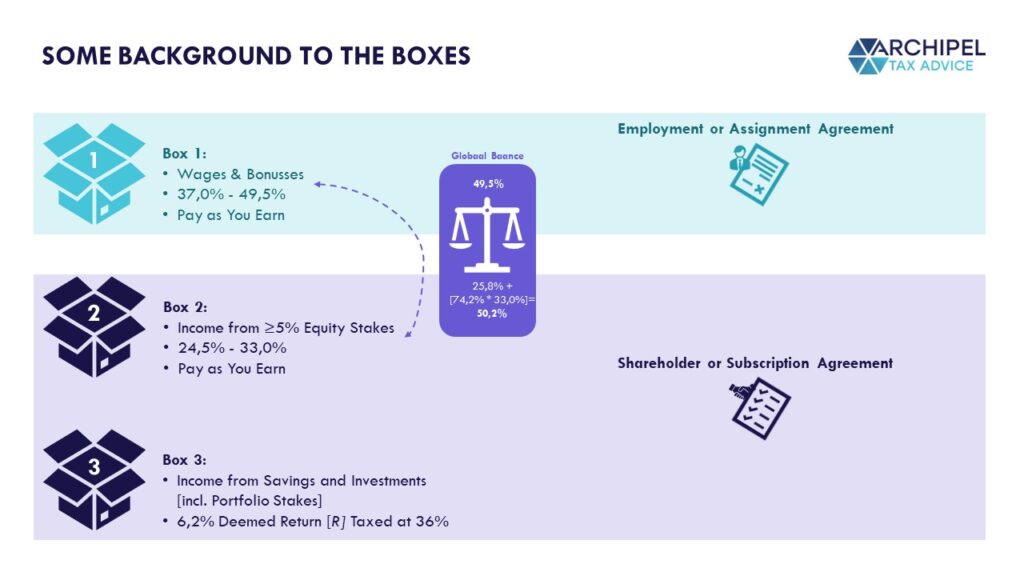

There are two parties to the ESOP: the Company and the Employee. The Company pays Corporate Income Tax, the Employee pays Personal Income Tax, with the Wage Tax that’s been withheld by the employer generally being creditable against the Income Tax calculated.

The Dutch Personal Income Tax Code, so the tax that the Dutch-tax-resident Employee pays, is an ‘Analytical Income Tax Code’, meaning that income derived from different ‘sources’ is taxed differently too. The different ‘Buckets’ that income sources fall into and the regimes that apply to them [i.e.: instructions on how to calculate the income and the applicable rates and timing] are known as ‘the Boxes’. And there’s a logic to the different rates that apply to the different income sources they encompass:

The basic reasoning is that ‘Active Income’ from independent work or employment is taxed at marginal rates up to 49,5%. If a proprietor should choose to incorporate, they would first pay Corporate Income Tax at bracketed rates up to 25,8%, then pay up to 33% Personal Income tax on the dividend received after Corporate Income Tax. Onn a cumulative basis, they would then pay a top rate of 50,2% cumulative tax, meaning there isn’t a clear tax reason to incorporate or not. This is by design and leaves only other considerations.

Box 1 is a relevant regime when we look at obtaining the shares under an ESOP, as any discount falls within that bucket as a ‘benefit in kind’. After the stock has been obtained, however, its proceeds will be taxed as Equity Income [provided no anti-abuse measure ‘dips it back’ to work-income] under the Box 2 or Box 3 regime, depending on the involved stake and structuring. This is a whole stand-alone advisory item by the way [so do ask your advisor about this] but generally speaking: an incentivized Employee under a broadly implemented ESOP-plan would fall into Box 3 as they rarely tip the 5% direct stake threshold.

Nonetheless, we take Box 2 as an example. Even though the cumulative rate for Box 2 income adds up to 50,2% for dividends as tax is due at 2 levels, this does not apply to Capital Gains; if a shareholder [or an Employee-shareholder] sells their stake, this logically only forms income for said Shareholder and not for the underlying company, meaning the tax is reduced to one level – that of the shareholder. This means that Capital Gains can effectively be materialized at discounted rates, and that the greater a percentage of the Equity Value Growth-ride the Employee can capture under the Equity Regime, the greater their benefit is.

This also cotextualizes the Incentive-angle of the ESOP; even though the buy-in is one against Fair Market Value, opening up the ESOP in an early stage allows the Employee access to friendly-taxed Capital Gains and -if all goes well- return rates that are otherwise usually reserved for Venture Capital or Private Equity Funds as such returns are built on pre-IPO access to high-growth businesses. And as access to VCs or PEs, in turn, is generally reserved for the wealthy given the fact that minimum investment amounts can be significant given the compliance costs or legal requirements [such as Qualified Investor status], an ESOP Plan can be a game changer even if it is based on an FMV-buy-in.

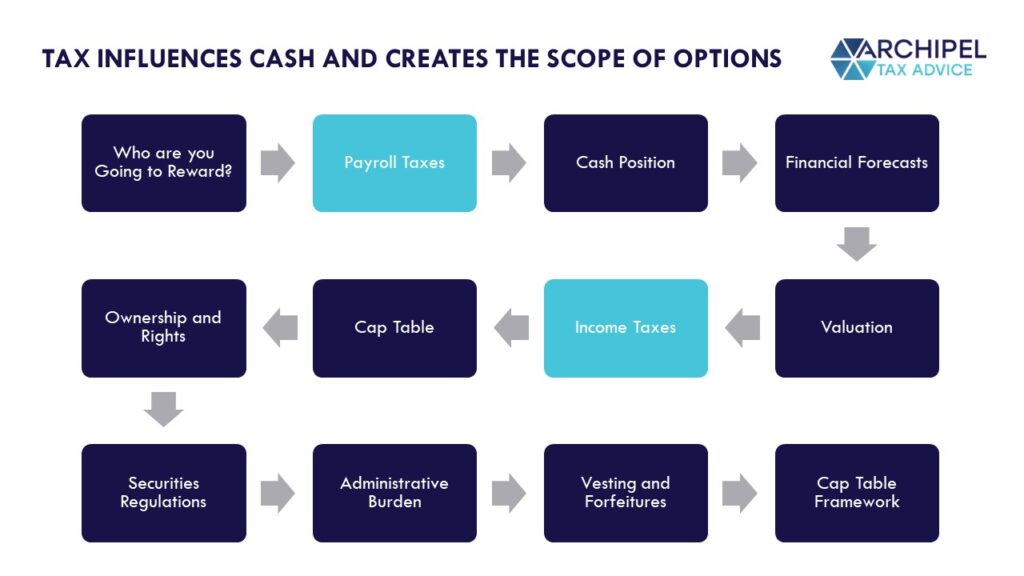

Although Tax is often not a leading factor when creating an ESOP, its parameters can form a good starting point for their design as there are so many interlinking tectonic plates to ‘the numbers’ underlying the plan, that Tax can sometimes be the clearest framework:

How Can we Help Create your ESOP?

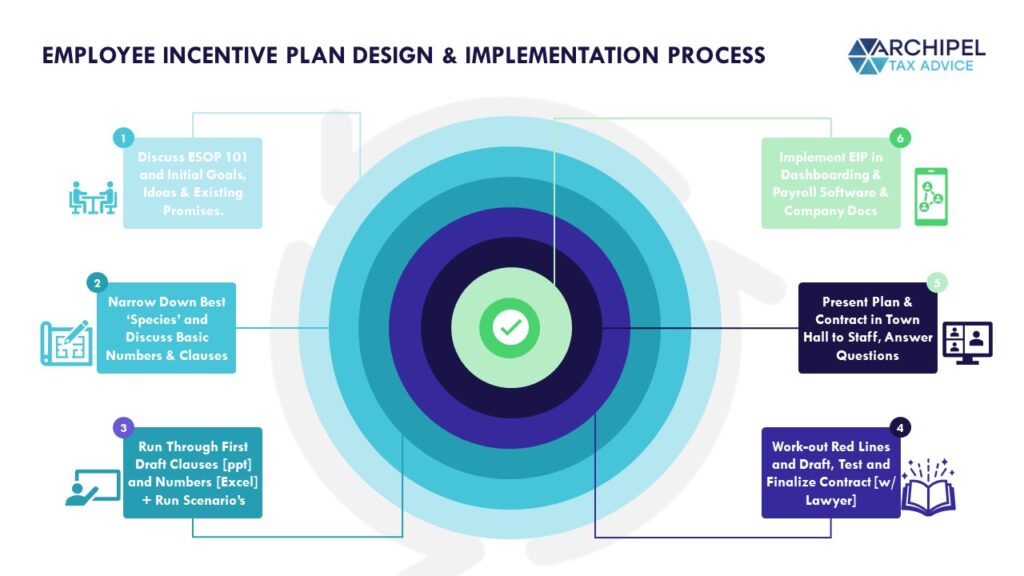

Like we said at the start: no two Companies are the same, and so no two ESOPs should be. But by combining creativite forces, we always arrive at a best option. And after having ‘done this’ quite a lot of times, we conclude that an ESOP design process often takes follows a similar pattern:

Want to Discuss or Ask a Question? Book a Slot, it’s on the House!

Here’s my Calendly – feel free to get in touch, this stuff’s my favorite and the tax is my work. So: happy to connect and explore, and to propose an approach if you seek it!