You may have heard about EU Tax Law, but what is it exactly? Aren’t the EU Member States independent countries with their own direct tax systems? Yes, they are, and the sole responsibility of direct taxes, such as personal income tax and corporate income tax, remains with the Member States. So what role does European Tax Law play exactly in the field of direct taxation? This article provides a crash course in European Tax Law.

National Law versus EU Law

As indicated in the introduction, the EU Member States are all independent countries with their own legal system. This means that all EU rules must be implemented into the national law system. The European Law system is build out of primary EU law and secondary EU law. Primary EU law follows from The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU“). Secondary EU law consists of directives on specific topics (for example, the EU Green Deal: fit for 55).

Primary EU Law: fundamental freedoms and State Aid

The TFEU describes how the EU should function and contains some general legal concepts that are relevant for tax laws. These are called the fundamental freedoms. The TFEU in that respect should be viewed as the EU constitution. National tax laws of the EU Member States must be compatible with the TFEU. The most important concepts are:

- The freedom of movement for workers (article 45 TFEU)

- The freedom of establishment (article 49 TFEU)

- The freedom of capital (article 63 TFEU)

- The prohibition to distort free competition by granting State Aid (article 107 TFEU and article 108 TFEU)

As indicated above, national tax law of the EU Member States must be compatible with the TFEU.

For example, the fundamental freedom “freedom of establishment”, is directed to ensuring that foreign nationals and companies are treated the same way as nationals of that State. This means that foreign companies may not be subjected to a higher tax than national companies of the respective EU Member State in question, provided that the companies are in a comparable position according to the purpose of the rule in question.

If a tax payer finds that a national provision of tax law is in breach with the fundamental freedoms, a legal procedure can be started or a complaint can be filed with the European Commission.

Apart from the fundamental freedoms (listed under a, b, c and d), the TFEU prohibits illegal State Aid. In principle, this is the legal area of competition law, but it also prohibits the EU Member States to distort competition by favoring national tax payers through selective tax benefits. The European Commission monitors illegal State Aid, while anyone can make a complaint with the European Commission about illegal State Aid Schemes (even non-Europeans).

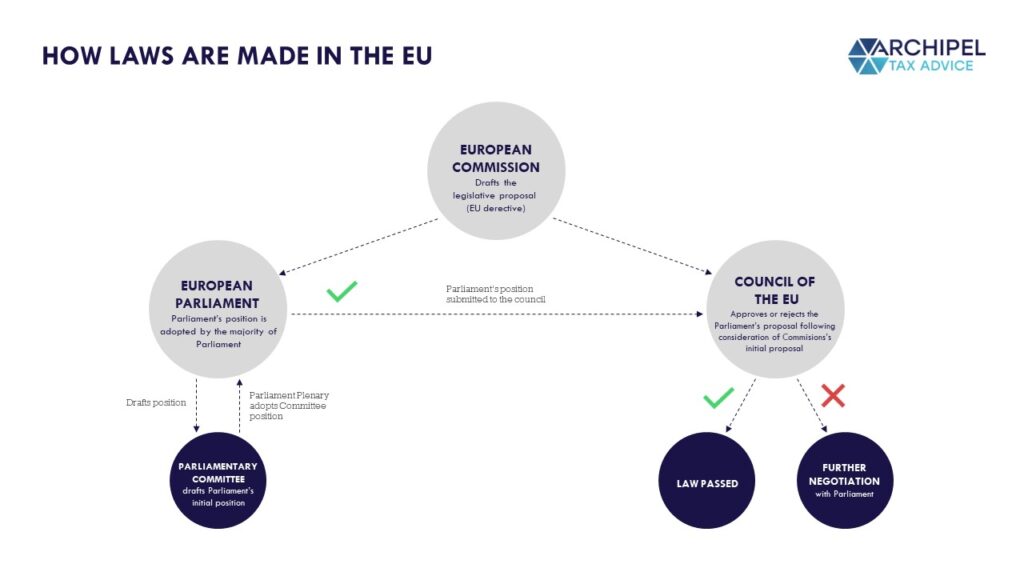

Secondary EU Law: the EU directives

Secondary EU Law consists of the EU directives, in this case tax directives. The tax directives are generally proposed by the European Commission and must then be adopted by the Council of the EU. The EU Parliament is consulted in the process.

Once adopted, a directive must be implemented into national law of the EU Member States. The implementation must be in line with the boundaries provided in the directive.

The most important EU direct tax directives are:

- The Parent-Subsidiary Directive

- The Interest and Royalty Directive

- The Merger Directive

- The Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (1 and 2)

The Parent-Subsidiary Directive provides for an exemption of both withholding tax and corporate income tax of intra-group dividends. The minimum shareholding % to qualify as a group is 10%, but Member States can also allow lower interest (such as 5% in the Netherlands). The parent-subsidiary directive also contains an anti-abuse provision, on which basis the benefits of the directive must be denied in abusive situations (for example, this Dutch case – FYI: it’s in Dutch).

The Interest and Royalties Directive provides for a withholding tax exemption on royalties and interest if the participation (direct or indirect) equals at least 25% during a minimum period of 1 year. This directive also provides for an anti-abuse measure.

The Merger Directive aims to remove fiscal obstacles to cross-border reorganizations involving companies in two or more Member States. In the case of mergers and divisions, the transferring company transfers assets and liabilities to one or more receiving companies. The Merger Directive provides for deferral of the taxes that could be charged on the difference between the real value of such assets and liabilities and their value for tax purposes. The deferral is granted provided that the receiving company continues with their tax values and effectively connects them to its own permanent establishment in the Member State of the transferring company.

The Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (“ATAD”) 1 and 2 oblige the Member States to prevent tax avoidance to the implementation of:

- Interest deduction limitation rule (EBITDA rule)

- Exit taxation rules

- General Anti-Avoidance Rule (“GAAR”)

- Controlled Foreign Company rules

- Anti-Hybrid rules

Next to the direct tax directives, the EU has also adopted VAT and Customs legislation. For example: the VAT Directive, which obviously constitutes indirect taxation, is fully harmonized. This means that all EU Member states are obliged to levy VAT according to the VAT Directive.

The EU Institutions: how laws are made

The most relevant EU institution for European tax law are the:

- European Commission

- European Parliament

- Council of the EU

- EU Court of Justice

European Commission

The biggest power of the European Commission is that it has the right of initiative. This means that the European Commission has the right to propose new tax directives. The European Commission also enforces EU legislation, meaning that it monitors if the EU Member States don’t distort free trade and competition (for example by monitoring illegal State Aid schemes of national institutions). Next to that, the Commission can issue tax policies.

The European Commission is also in charge of the EU budget and represents the EU to third countries, but these functions are not necessarily related to EU tax law.

The European Parliament

The European Parliament is the EU’s only directly-elected institution. In relation to tax law, the main function of the Parliament is to consult on proposals made by the European Commission. Both the Council and the Parliament have an indirect right of initiative as they can request a legislative proposal from the Commission.

Not really tax related, but an important role: the Commission President is elected for a 5-year term by the European Parliament, following the European elections.

The Council of the EU

The Council of the EU also has to vote for new legislation in the direct tax area. Each Member State delegates the relevant Minster that has a seat in the Council. For tax matters, these are usually the ministers of finance. There are a number of policy areas in which the Council has to vote unanimously, which includes direct tax matters. This means that each Member State has a veto right in relation to direct tax matters. In practice this usually means that the Member State in question brings forward its objections to a proposal and that (small) amendments are made to satisfy this State.

Both the Council and the Parliament have an indirect right of initiative as they can request a legislative proposal from the Commission,

The presidency of the Council rotates among the EU member states every 6 months. The presidency can influence the agenda, meaning that in some presidency there is extra attention for tax matters.

The EU Court of Justice

The most important role of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is interpreting EU law to make sure it is applied in the same way in all EU countries. The CJEU also settles legal disputes between national governments and EU institutions.

If a tax payer finds a national law in breach with either primary EU law or secondary EU law, the tax payer should first complain with the national court(s) in the EU Member State in question. The Supreme Court of said EU Member State can then, in such procedure, ask the CJEU to rule how EU law should be interpreted.

As already referred to under the “freedom of establishment”, foreign companies or shareholders may not be subject to a higher tax than national companies of the respective EU Member State, provided that the companies are in a comparable position according to the purpose of the rule in question. If the complainant finds that the rule in question is discriminator to foreign companies, the Supreme Court of the EU Member State should ask the CJEU if it finds the litigious law in breach with EU law. The CJEU provides for a binding ruling and is therefore the highest court in the EU. The CJEU plays a crucial role in enforcing EU law.

The CJEU can also sanction or force other EU institutions to take action.

Questions? Book a spot below – it’s on us!