If you are interested in moving to the Netherlands and you want to know what the Dutch personal income tax (‘PIT’) consequences are in relation to your shareholdings, look no further. In this article, we will elaborate on two main themes, with various scenarios and sub-scenarios:

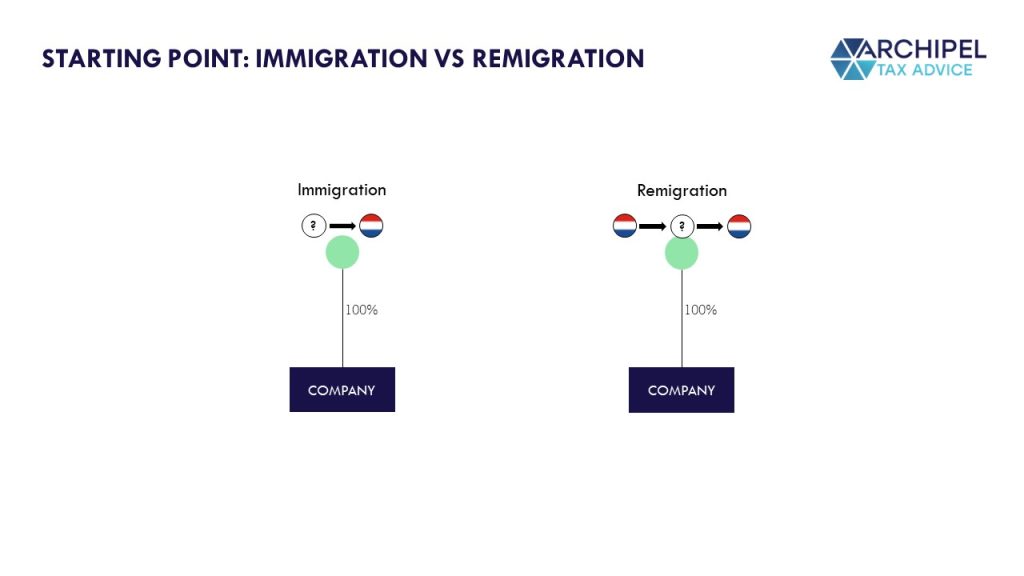

An individual with a ≥5% shareholding moves to the Netherlands (i) for the first time, or (ii) after having only temporarily lived abroad.

For my article about moving from the Netherlands (emigration) to another country, you can click this link.

But what about <5% stakes?

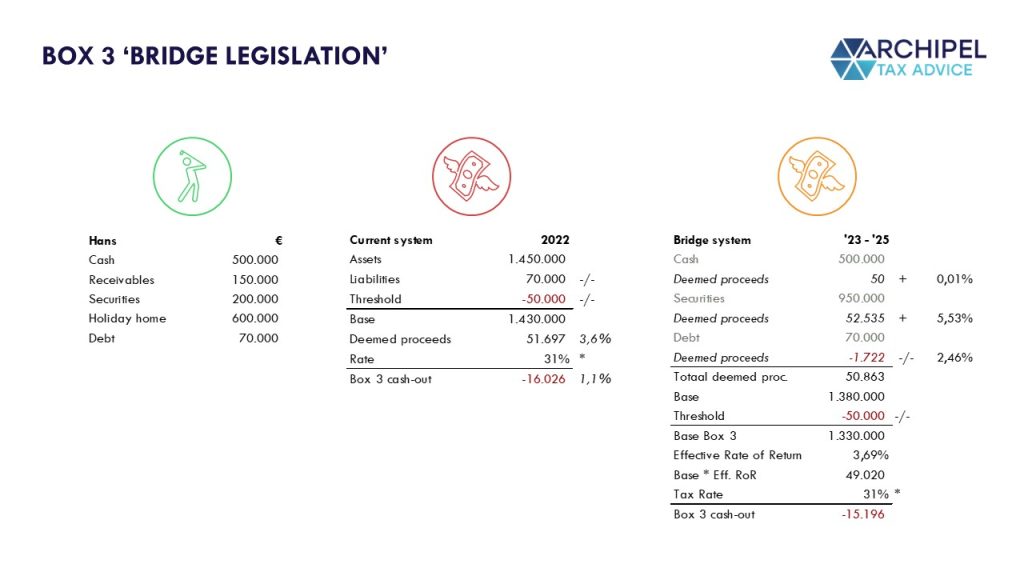

The answer is brief. The rules governing <5% stakes are fewer and simpler because those shares would generally be taxable in ‘Box 3’ of the Dutch PIT, which is an annual tax (currently 31%) on deemed returns of approx. 6% (to be determined after the tax year) on the Fair Market Value of those shares. As it stands, it’s highly likely that this system (‘bridge legislation’) will last only up to and including 2025, because it may be replaced after. Nobody knows for certain what that replacement will look like, but it’s probably going to be a tax on both realized (e.g. dividend and capital gains) and unrealized (value increase) income.[i] As this is about all that can be said of <5% stakes, we won’t delve deeper into this particular subject.

As for ≥5% stakes, the tax rules regarding immigration and remigration themes are much less complex than those that cover a move away (emigration) from the Netherlands. If you’re more interested in the latter, you can read our article here (in Dutch), in which we also touch upon when someone is considered a Dutch tax resident.

In this article, however, we assume that on the day someone physically moves to the Netherlands, that person becomes resident of the Netherlands for Dutch PIT purposes, and therefore fully liable to PIT.[ii] This applies to all scenarios described.

What’s the main fiscal difficulty in this subject matter?

You should know that in all of the themes (immigration, emigration, remigration), the main fiscal focus is always on the amount of the taxable (future) capital gain, determined in accordance with article 4.19-1 PIT Act.[iii] This is due to the fact that, generally, the Netherlands aims to tax only the shareholding’s value increase that occurred during the time in which the shareholder was liable to Dutch PIT on those shares. And other (deemed) equity proceeds like dividends, of course.

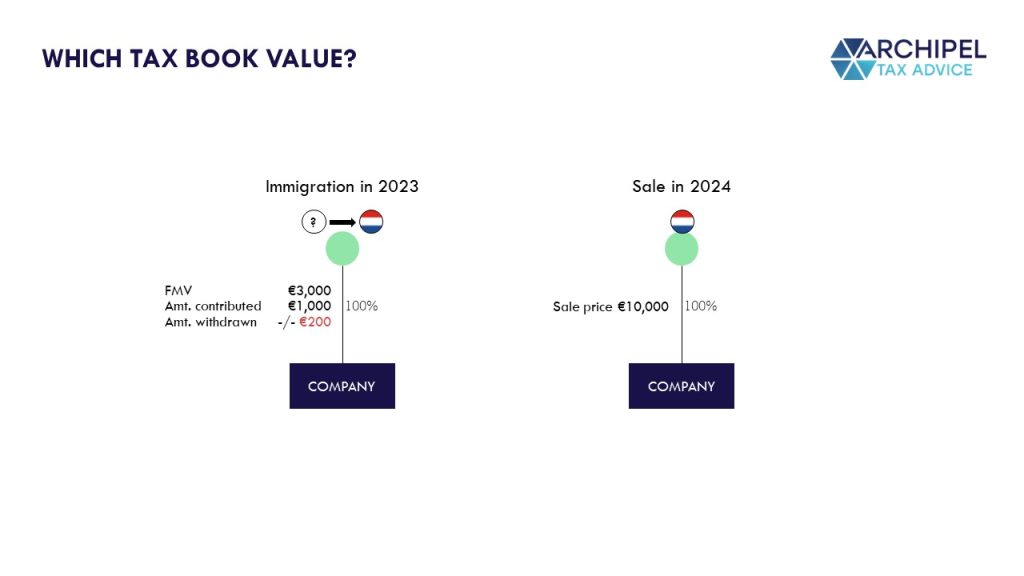

Therefore, the matter always comes down to determining (i) the correct amount of the ‘tax book value’ (“verkrijgingsprijs”) of the ≥5% shareholding, and, way more factually (and thus governed by way fewer legal provisions), (ii) the Fair Market Value (‘FMV’) of those shares at a later taxable moment.

In case the stake is held in a company that drives a business enterprise and has at least some financial history, the Dutch Tax Authorities prefer to use the ‘Enterprise Discounted Cash Flow’ (‘DCF’) method for determining the FMV, generally either at the moment someone enters the Netherlands or leaves it. If you’re interested in this particular aspect, you should read this article we wrote.

However, the main difficulty of the immigration and remigration themes rather is to determine which value to use as the tax book value: cost price (amount invested) versus FMV.

Let’s first start with the first and most straight-forward of the themes: immigration!

i) IMMIGRATION: MOVING TO THE NETHERLANDS FOR THE FIRST TIME

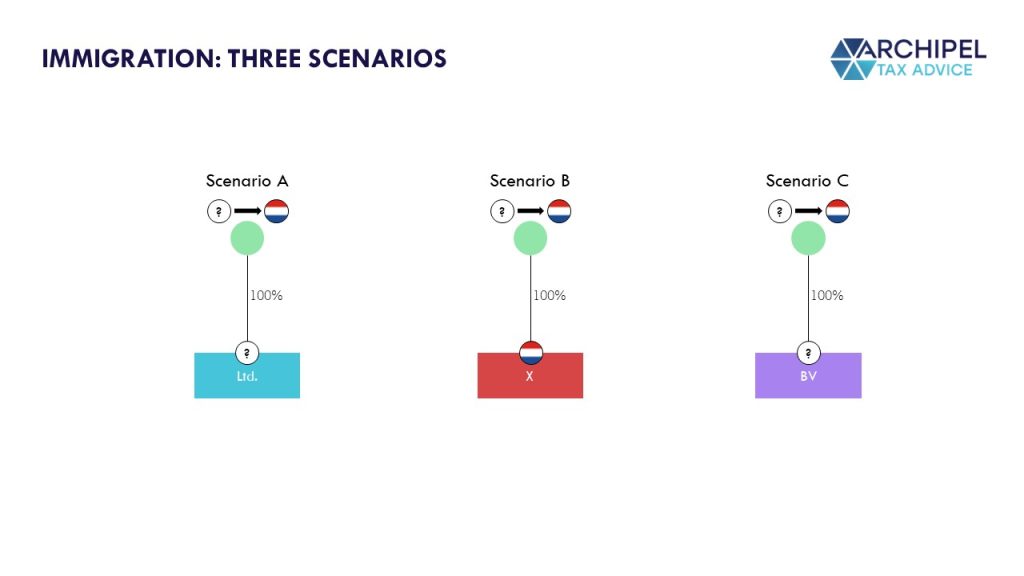

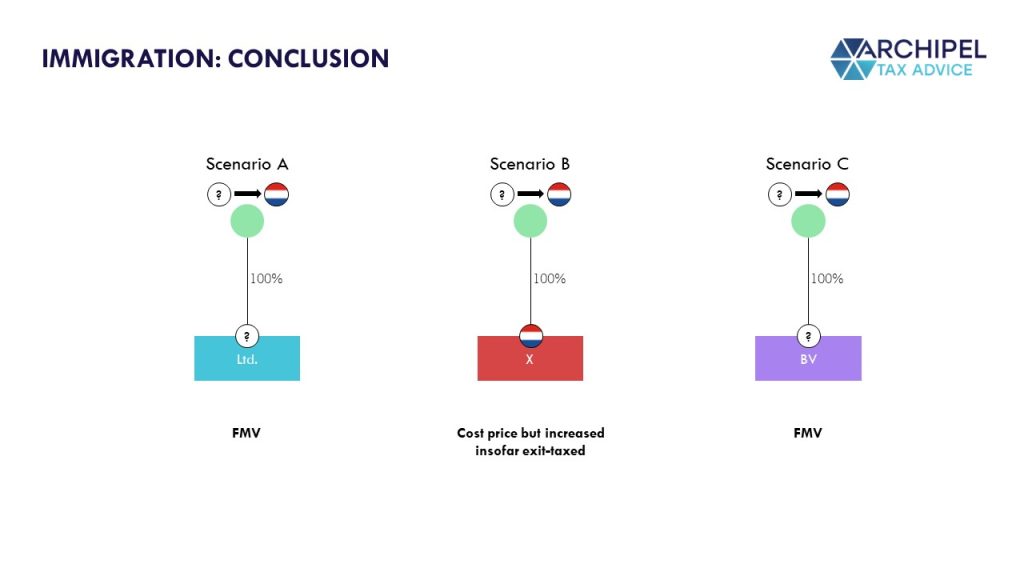

In this scenario, we can distinguish between three scenarios:

- An individual holds a ≥5% stake in a company that is neither tax resident of the Netherlands, nor incorporated under Dutch law.

- An individual holds a ≥5% stake in a company that is tax resident of the Netherlands, regardless of the laws under which it was incorporated.

- An individual holds a ≥5% stake in a company that is not a tax resident of the Netherlands, but is incorporated under Dutch law.

Scenario A: the company is neither tax resident of the Netherlands, nor incorporated under Dutch law

The individual will go from completely out-of-scope for ‘Box 2’ to fully subject to Dutch PIT. The tax book value is set at the FMV at the time of becoming a Dutch tax resident, regardless of the exit taxation rules that the other country applies.[iv] This means that the Netherlands applies a step-up or step-down, depending on the value in relation to the actual cost price.

For example, if the shareholding’s FMV has plummeted to below the total amount that the shareholder invested in it, that shareholder would have been better off in case the Netherlands took the (higher) cost price as the tax book value. Instead, the tax book value is ‘stepped down’ to the FMV. Inversely, if the shareholding’s FMV has gone up in relation to the cost price, it is fiscally beneficial for the shareholder that the Netherlands takes the FMV as the tax book value instead of the (lower) cost price, because a future capital gain on those shares will be taxed for a smaller amount.

Scenario B: the company already is an ‘actual’ tax resident of the Netherlands, regardless of its place of incorporation

In this case, the individual was already liable to non-resident PIT.[v] That person will only shift from partly liable to PIT to fully liable to PIT. Pursuant to the main rule[vi] the capital gain for a non-resident individual (i.e. pre-immigration) is calculated in accordance with the same rules that apply to resident individuals. However, immigration -other than emigration- does not trigger a (deemed) taxable capital gain.

The main question is: what happens to the tax book value when that person shifts from limited to full PIT liability? The answer lies in article 4.25-3 PIT Act[vii], pursuant to which the tax book value is not automatically stepped up to the FMV, because the Netherlands have a claim to the value increase that occurred also during the time that the individual was non-resident but liable to PIT.[viii]

Further rules regarding the tax book value can be found in the Income Tax Implementation Decree (‘Decree’).[ix] The Decree stipulates[x] that the tax book value is determined by the cost price[xi] in this case. However, a step-up is provided to the FMV to the extent that the shareholder was ‘exit-taxed’ thereon by the other country.[xii]

Please note that if that company was incorporated in the other country, but moved its ‘place of effective management’ to the Netherlands prior to the individual’s immigration (e.g. year 0), that individual at that time (of becoming liable to non-resident PIT, year 0) did not receive a step-up or step-down, even though the value increase (in relation to the cost price) occurred during the time that that person had no link with the Netherlands. This is in contravention of the general principal that the Netherlands only taxes the incremental value during the Dutch-taxed time, but it appears that this specific situation was simply not taken into account. However, when the individual subsequently (e.g. year 1) moves to the Netherlands, the FMV at year 0 is taken into account anyway.[xiii] The FMV at year 1 is only taken into account to the extent that the individual was exit-taxed thereon (please note what I described above).

Scenario C: the company is not a tax resident of the Netherlands, but is incorporated under Dutch law

This is a delicate matter, because the Dutch law incorporation may trigger several provisions pursuant to which the company is considered to be a Dutch tax resident (i.e. fictitiously) for certain purposes, aimed at securing the taxation rights of the Netherlands.

For example, if a company is incorporated under Dutch law, it will be considered to be a Dutch tax resident for purposes of section 4.6 of the PIT Act, which encompasses articles 4.16 – 4.35.[xiv]

Notwithstanding this fiction, the individual was in principle not liable to non-resident PIT before immigration.[xv] And because of that, the main rule[xvi] for individuals moving to the Netherlands applies, which says that the tax book value should be the FMV, regardless of whether the individual was ‘exit-taxed’ by the other country. In other words, also in this scenario the Netherlands provide a step-up or step-down.

Conclusion for immigration: moving to the Netherlands for the first time

| A No previous NL link | B Company already was actual NL tax resident | C Company was only incorporated under NL law | ||||||||

| Tax book value | FMV | Cost price, but increased insofar exit-taxed | FMV |

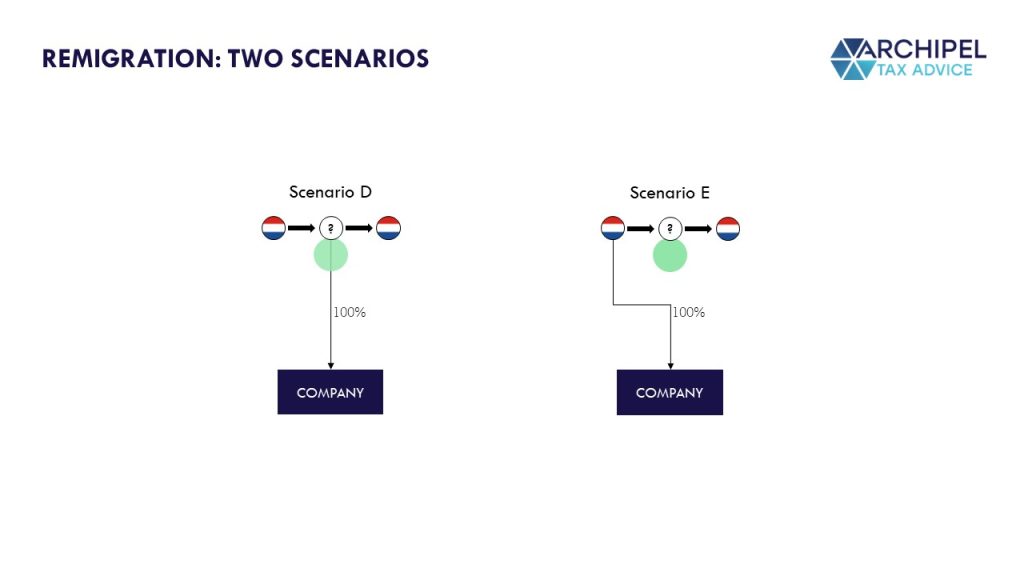

II) REMIGRATION: MOVING TO THE NETHERLANDS AGAIN

This is where it can become a little bit less straight-forward, because of the former residency link with the Netherlands. It may be helpful to first read our article on ‘emigration’ before continuing from here.

We can distinguish between the following remigration scenarios:

- An individual has acquired a ≥5% stake in a company during the time that that person was not a Dutch tax resident.

- An individual had previously left the Netherlands already owning a ≥5% stake in a company.

Scenario D: the individual acquired the company shares during that person’s time abroad

In this scenario, we can further distinguish between the following sub-scenarios:

D.1 The company is not a Dutch tax resident.

D.2 The company is a Dutch tax resident.

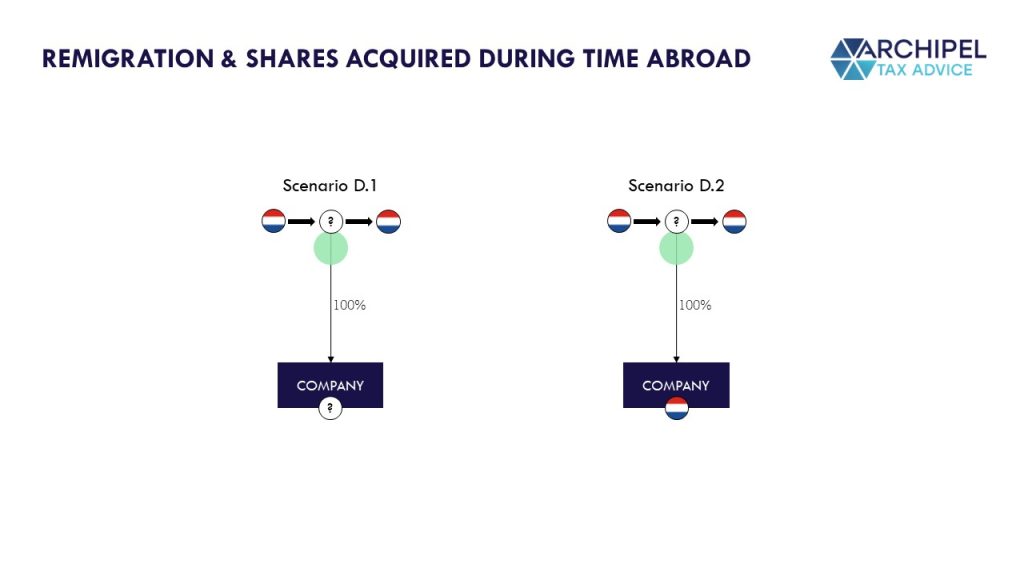

Scenario D.1: the individual acquired the foreign company shares during that person’s time abroad

In case the company was not (considered) a tax resident of the Netherlands at the time of acquisition, you’re probably inclined to think that, similar to Scenario A, the tax book value of the shares would be set at the FMV following the same rule. After all, the ‘remigrant’, at the moment just before remigration, is as out-of-scope for Dutch PIT as the Scenario A immigrant.

Although your gut ‘FMV-feeling’ is right, the rule that governs Scenario A is not applicable here, merely because the individual has lived in the Netherlands before.[xvii]

The Decree dictates what the tax book value is set at in this case.[xviii] Regardless of whether the other country levies an exit tax, the Netherlands will take the FMV at the time of remigration as tax book value.[xix] So in the end, this is the same result as in Scenario A, albeit through another path.

Scenario D.2: the individual acquired the Dutch company shares during that person’s time abroad

In case the company was (considered) a tax resident of the Netherlands at the time of acquisition, that person became liable to non-resident PIT at that same moment. The cost price is set as the tax book value as from that moment until remigration.[xx] The moment that the individual remigrates (moves to the Netherlands again), that person will shift from limited to full PIT liability. Therefore, it looks a lot like Scenario B.

And in this case, the tax book value follows the exact same rules! So upon remigration the tax book value as set at the cost price and is increased only to the extent that the individual was ‘exit-taxed’ by the other country.

Scenario E: the individual acquired the company shares before that person’s (previous) emigration

The tax consequences in this scenario vary greatly depending on whether that person, at the time of remigration, is still required to pay tax in relation to a Protective Tax Assessment (in Dutch: ‘conserverende aanslag’, hereinafter: ‘PTA’) in relation to the ≥5% stake. We refer to our other article for more info thereon. We can distinguish between the following:

E.1 There is no PTA at the time of remigration.

E.2 There is a PTA in relation to the ≥5% stake that still needs to be paid at the time of remigration.

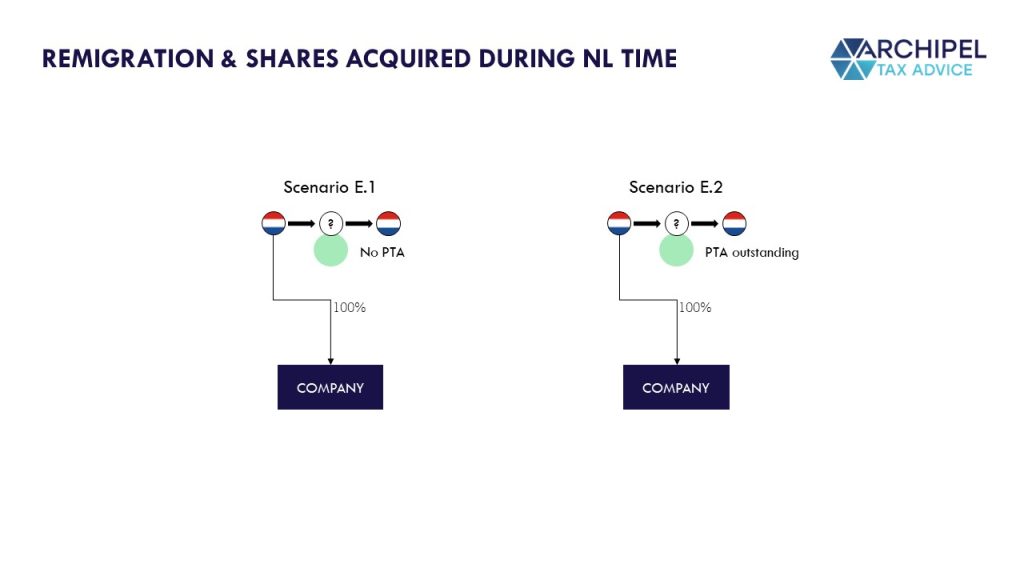

Scenario E.1: there is no PTA

Regardless of whether the company is a Dutch tax resident, the individual’s shareholding’s tax book value is governed by the Decree[xxi], which says that the starting point is the cost price. From this point on, the tax treatment is very similar to Scenario D.1 in case of a foreign company (FMV), and similar to D.2 in case of a Dutch tax resident company.

The tax book value is affected to the extent that the value change occurred during the time in which the individual was not liable to Dutch PIT on those shares, or to the extent that the individual was ‘exit-taxed’ by the other country on a value higher than the cost price.

This means that it does matter whether the company is considered a Dutch tax resident, because if it is, the individual was liable to non-resident PIT, pursuant to which the tax book value can only be affected by an exit taxation in the other country.

Scenario E.2: there is a PTA in relation to the shares

This scenario implies generally that the individual, when that person first left the Netherlands, held a ≥5% stake in a company, either Dutch or foreign. Again, for the tax aspects regarding such ‘emigration’, we recommend you read this article.

If the FMV of that shareholding exceeds the tax book value at the moment of emigration, the difference is taxable as a capital gain because the individual is deemed to have sold the shareholding upon emigration. This deemed capital gain is automatically taxed by way of a PTA, which is initially not so different from a regular PIT assessment. However, the collection of the PTA tax is deferred indefinitely (no request needed in case of intra-EU/EEA emigration). The PTA tax is collected instantly if the individual transfers (part of) the shares, or it is collected for the amount of the ‘Box 2’ PIT amount on any dividends received on those shares.

In this scenario, therefore, the individual has not transferred the shares post-emigration, nor has the individual received (sufficient) dividends for the PTA to be completely collected. In other words: (part of) the PTA is still outstanding.

Looking at the PIT Act, the main rule of article 4.25-1 is not applicable here, because both the exceptions of article 4.25-3 and 4.25-4 apply. Instead, we get directed to the Decree for the determination of the tax book value as well as that of the amount of the PTA itself.

What we find is that the PTA itself is waived for the total outstanding amount.[xxii] From the Dutch point of view, this is sensible if the Netherlands don’t lose out on a prior tax claim. And that appears to be the case, because the tax book value follows the Decree rules, starting from the cost price and potentially increased if the individual was exit-taxed on a higher value by the other country. If the other country did not levy an exit tax on some higher FMV, then the tax book value is increased with only the costs incurred in relation to the pledge/guarantee (which wasn’t required unless the individual emigrated to outside the EU/EEA).[xxiii]

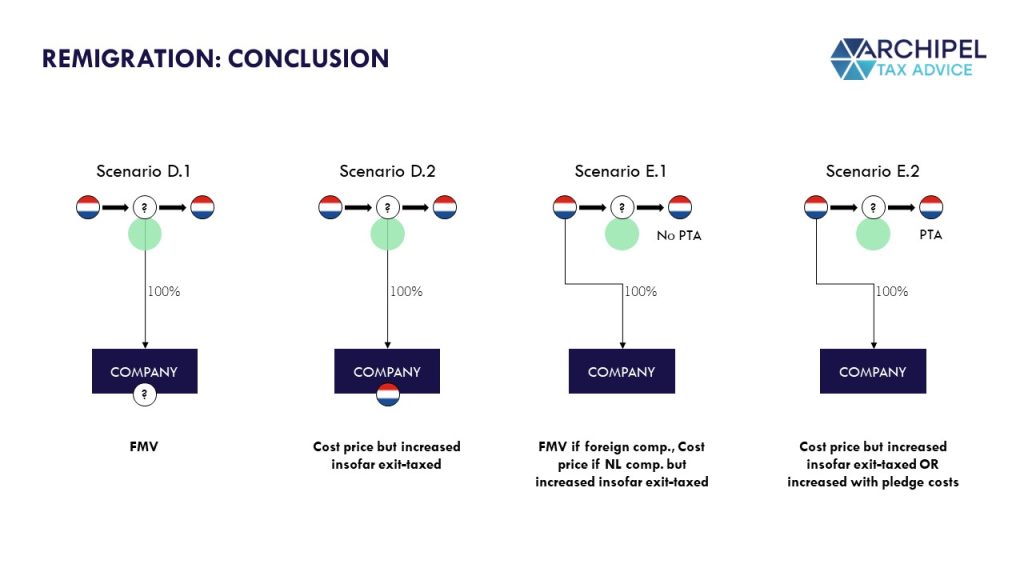

Conclusion for remigration: moving to the Netherlands again

| D.1 Foreign comp. shares acquired during time abroad | D.2 Dutch company shares acquired during time abroad | E.1 Shares acquired before emigration, but no PTA | E.2 Shares acquired before emigration, PTA outstanding | |||||||||

| Tax book value | FMV | Cost price, but increased insofar exit-taxed | FMV if foreign company; Cost price if NL company but increased insofar exit-taxed | Cost price, but increased insofar exit-taxed OR increased with pledge/guarantee costs | ||||||||

| PTA | n/a | n/a | n/a | Waived |

Other scenarios

There are various other scenarios that involve shifts in the place of the company’s effective management, and therefore a shift in the company’s residence from a Dutch tax perspective. Furthermore, there’s a special rule for non-Dutch individuals that come to live in the Netherlands for fewer than eight years. In this article we don’t elaborate on those scenarios, however, because those are less common.

Need help?

Please reach out if you’re a ≥5% shareholder and are contemplating moving to or from the Netherlands. This subject matter can get murky really quickly, and case-specific details may cause your situation to relevantly deviate from the scenarios that we describe in this article. Happy to discuss.

And again: for my article about moving from the Netherlands (emigration) to another country, you can click this link.

[ii] Article 2-1-a PIT Act: “Belastingplichtigen voor de inkomstenbelasting zijn de natuurlijke personen die […] in Nederland wonen (binnenlandse belastingplichtigen) […].“ (link).

[iii] Article 4.19-1 PIT Act: “De vervreemdingsvoordelen worden gesteld op de overdrachtsprijs verminderd met de verkrijgingsprijs. In geval van vervreemding van een gedeelte van de in aandelen of winstbewijzen besloten rechten wordt een evenredig gedeelte van de verkrijgingsprijs in aanmerking genomen.” (link).

[iv] Article 4.25-1 PIT Act:“Indien een belastingplichtige in Nederland gaat wonen en hij op dat tijdstip aandelen in of winstbewijzen van een vennootschap heeft, wordt de verkrijgingsprijs van die aandelen of die winstbewijzen gesteld op de waarde die op dat tijdstip in het economische verkeer aan die aandelen of die winstbewijzen kan worden toegekend.” (link).

[v] Article 2.1-b: “Belastingplichtigen voor de inkomstenbelasting zijn de natuurlijke personen die […] niet in Nederland wonen maar wel Nederlands inkomen genieten (buitenlandse belastingplichtigen).” (link) & article 7.1-b PIT Act: “Ten aanzien van de buitenlandse belastingplichtige wordt de inkomstenbelasting geheven over het door hem in het kalenderjaar genoten […] belastbare inkomen uit aanmerkelijk belang in een in Nederland gevestigde vennootschap […].” (link).

[vi] Article 7.5-1 PIT Act: “Het belastbare inkomen uit aanmerkelijk belang in een in Nederland gevestigde vennootschap is het inkomen uit een niet tot het vermogen van een onderneming behorend aanmerkelijk belang in een in Nederland gevestigde vennootschap […] berekend volgens de regels van hoofdstuk 4 […].“ (link).

[vii] Article 4.25-3 PIT Act: “Het eerste lid is voorts niet van toepassing indien de belastingplichtige voordien ten aanzien van een aanmerkelijk belang buitenlands belastingplichtig is geweest.” (link) which refers to article 4.25-1 PIT Act.

[viii] Memorie van Toelichting (Belastingherziening 2001), Kamerstukken II 1998-1999, 26727, nr. 3, p. 213-214.

[ix] Article 4.25-4 PIT Act: ”Bij algemene maatregel van bestuur kunnen regels worden gesteld inzake de verkrijgingsprijs voor de gevallen bedoeld in het tweede en derde lid.” (link).

[x] Article 16-1 Decree: “Indien een belastingplichtige met een aanmerkelijk belang in Nederland gaat wonen en de belastingplichtige eerder in Nederland heeft gewoond of voordien ten aanzien van een aanmerkelijk belang buitenlands belastingplichtig is geweest, wordt de verkrijgingsprijs van de tot dat belang behorende aandelen of winstbewijzen gesteld op de verkrijgingsprijs, bedoeld in artikel 4.21 van de wet, en vervolgens vermeerderd of verminderd zoals in de volgende leden is aangegeven.” (link).

[xi] Article 4.21-1 PIT Act: “Onder verkrijgingsprijs wordt verstaan de tegenprestatie bij de verkrijging vermeerderd met de ten laste van de verkrijger gekomen kosten.” (link).

[xii] Article 16-2 Decree: “De verkrijgingsprijs volgens artikel 4.21 van de wet wordt vermeerderd met de waardeaangroei van de aandelen of winstbewijzen boven die verkrijgingsprijs voorzover blijkt dat de belastingplichtige in verband met het gaan wonen in Nederland in het buitenland hierover een naar het inkomen geheven belasting heeft betaald die naar Nederlandse maatstaven redelijk is.” (link).

[xiii] Articles 4.25-3, 4.25-4 PIT Act & articles 16-1, 16-3 Decree. The latter provision: “De verkrijgingsprijs volgens artikel 4.21 van de wet wordt vermeerderd met de waardeaangroei van de aandelen of winstbewijzen boven die verkrijgingsprijs voorzover deze aangroei blijkt te zijn ontstaan in een periode dat de belastingplichtige ter zake van die aandelen of winstbewijzen in Nederland niet belastingplichtig was en deze waardeaangroei nog niet is begrepen in de vermeerdering van de verkrijgingsprijs ingevolge het tweede lid.” (link). The mirror provision for value decreases is in article 16-4 Decree: “De verkrijgingsprijs volgens artikel 4.21 van de wet wordt verminderd met de waardedaling van de aandelen of winstbewijzen beneden die verkrijgingsprijs voorzover deze waardedaling is ontstaan in een periode waarin de belastingplichtige ter zake van die aandelen of winstbewijzen niet in Nederland belastingplichtig was.” (same link).

[xiv] Article 4.35 PIT Act: “Voor de toepassing van deze afdeling wordt een lichaam waarvan de oprichting heeft plaatsgevonden naar Nederlands recht steeds geacht in Nederland te zijn gevestigd.” (link).

[xv] Article 7.5 PIT Act already has its own deemed residency provision. Even though article 7.5-1 PIT Act mentions that the taxable income is determined in accordance with the entire chapter 4 PIT Act (i.e. including article 4.35), it is illogical to assume that the fiction of 4.35 PIT Act would apply within the domain of article 7.5 PIT Act, especially since the language of article 4.25-3 would otherwise be redundant / obsolete.

[xvi] Article 4.25-1 PIT Act.

[xvii] Article 4.25-2 PIT Act: “Het eerste lid is niet van toepassing indien de belastingplichtige voordien is opgehouden in Nederland te wonen.” (link).

[xviii] Article 4.25-4 PIT Act & article 16 Decree.

[xix] Article 16-2, 16-3 and 16-4 Decree.

[xx] Article 7.5-1 PIT Act & article 4.21-1 PIT Act.

[xxi] Article 4.25-2, 4.25-3 and 4.25-4 PIT Act.

[xxii] Article 4.25-5 PIT Act: “Bij algemene maatregel van bestuur kunnen tevens regels worden gesteld met betrekking tot het verminderen van de belastingaanslag bij de vaststelling waarvan artikel 4.16, eerste lid, onderdeel h, of artikel 7.5, zevende lid, is toegepast, in geval van terugkeer van de belastingplichtige naar Nederland voordat die belastingaanslag volledig is voldaan.” (link) & article 16-5 Decree: “Indien artikel 4.16, eerste lid, onderdeel h, onderscheidenlijk artikel 7.5, zevende lid, van de wet eerder met betrekking tot het aanmerkelijk belang van toepassing is geweest, wordt de belastingaanslag over het jaar bij de vaststelling waarvan een van de genoemde artikelonderdelen van toepassing is geweest, verminderd met een bedrag dat overeenkomt met dat gedeelte van de belasting waarvoor krachtens artikel 25, achtste lid, van de Invorderingswet 1990 nog uitstel van betaling loopt. Met betrekking tot deze vermindering is artikel 30g, tweede lid, van de Algemene wet inzake rijksbelastingen niet van toepassing.” (link).

[xxiii] Article 16-6 Decree: “De verkrijgingsprijs volgens artikel 4.21 van de wet van de nog tot het aanmerkelijk belang behorende aandelen of winstbewijzen wordt vermeerderd met de aan die aandelen of winstbewijzen toe te rekenen kosten welke zijn gemaakt voor het stellen van zekerheid als bedoeld in artikel 25, achtste lid, van de Invorderingswet 1990, tenzij de verkrijgingsprijs op grond van het tweede lid reeds is vermeerderd met de waardeaangroei van de aandelen of winstbewijzen die eerder krachtens artikel 4.16, eerste lid, onderdeel h, onderscheidenlijk artikel 7.5, zevende lid, van de wet tot het belastbare inkomen uit aanmerkelijk belang is gerekend.” (link)