In this article I describe what so-called hurdle or threshold shares (hereafter: ‘hurdle shares’) are, why you would want to use hurdle shares, what the financial consequences of a hurdle are for the hurdle shareholders and how hurdle shares relate to the so-called lucrative interest rule of article 3.92b Dutch Personal Income Tax Act 2001.

Click here for this article in Dutch!

De Hurdle Share: wat is het en hoe werkt het fiscaal? – Archipel Tax Advice

What are hurdle shares?

Hurdle shares are ordinary shares to which a quantitative, financial dispreference (hurdle) is attached. As a result of that dispreference, the holder of such a subordinated share has to forgo a certain amount of share proceeds (dividends / capital proceeds) for the benefit of the other shareholders. As soon as the hurdle amount has been fully forgone, it lapses and from that moment on, in principle, the holder of that share is entitled to dividends and capital proceeds (just like the other shareholders) with respect to that share.

Below I will further describe the hurdle based on similarities and differences with subordinated ordinary (non-hurdle) shares and debt.

Similarities and differences with subordinated (non-hurdle) ordinary shares

An ordinary share, compared to a preferred share, is quite similar to a hurdle share, because the preference of one share means a subordination (dispreference) of the other share. However, there is at least one other major difference between (i) hurdle shares versus non-hurdle shares and (ii) ordinary shares versus (cumulative) preferred shares. A preferred share usually does not share in the residual profit1, while an ordinary share does.

It is important to realize that the extent of difference or similarity in terms of total proceeds depends on several factors, such as:

- the amount of the cumulative preferred share capital including share premium;

- the dividend preference;

- the amount of the hurdle;

- the ratio of the hurdle shares in relation to the total share capital; and

- the timing and amount of dividends and exit proceeds.

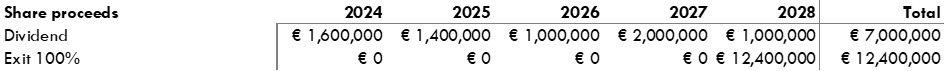

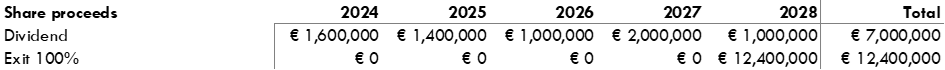

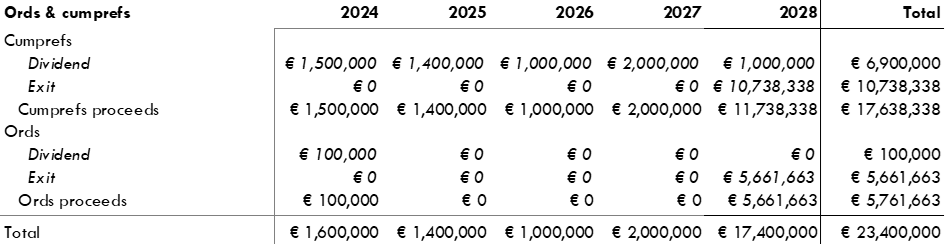

Below I will provide two sample calculations to clarify this. ‘Ords’ stands for ordinary shares and ‘Cumprefs’ stands for cumulative preferred shares. We take the following timeline with corresponding proceeds.

When distributing the proceeds on the cumulative preferred shares and the ordinary shares, a dividend preference of 15% over a contribution of €10,000,000 applies.

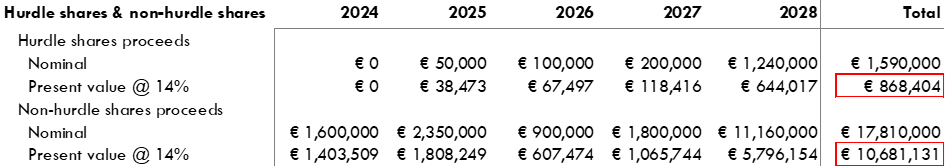

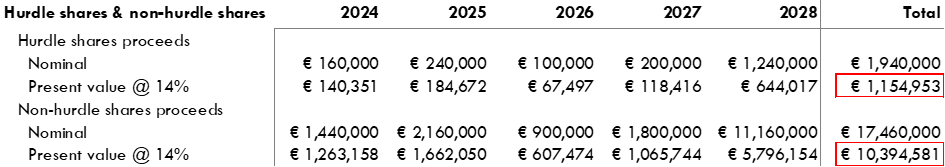

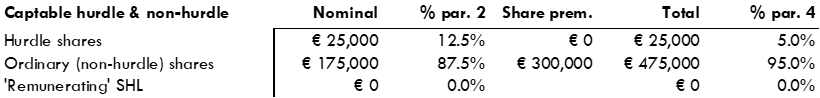

If the ratio of the number of hurdle shares to the total number of shares is 10% and the amount of the hurdle (being the only difference) is €350,000, the distribution is as follows.

The above shows how hurdle shares work and illustrates the difference with subordinated (but non-hurdle) ordinary shares.

Similarities and differences with debt

A hurdle is also often compared to debt. However, a hurdle is simply not the same as debt. If the hurdle shares are sold, whether or not upon exit, and the proceeds do not suffice to fully cover the hurdle, the (then former) holder of the hurdle shares does not have a remainder of debt to the other shareholders. Thus, the hurdle is not an amount that must be repaid to the other shareholders in advance, unlike ‘real’ debt. The difference between these two instruments lies, above all, in the risk and the commitment of the parties involved. In addition, debt usually bears interest while there is no such thing for a hurdle.

Another difference is that debt does not reduce the value of the share, while the (statutory) hurdle does. Note in this context that for the person who acquires shares against fair market value there is no difference between the impact of a hurdle and the impact of debt on that person’s equity.2 If you disregard that risk, debt without interest can be economically equivalent to a hurdle, provided that the hurdle shareholder first uses the dividends and return of capital to repay the debt.

Below I will provide an example of non-interest bearing debt (to the other shareholder), where the indebted shareholder again holds 10% of the total number of shares in the company’s capital. The repayment obligation has been contractually rendered fully dependent on the share proceeds.

In the above example you can see the full similarity with the sample calculation of the hurdle in a scenario where the debt can be repaid with the share proceeds. The difference, however, occurs when the risk inherent to the debt materializes and the share proceeds are insufficient to repay the debt. It should be noted that the extent of that risk (and thus the difference) depends again on the securities/collaterals that debtor and creditor have agreed upon. After all, if no fixed term has been agreed and the interest-free debt can simply continue to exist for as long as the needed share proceeds do not arise, then the risk for the debtor is actually exactly as big as with a hurdle of the same size, namely: nil.

In principle, as long as there is an obligation to repay, the debt will continue to be regarded as debt, even if the repayment obligation is conditional and the payments are dependent on future, uncertain events. According to case law of the Dutch Supreme Court this does not make any difference. If you want to learn more about this, please click here. However, that lack of risk can have tax consequences. The absence of interest can be regarded as a taxable benefit, the debt can be requalified for tax purposes (in the profit and ‘result’ tax sphere) into equity and in an extreme case the debt could potentially be completely disregarded as a result of which the acquisition of the shares would be deemed to have taken place ‘for free’ for tax purposes, with the full value of the shares being the taxable base.

But the hurdle is not debt. If the hurdle is incorporated in the articles of association, there will not even be a short-term debt from the holder of the hurdle shares to the other shareholders. If the hurdle has, however, been incorporated in a participation or shareholders’ agreement, short-term receivables and payables may come into existence, for example if the dividend declaration date and the payment date are different and the hurdle mechanism latches on to the dividend declaration date. But as soon as the non-hurdle shareholders have received their portion from the hurdle shareholders, that creditor-debtor relationship disappears again.

What is the benefit/use of hurdle shares?

A hurdle reduces the expected proceeds on the share. This renders the share less attractive to hold and thus the share gets a lower fair market value. The lower value of one share automatically implies a higher value of the other share. That can be seen in the sample calculations above, which show that the amount of the hurdle benefits the other shareholder. Those shares have increased in value by an equal amount.

There can be several reasons for that devaluation. Suppose an employee, for example in the context of an incentive plan, joins the share capital, but that person cannot or does not want to afford the value of ordinary (non-hurdle) shares and the tax exposure that comes with a large ‘benefit in kind’ is too expensive for that employee or the employer. Feel free to read this article on how the taxation regarding a share award works.

A hurdle can also offer a solution from a tax perspective for a typical fund or target manager who, on the basis of a management agreement, whether or not through a personal holding or management company, performs work for an operating company.

Of course, the low value can also lead to the fact that the participant achieves a relatively large result with a relatively small investment, the so-called ‘lever effect’, or simply: leverage. After all, after covering the hurdle, the hurdle shares fully share in the residual profit.

Obviously there is also the situation in which the institutional investor requires to secure its investment, including its returns, first before the management sees any, just like with preferred shares.

The reasons mentioned above for incorporating a hurdle can, in principle, also be solved by debt. As I explained earlier, the big difference between a hurdle and debt is the risk borne by the debtor.

A combination of debt and a hurdle is also possible, which would entail a loan being taken out for (a part of) the share value as reduced by means of a hurdle.

What is the value effect of a hurdle?

So we know that the dispreference that the hurdle represents, lowers the share value. We also know that – ceteris paribus – the value of the total share capital does not change by implementing a hurdle for a certain number of shares. After all, the decrease in value of the hurdle shares implies an equal increase in value of the other shares. Quantifying that value difference depends, to some extent, on subjective parameters, such as the expected absolute share proceeds, the timing of those proceeds and the cost of capital rate at which they are discounted.

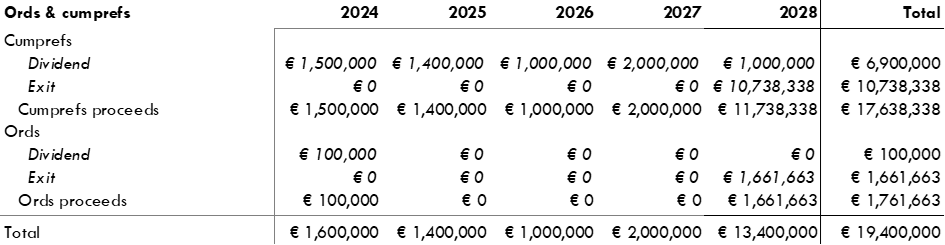

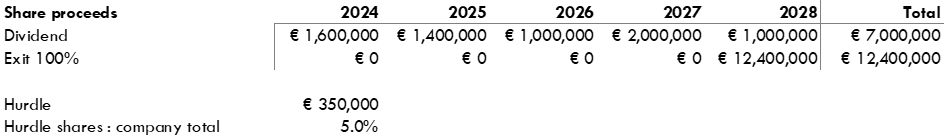

I will provide another example and assume the following. At the time of the share acquisition, there is already a reasonable expectation that after 5 years 100% of the shares (whether or not through a drag-along provision) will be sold for approximately €12,400,000. The dividend proceeds in those years have also been reasonably forecasted. We take the following forecast.

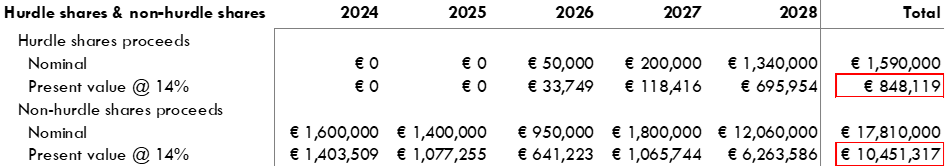

A 10% shareholding has a hurdle of €350,000, exactly as in the sample calculations already included above. We assume the discount rate is 14% (more on that in this article). The value of the different types of shares is then as follows:

The amount outlined in red of €848,119 is then, at the time of the acquisition, the value for tax purposes that is relevant in economic traffic. Without the hurdle, the value would have been as follows:

Without the hurdle the value of the same 10% stake is €281,825 higher than with the €350,000 hurdle. The value-decreasing effect of the hurdle is smaller than the hurdle itself. This has everything to do with the cost of capital that reflects investment risk and monetary depreciation. Whatever cost rate you use, simply subtracting the amount of the hurdle from the value that the shares would have had without a hurdle is therefore not entirely appropriate when quantifying share value with a hurdle.3 This ‘deviation’ becomes smaller as the hurdle is covered more quickly in the forecast.

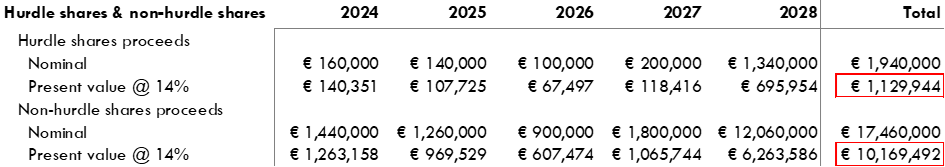

Below I will provide a sample calculation to clarify this. In the forecast year 2025 an additional €1,000,000 dividend is paid out but the exit yields €1,000,000 less.

In absolute terms, each shareholder still receives the same, only the timing differs from the forecast in the previous sample calculation. That has – ceteris paribus – the following effect:

With the changed timing of the share proceeds, the value of the 10% hurdle stake is now €868,404. That is €20,285 more than with the previous forecast (€848,119), because the value of the total share capital is of course higher when the share proceeds lie less far into the future.4 However, the comparison should be made with the new forecast without hurdle. That looks as follows:

The value effect of the €350,000 hurdle with this new proceeds forecast is now greater, namely €286,550, than the €281,825 under the previous proceeds forecast.

To see how hurdle shares fit within the lucrative interest rule, it is worth getting to grips with that rule first (to the extent necessary).

The lucrative interest rule

The lucrative interest rule (also known as: carried interest rule) of article 3.92b Personal Income Tax Act 2001 entered into force in 2009 in order to tax excessive (labor) remuneration components more heavily than before. Previously, a stake not held for business enterprise purposes was almost always covered by Box 2 or Box 3, solely depending on the relative interest that the taxpayer held in the issued capital of a type of share. This was also the case if the share proceeds that the taxpayer could receive therewith entailed a strong incentive for that person to work hard and do a good job.5

The tax treatment of (the proceeds on) such instruments thus implied that the (later deemed excessive) proceeds that taxpayers realized on their shares was, from a tax perspective, seen as remuneration for providing capital and not for providing labor. Shortly after the financial crisis erupted, this view came to be regarded as undesirable.

The entry into force of the lucrative interest rule was an attempt to change that. This rule aims to turn the holding of certain shares into an ‘other activity’, as a result of which the fruits thereof are taxed as ‘income from other activities’ in Box 1. See for more info this article.

First of all, the proceeds that the shareholder expects to derive from his shares must, in view of the circumstances under which the shares were acquired, can reasonably be considered to be intended to constitute remuneration for labor personally performed by that shareholder. This indicates a link of the share proceeds to labor, thereby justifying a labor tax.

If you pay the fair market value for a package of shares, then included within that purchase price are all of the expected proceeds (including possible aggressive scenarios and upward spikes), as a result of which there simply can’t be any labor remuneration, economically speaking. However, the legislator noted that, for purposes of this rule, an intention to provide labor remuneration may nevertheless be considered present. In my view that remark is economically indefensible, but I understand that the legislator wanted to guard against situations where business valuations (which after all depend on many arbitrary factors) are deliberately and unduly calculated very pessimistically. What matters most is that the legislator’s comments are honored in our tax case law as well, which means that a share acquisition that is untaxed under wage tax law (because purchase price = fair market value) does not preclude the later application of the lucrative interest rule.

Certain requirements are also imposed on the shares themselves. The Dutch legislator stated that it concerns shares with a certain leverage (translated to English):

“The proposed first paragraph in conjunction with part a of the second paragraph relates to “leverage situations”, as described below. […] With private equity funds that establish an (intermediate) holding company to act as the acquiring entity, the share of debt capital is higher than usual at that entity, creating a greater leverage effect, or potential (excess) profit, for the providers of equity capital in proportion to the equity capital. An attempt is then made to create a further (extra) leverage effect within equity capital itself, for example by means of several types of shares, purely for a very limited part of that equity capital. The last-mentioned part of equity capital fully shares in the “excess profit” […]. Those who perform work for the benefit of private equity funds share in this lucrative part of the equity capital of the (intermediate) holding company.”

The Dutch legislator has expressed such ‘disproportionate sharing in excess profits’ in the wording of the act by cumulatively requiring the following for the application of the lucrative interest rule:

- It must involve different classes of shares. For the interpretation of the term ‘class’, article 4.7 Personal Income Tax Act 2001 is decisive. Certain shareholder loans can also qualify as a separate class of share for the application of these criteria.

- The lucrative share class is subordinated to one or more other types (or certain shareholder loans); and

- The lucrative share class accounts for less than 10% of the total share capital (including certain shareholder loans of the company.6

This is also referred to as the main rule (for shares) of the lucrative interest scheme. Note, therefore, that to establish the leverage effect of the shareholder’s stake, it’s not the ratio between contribution and subsequent proceeds that’s relevant. The main thing that’s relevant is the ratio between the issued capital of the subordinated share class and the company total including certain shareholder loans. This leverage effect is also called the envy ratio.

The leverage effect

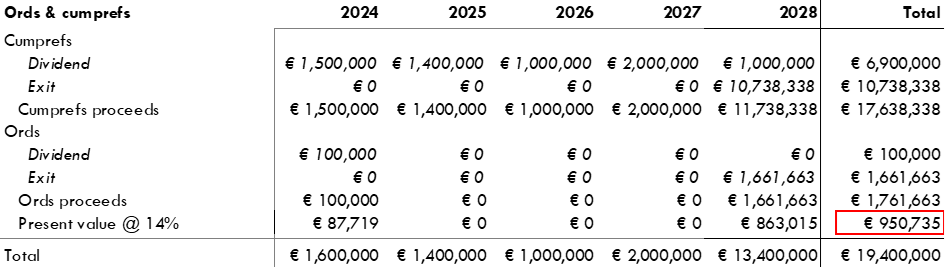

The greater the subordination, the higher the envy ratio. In other words: the greater the risk for the subordinated shares, the greater the potential upside (excess profit) for the relatively small number of subordinated shares in a financially favorable scenario. This leverage effect is illustrated below in a sample calculation. We again take the scenario with the ordinary and cumulative preferred shares, where the capital contribution to the 15% dividend preference cumulative preferred shares is €10,000,000, using the old proceeds forecast. The valuation of all ordinary shares combined can, using a discount rate of 14%, be shown as follows:

The total nominal proceeds for the ordinary shares of €1,761,663 represent, when discounted, €950,735. Now suppose that this is also the purchase price paid by the holder of those ordinary shares. The year-on-year return (the ‘IRR’) of the ordinary shareholder is thus forecast at 14%. However, the exit forecast will turn out to be vastly exceeded. The 100% exit after 5 years appears to be not €12,400,000 but €16,400,000.

That €4,000,000 higher capital gain accrues in full to the ordinary shares, which thus generate €5,761,663 in exit proceeds. Combined with the (admittedly, in hindsight vastly undervalued) purchase price of €950,735, the holders of the ordinary shares now have an IRR of 43.4%. That is the leverage effect, the result of the envy ratio. The downside is that in a worse-than-forecast scenario, the ordinary shares actually miss out, while the cumulative preference shareholders are repaid first.

In the absence of an Advance Tax Ruling (Dutch: vaststellingsovereenkomst, VSO) with a share valuation, a wage tax inspector can still try to ‘repair’ this within the additional assessment period (5 years) by arguing that the share value at the time of acquisition must have been higher already. However, for the fair market value, only the situation as it was known and could reasonably have been known at the time of acquisition is relevant. This means that facts and circumstances that were unknown to the taxpayer and their employer at the time but which plausibly were already at play can also be taken into account when determining the fair market value of those shares. So the hindsight reasoning does work in the tax inspector’s favor and can sometimes lead to corrections. Read more about this in this article (control+F “Chinese vaas”).

The catch-all provision

The legislator realized that leverage effects can, in economic terms, also be created with elements other than the nominal (issued) share capital. The legislator stated the following: “It is also possible that leverage effects comparable to the examples below can be achieved in situations other than those covered by the three criteria above by working with extreme debt-equity ratios. If it turns out that this is being taken advantage of in practice, there will be no hesitation in introducing additional regulations.”

Not only shares, but also debts, receivables and certain rights can fall under the lucrative interest rule. As far as those rights are concerned, they must be “rights as referred to in the fourth paragraph”. Article 3.92b paragraph 4 Personal Income Tax Act 2001 states, in brief: “Rights as referred to in the first paragraph are property rights which, in view of the facts and circumstances, economically correspond or are comparable to shares as referred to in the second paragraph […].” This concerns situations, for example, where a certain class of shares nominally makes up at least 10% of the company total, but if you include all share premium, that share class still makes up less than 10% of the company total.

Until June 26th, 2023, shareholder loans that were not requalified into capital from a tax perspective were, according to the Dutch Supreme Court, not included in the denominator of the fraction resulting from the 10% test. In response to that judgment of the Supreme Court, the State Secretary for Taxation and Tax Authorities, Mr. Van Rij, announced a proposal to amend the lucrative interest rule. As from January 1st, 2024, the lucrative interest rule has been expanded accordingly, as a result of which “loans contributing to the labor remuneration” are included in the issued share capital for purposes of the lucrative interest rule. According to the explanatory memorandum, shareholder loans that have an effect economically comparable to preferred share capital are specifically referred to. Below I will provide a brief sample calculation to clarify this:

By including the ‘remunerating’ shareholder loan in the 10% test, the ordinary shares now make up only 5% of the company total, bringing the ordinary shares mathematically within the lucrative interest rule.

The lucrative interest rule and hurdle share

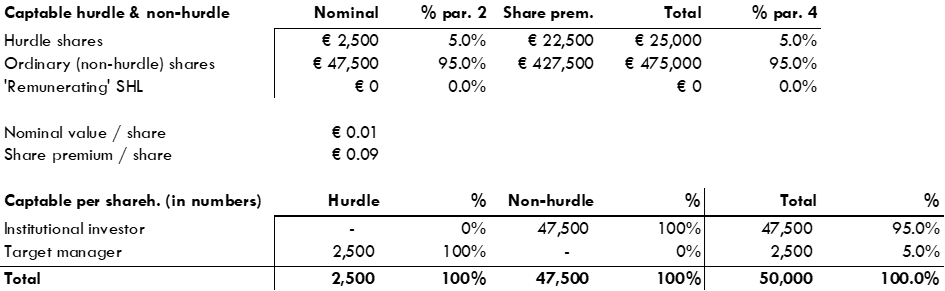

If a hurdle is not included in the articles of association but is stipulated in an agreement, there is, in principle, no separate class of shares for Article 3.92b, paragraph 2, section a Personal Income Tax Act 2001. However, given the economic similarity to the statutory hurdle, hurdle shares can still be considered as ‘rights as referred to in the fourth section.’ In essence, the hurdle shares, in economic terms, are still a distinct, subordinate class of shares that can fall within the lucrative interest rule. Below, I provide a numerical example to clarify the matter.

Through paragraph 4, the non-statutory hurdle shares still fall within the mathematical framework of the lucrative interest provision, as the hurdle shares are economically subordinate and, including share premium, constitute only 5% of the company total.

The view of the Tax Authorities on hurdle shares

In June 2017, the Dutch Tax Authorities published a report titled ‘Private equity and taxation.’ In this report, they address hurdle shares in the context of the lucrative interest rule. They state the following (translated to English):

“If there is no distinct class of shares, the conditions of the second paragraph of Article 3.92b Personal Income Tax Act 2001 are not met. However, it may still be possible to have a lucrative interest under the safety net of the fourth paragraph of Article 3.92b Personal Income Tax Act 2001. Refer to section 9.4.7.1 and beyond for details, including rights that are economically comparable to held shares and so-called ‘threshold’ or ‘hurdle’ shares. […]

9.4.7.1.2 Threshold or Hurdle Shares

In practice, it is increasingly common for there to be a fiscal distinction (assessed under Article 4.7 Personal Income Tax Act 2001) of a single class of shares (as indicated in the company’s articles of association), while economically, there are different types of shares. This distinction arises from the shareholder agreement entered into among the shareholders.

For instance, such a shareholder agreement may specify that the shares held by the manager only participate in profits above a certain amount. For the purposes of substantial interest, there is still a single class of shares, as this agreement is not documented in the company’s articles of association. Legally, these agreements bind only the shareholders but do not pertain to the shares themselves, maintaining a single class of shares as per Article 4.7 Personal Income Tax Act 2001. Economically, however, there are distinct classes of shares since the shares held by the manager participate in profits only above a certain amount, known as the “hurdle” or “threshold.” Economically, the shares held by the manager are also subordinate to the other shares of the private equity fund. In the distribution of the company’s proceeds, these proceeds first go to the shares held by the investors up to a certain limit (the threshold). After that, if there is still surplus income (excess profit), this surplus is proportionally distributed between the shares held by the manager(s) and the shares held by the investors.

Effectively, the shares held by the investors in the fund are preferential up to the threshold amount, and the shares held by the manager are subordinated since they only participate in profits after the threshold amount is exceeded. However, this subordination is not determined by the company’s articles but rather through a contractual agreement. The profit distribution of the excess income typically occurs proportionally, with both investors and the manager receiving a proportional share of the excess profit. What makes this case unique is that the providers of the actually preferential capital also share in the excess profit proportionally.

Shares held by the manager that only participate in profits after reaching the threshold, economically resemble ‘Article 3.92b, paragraph 2, section a shares.’ If the amount contributed by the managers on the shares they hold is less than 10% of the total amount contributed on all shares in the company, such shares held by the managers are considered lucrative rights as defined in Article 3.92b, fourth paragraph, 1st to 4th lines, of the Income Tax Act 2001. The value progression of shares held by the managers then follows the value progression of shares as defined in Article 3.92b, second paragraph, section a, Personal Income Tax Act 2001.”

However, as I described earlier, a hurdle does not necessarily economically function the same way as a dispreference resulting from subordination to preferred shares. Therefore, the value progression does not always have to be the same. Nevertheless, I do agree with them, as mentioned earlier, that it is economically similar enough to such a dispreference to fall within the scope of paragraph 4.

I do acknowledge that, in June 2017, they took a straightforward approach by stating that the 10% test applies to the fourth paragraph, where (before the recent legislative change) only (fiscal) capital is considered. However, I would like to emphasize that, in principle, the contribution of the managers does not matter. The only relevant factor is what, generally speaking, has been contributed to the subordinate class of shares, regardless of who made the contribution, compared to the total capital of the company.

How does this work in practice, and is it possible to structure around it?

The catch-all provision of paragraph 4 is a deliberately vaguely worded anti-abuse measure. However, since the 10% test also applies to paragraph 4, the cap table can still be structured in such a way, including hurdle shares, that the hurdle shares fall outside the lucrative interest scheme. I will illustrate this in a sample calculation below, whereby I mimic a situation that falls within the description by the Dutch Tax Authorities.

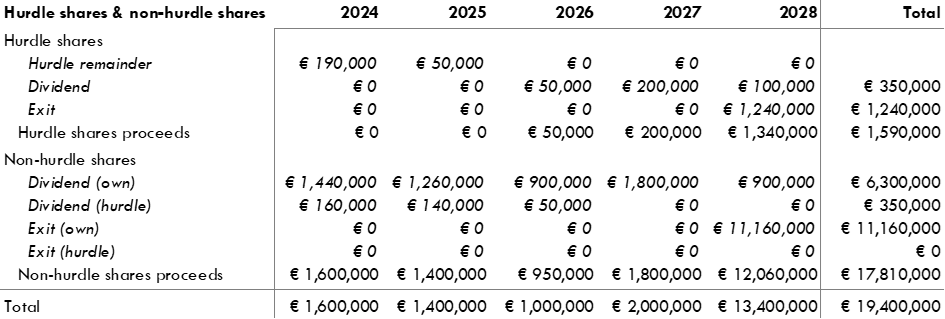

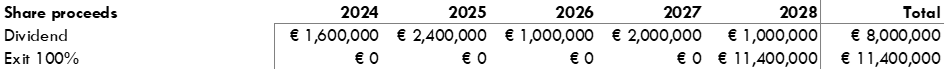

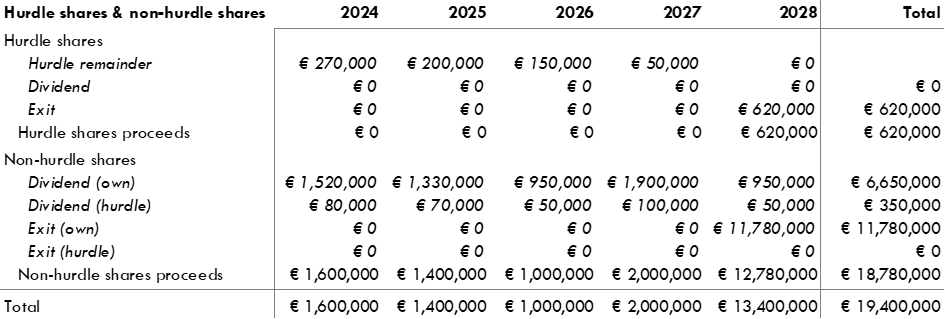

Please note that the forecast is as in a number of examples above, the hurdle is €350,000 as well, but the ratio of hurdle shares to non-hurdle shares is now 1:19, or 5%. The proceeds waterfall is as follows:

Below, I outline how the hurdle shares relate to the 10% test and provide an overview of the cap table for each shareholder.

The above data means that, if there is a remuneration objective, holding the hurdle shares is seen as an ‘other activity’ and the proceeds (€620,000) from it are taxed in Box 1 as income from other activities. The hurdle shares are (at least economically) a subordinated share class and they make up less than 10% of the company total, both in terms of issued capital and issued capital plus share premium. This is essentially the situation as described by the Dutch Tax Authorities. In the above example, 100% of the dividends on the hurdle shares is taxed in Box 1 with the target manager, and the exit proceeds only insofar as they exceed the purchase price paid.

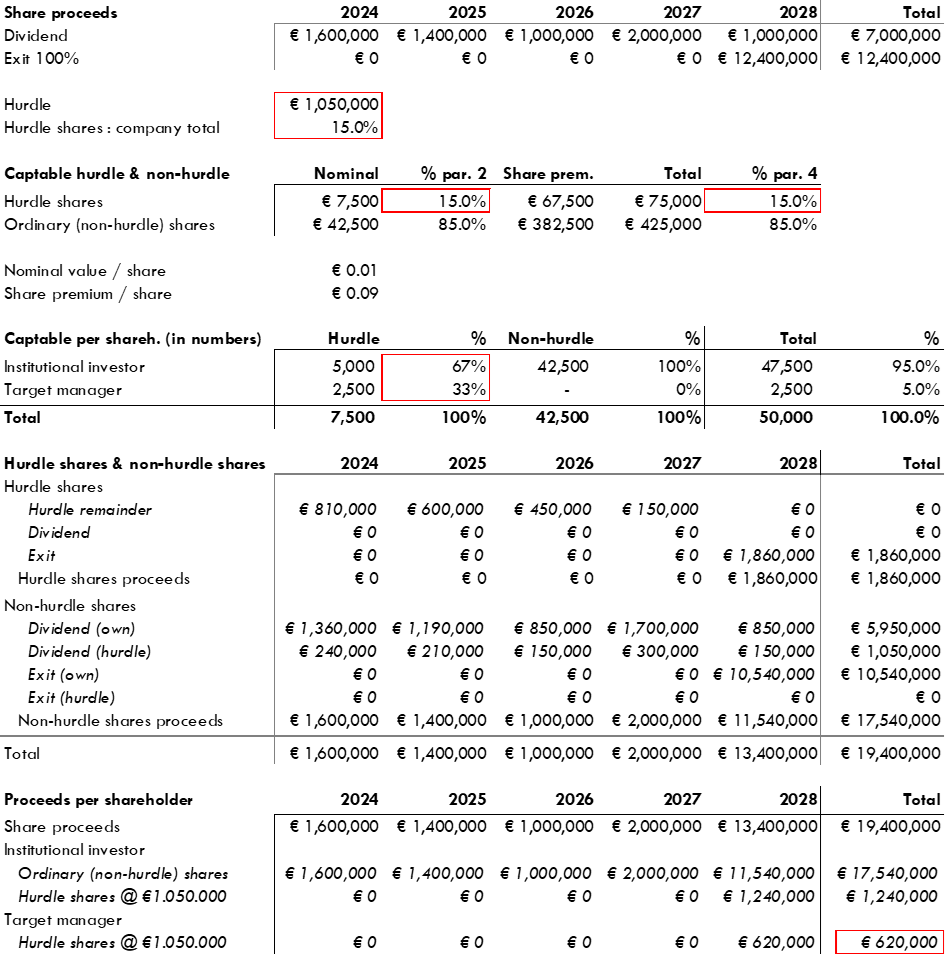

However, you can create an economically identical situation that falls outside the 10% test boundaries. How? The answer is very simple. I can adjust our sample calculation in such way that a number of the non-hurdle shares are changed into hurdle shares. It works as follows:

With these new ‘settings’ the target manager receives exactly the same in every forecast as in the previous situation, with the relevant difference that the hurdle shares grammatically fall outside the lucrative interest scheme because the 10% test has not been met.

The major shareholder also receives hurdle shares, increasing the ratio to 15%. The total hurdle amount has also tripled, as has the number of hurdle shares. However, the hurdle per share is still the same. The hurdle shares held by the major shareholder are identical to the hurdle shares held by the target manager and therefore belong to the same share class, also economically.

Should this situation happen to arise (whether temporarily or not), I don’t think the lucrative interest rule applies, as long as the situation lasts. But if the non-applicability of the lucrative interest rule was the decisive reason for this set-up, a tax inspector might try to apply the lucrative interest rule anyway by invoking the doctrine of fraus legis (abuse of law). Whether this can be demonstrated plausibly will differ from case to case due to the strong factual dependency.

Not every setup that avoids falling under the lucrative interest rule in the manner described automatically may qualify as fraus legis. This is because there may be plenty of other reasons for the emergence of such a situation. For instance, if an institutional investor intends to have more managers acquire hurdle shares and only temporarily intends to hold its own hurdle shares. As I mentioned earlier, this will strongly depend on the specific case.

Additionally, there is a possible tax-substantive argument against this structure. The ‘rights’ held by the taxpayer are economically equivalent to hurdle shares that do trigger the 10% test, which, in turn, are economically comparable/equivalent to shares as referred to in paragraph 2. However, I fear that this argument may not hold water because the legislator has chosen a mathematical approach, and the Supreme Court has declared it applicable to paragraph 4. A similar tension exists in the participation exemption of Article 13 Corporate Income Tax Act 1969, since the nominal value of shares can be easily adjusted without necessarily leading to differences in economic terms. By the way, I do not recall case law where the 5% test in the participation exemption was ignored based on fraus legis, and participation benefits were included in corporate income tax assessment.

Any questions? Please reach out!

- Unless it concerns the (much less common in practice) so-called participating preferred stock.

↩︎ - An acquisition of shares with full recognition of debt can be processed in the acquirer’s books as follows: Shares €100, to | Debt €100, while the acquisition of the same shares with a hurdle, without recognition of debt, would look as follows: Shares €20, to | Cash €20. The equity of the acquirer of the shares thus does not increase or decrease in any of the scenarios.

↩︎ - This is only different if the hurdle is covered ‘in cash’ rather than nominally. That would mean that the shares proceeds relinquished by the hurdle shareholder for the sake of the hurdle are first discounted to the acquisition date and then that amount is deducted from the hurdle.

↩︎ - That difference is calculated as follows: €1,000,000 -/- (€1,000,000 / (1+14%)^(2028 -/- 2025)).

↩︎ - This does not mean that if an employee pays a purchase price that is lower than the FMV of those shares, the difference cannot be included for wage withholding tax purposes. For contractors this can be taxed in the profit or income sphere.

↩︎ - This has been included in the wording of the law as from January 1st, 2024 and takes retroactive effect to June 26th, 2023. ↩︎