What’s happening?

On the 22th of December, the European Commission (hereinafter: ‘EC’) has presented an initiative to combat the misuse of shell entities for improper tax purposes (‘ATAD 3’). This proposal will ensure that shell companies in the EU with no- or minimal economic activity are unable to benefit from any tax advantages, consequently discouraging their use. Furthermore, the Commission Ter Haar published a report on ‘doorstroomvennootschappen’ in the Netherlands last October.

Shell companies can be used for aggressive tax planning or tax evasion purposes. Businesses can direct financial ‘flows’ through these shell entities towards tax friendly jurisdictions. Similar with this, some individuals can use shell entities to shield assets – more specific real estate – from taxes, either in their respective home country or in the country where the property is located. The main purpose of this proposal is therefore to address the abusive use of so-called shell companies, being referred to as legal entities with no, or only minimal, substance and economic activity.

History intermediary holding companies

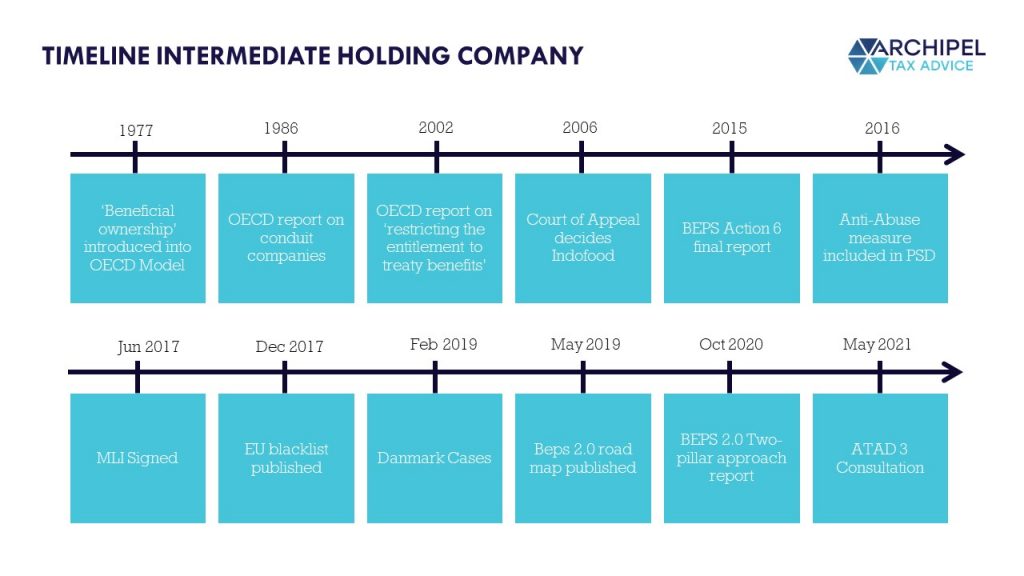

International groups often use intermediate holding companies to hold shares in subsidiaries organized on a regional or divisional basis. Furthermore, holding companies are often used as the vehicle for investing in portfolio companies in a private equity context. In past times, it was not particularly controversial that holding companies were entitled to the potential benefits of tax treaties and potential directives in their country of residence. This would frequently restrict the right of investee jurisdictions to tax dividends and gains derived by the holding company from its local subsidiaries. As shown in the timeline underneath, the perception and position of these companies has changed, with an accumulation of measures that potentially restrict the access to the benefits and directives.

This all started with the introduction of the term “beneficial ownership” into the OECD’s Model Tax Convention in 1977. The question was asked: who does actually benefit from this/these payment(s)? Whilst being slightly controversial in the 70’s, the term now appears in most tax treaties and intents to prevent treaty shopping by ensuring that the benefits of the dividends, royalties and interest articles are only accessible to residents of the contracting state that are the beneficial owners of the payment. After this, the OECD’s report on the use of conduit companies in 1986 ruled conduit companies out of the beneficial ownership regard. Nevertheless, there was no generally agreed definition of the term ‘beneficial ownership’ in tax treaties and the interpretation would follow the domestic law of the contracting states. The first hint of an international fiscal meaning of this term stems from the Indofood case (Indofood International Finance Ltd. V JP Morgan Chase Bank NA, 2006). To prevent falling foul of the beneficial ownership test, certain groups reviewed their holding structure(s) and looked to eliminate fully back-to-back financing arrangements. Furthermore, some structures which involved payment chains were set up with an “equity gap”. These structures reflected a widespread view that beneficial ownership was an objective test that was indifferent to the motives behind these holding company arrangements.

Whilst having a long history, reverting back to said changes in the OECD model treaty in the 70’s, the real challenge to the treaty status of holding companies began in 2015, when the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting project (‘BEPS’) recommended measures to restrict inappropriate usage of tax treaties. The bar is consequently set higher and higher for the criteria that holding companies need to meet in order to benefit from relief from withholding taxes and exemptions to non-resident capital gains tax. The high apex for this approach is the just published proposal to end the misuse of shell entities. Some of the statements suggest that it may never be appropriate for an intermediate holding company (using the term ‘shell entity’) to benefit from reductions in withholding taxes under tax treaties and EU directives.

The Dutch government already set up a commission that investigated the use of the so-called shell companies and their potential misuse of the Dutch tax system. This report was published last October.

Dutch investigation on shell companies (Commission Ter Haar)

‘Doorstroomvennootschappen’ (as they’re often referred to in Dutch) provide little benefit to the Dutch economy, disadvantage developing countries disproportionately through loss of tax revenue for developing countries in particular, and the phenomenon damages the reputation of the Netherlands. These are the main conclusions of the Committee on Flow-through Companies, chaired by Mr. Ter Haar, which presented its final report recently.

The committee describes the relevant components of the Dutch tax system that, at least until recently, have made the Netherlands attractive to flow-through companies. These include the participation exemption, the extensive treaty network, the absence of a withholding tax on interest and royalties and the ruling practice. The report describes examples of unintended use of each of these aspects of the Dutch tax system. In combination with the well-organized financial advice and services sector, this has led, according to the Committee, to a sizeable financial flow. The Committee believes that the measures already taken are expected to put an end to (part of) the tax-driven flow of interest and royalties. This does not mean that the Netherlands should be expected to lose its position as a country of establishment for empty holding companies, even though the Dutch tax system is no longer unique compared to other countries. According to the Committee there will still be a large group of (almost) empty conduits that make use of the Dutch tax infrastructure, whose contribution to the economy is small. The Committee therefore recommends further steps, but at the same time sees that far-reaching unilateral measures do not immediately offer a solution. In the first place, the Committee recommends a proactive attitude and a pioneering role with respect to international and European initiatives. These include the revision of the international tax system within the Inclusive Framework of the OECD and the announced EU Directive proposal on flow-through companies. According to the committee, the Netherlands should advocate measures that involve both the targeted exchange of information and to limit the benefits of the Interest and Royalties Directive and the Parent-Subsidiary Directive.

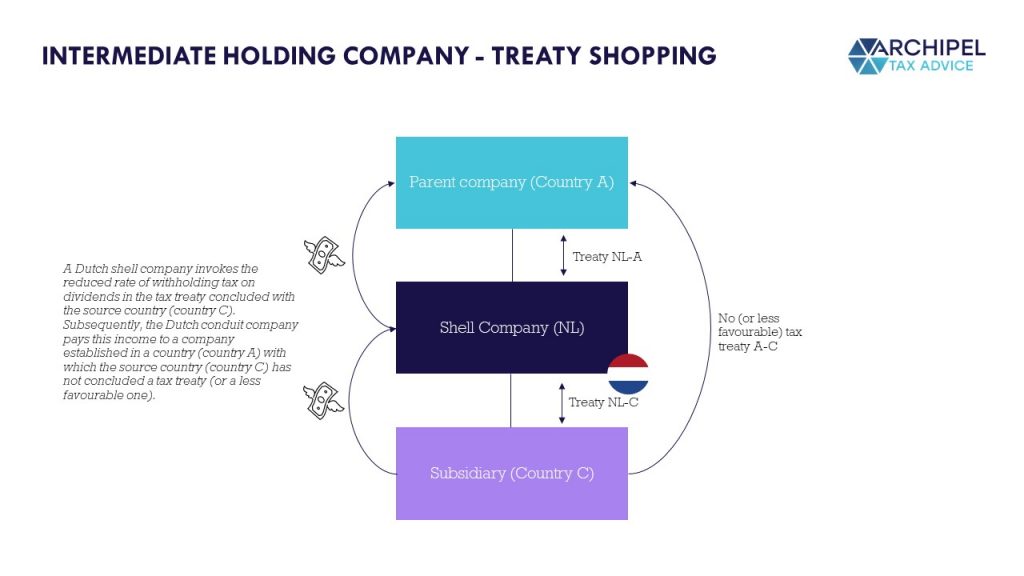

The advantage of this structure is that the dividends, by making use of the Dutch treaty network, without or with reduced withholding of local tax, arrive at the company in the country of residence (Country A), without or with reduced withholding of local tax, compared to the situation where the payment is made directly to the country of residence (Country A) by the source country (Country C). This is just one example of a (flow-through) structure in which the Dutch treaty network plays a role, in combination with the participation exemption and the dividend withholding tax exemption in treaty situations.

Because the Netherlands has long had a large bilateral tax treaty network, the Netherlands is an attractive country for ‘treaty shopping’. When the tax treaties are concluded, it is assumed that it is up to the source country to prevent the reduced rate of withholding tax, which is wrongly applied mostly.

Unilateral measures cannot prevent other countries from playing the role as flow through country. To avoid international tax avoidance through ‘empty entities’, international agreements are therefore necessary. The committee lastly advises also a constructive attitude by the Netherlands to the ongoing initiatives of the European Commission.

ATAD 1-2

The public perception of tax evasion has shifted in recent years, by taking a drastic turn. In particular, the credit crisis of 2008 has changed the social acceptance of tax avoidance by multinationals in particular. With government deficits and rising government debt, it was considered unfair that a number of multinationals paid (relatively) little tax on their world profits.

This all accumulated into a public hearing of officials of Amazon, Google and Starbucks organized by the Public Accounts Committee in the UK in 2012. The committee chair Ms. Hodge said (the later iconic words):

“We’re not accusing you of being illegal, we’re accusing you of being immoral”.

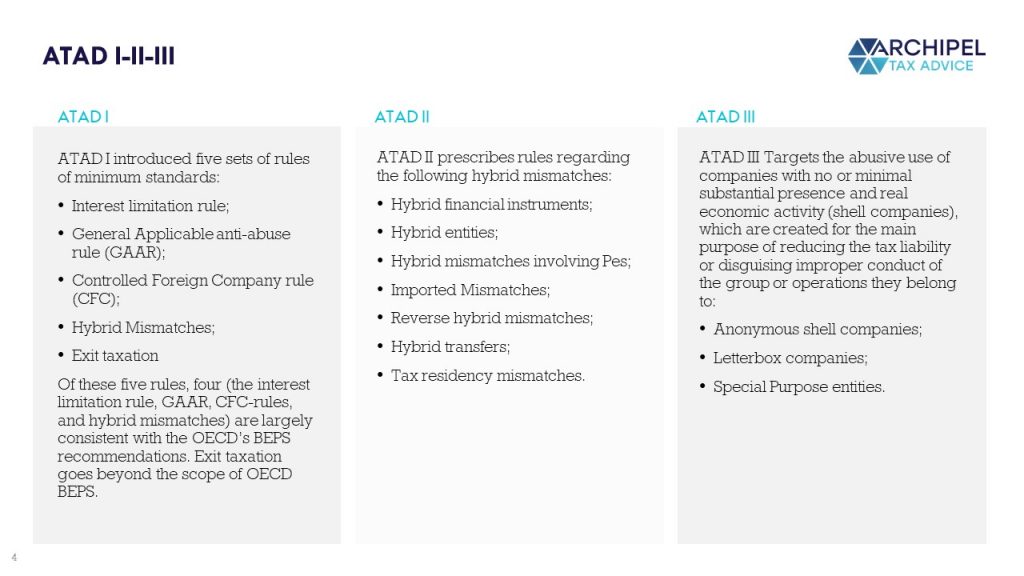

This all led to the BEPS-project and consequently ATAD. There have been 2 Anti-Tax-Avoidance-Directives already put into effect. ATAD 1 introduced 5 sets of minimum standards (interest limitation rule, GAAR, CFC rules, hybrid mismatches and exit taxation). In the second ATAD, subsequent rules relating to hybrid mismatches were finalized on 29 may 2017 when the ECOFIN accepted this directive. ATAD is based on Article 115 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (‘TFEU’).

ATAD 3

Shell Companies

The definition of the widespread term ‘shell’, often interchangeably with terms such as ‘letterbox’, ‘mailbox’, ‘special purpose entity’, special purpose vehicle’ and similar, is defined differently in different contexts. For the purpose of ATAD 3, shell companies refer to three types of shell companies:

- Anonymous shell companies

- Letterbox companies

- Special purpose entities

The main common feature of the above three types is the absence of real economic activity in the Member State of

registration, which usually means that these companies have no (or few) employees, and/or no (or little)

production, and/or no (or little) physical present in the Member State of registration

What will change?

The proposed rules will establish transparency standards around the use of shell entities, so that their abuse can be detected more easily by tax authorities. Using a number of objective indicators related to income, staff and premises, the proposal will help national tax authorities detect entities that exist merely on paper.

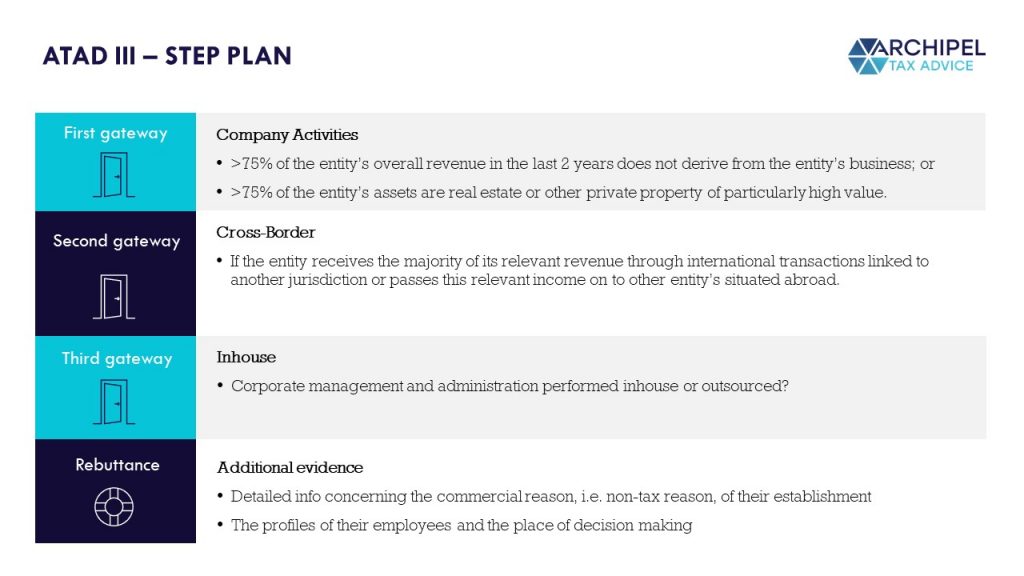

The proposal introduces a filtering system for the entities in scope, which have to comply with a number of indicators. These different levels constitute a type of gateway. This proposal sets out three gateways. If an entity crosses all three gateways, it will be required to annually report more information to the tax authorities through its tax return.

Gateways

First gateway

The first level looks at the activities of the companies based on the income they receive. This gateway is met if >75% of an entity’s overall revenue in the last two tax years does not derive from the entity’s business activity or if more than 75% of its assets are real estate or other private property of particularly high value.

Second gateway

The second level requires a cross-border element. If the entity receives the majority of its relevant revenue through international transactions linked to another jurisdiction or passes this relevant income on to other entity’s situated abroad, the entity passed to the next and last gateway.

Third gateway

The third, and last, level focuses on whether corporate management and administration services are performed in-house or are outsourced.

Crossed all gateways?

An entity crossing all levels will be obliged to report information in its tax return related to the premises of the entity, its bank accounts, the tax residency of its directors and employees etc. These are the so-called substance requirements. All declarations should be accompanied by supporting evidence. If one of the substance requirements isn’t met, the entity will be presumed to be a ‘shell company’.

When will the proposal come into force?

Once adopted by the Member States, the Directive should come into effect on 1 January 2024.

Rebuttal arrangement?

If the substance criteria are not met, entities still have the opportunity to rebut the presumption of being a shell. Additional evidence needs to be presented, such as detailed information about the commercial, non-tax reason of their establishment, the profiles of their employees and the fact that decision-making takes place in the Member State of their tax residence.

Tax Consequences

If an entity is deemed to be a shell company, the benefits and reliefs of the tax treaty network of its Member state are not applicable. Furthermore, the company will not be able to qualify for the treatment under the Parent-Subsidiary and Interest and Royalty Directives. To support the implementation of these consequences, the Member State of residence of the company will either deny the shell company a tax residence certificate or the certificate will specify that the company is a shell.

Furthermore, payments to third countries will not be treated as flowing through the shell entity, and will be subject to withholding tax at the level of the entity that paid to the shell. According with this, inbound payments will be taxed in the state of the shell’s shareholder. Relevant consequences will apply to shell companies owning real estate assets for the private us of wealthy individuals and which as a result have no income flows. Such real estate assets will be taxed by the state in which the asset is located as if it were owned directly by the individual.

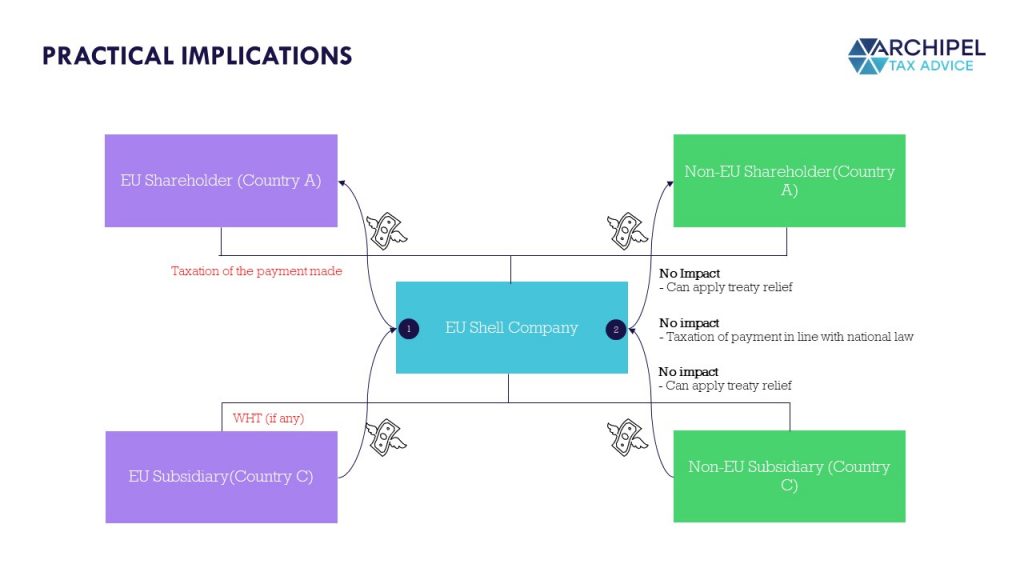

Scenario 1 EU source jurisdiction of the payer – EU shell jurisdiction – EU shareholder jurisdiction

In this case, all three jurisdictions fall in the scope of the Directive and are consequently bound by ATAD3:

- EU subsidiary: this entity will not have a right to tax the payment, but may apply domestic tax on the outbound payment to the extent it cannot identify whether the undertaking’s shareholder is in the EU.

- EU shell: this entity will continue to be a resident for tax purposes in the respective Member State and will have to fulfil relevant obligations as per national law, including by reporting the payment received; it may be able to provide evidence of the tax applied on the payment.

- EU shareholder: this entity will include the payment received by the shell undertaking in its taxable income, as per the national law and may be able to claim relief for any tax paid at the source, including by virtue of EU directives. It will also take into account and deduct any tax paid by the shell.

Scenario 2 Non-EU source jurisdiction of the payer – EU shell jurisdiction – Non-EU shareholder jurisdiction

- Third country subsidiary: may apply domestic tax on the outbound payment or can decide to apply tax according to the tax treaty in effect with the third jurisdiction of the shareholder if it wishes to look through the EU shell entity as well.

- EU shell: will continue to be a resident for tax purposes in a Member State and fulfil relevant obligations as per national law, including by reporting the payment received; it may be able to provide evidence of the tax applied on the payment.

- Third country shareholder: while the third country shareholder jurisdiction is not compelled to apply any consequences, it may consider applying a treaty in force with the source jurisdiction in order to provide relief.

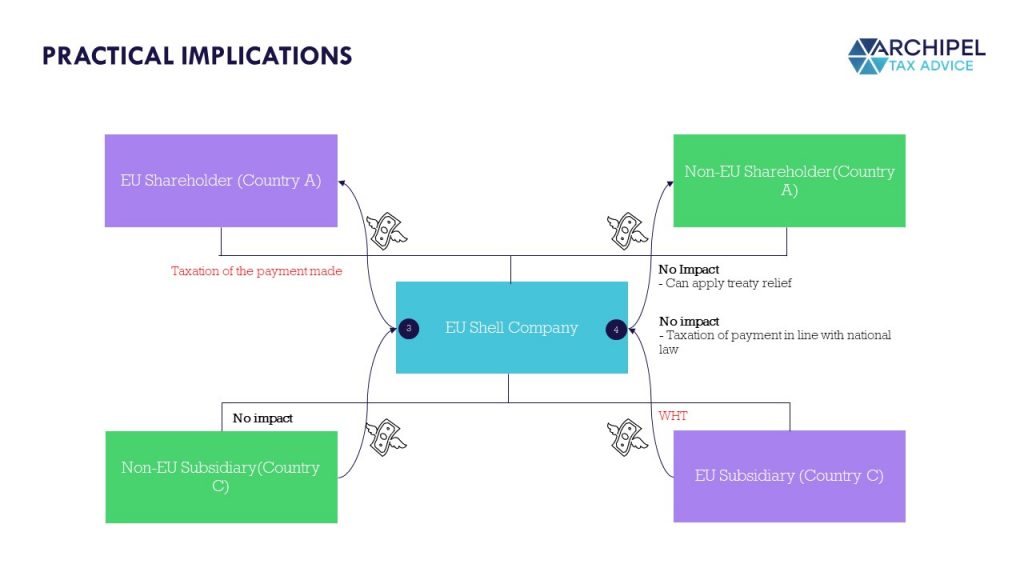

Scenario 3 Non-EU source jurisdiction of the payer – EU shell jurisdiction – EU-shareholder jurisdiction

In this case the source jurisdiction is not bound by ATAD 3, while the jurisdictions of the shell and the shareholder fall in scope.

- Third country source jurisdiction: this entity may apply domestic tax on the outbound payment or may decide to apply the treaty in effect with the EU shareholder jurisdiction.

- EU shell: this entity will continue to be resident for tax purposes in the respective Member State and will have to fulfil relevant obligations as per national law, including by reporting the payment received; it may be able to provide evidence of the tax applied on the payment.

- EU shareholder: this entity shall include the payment received by the shell undertaking in its taxable income, as per the national law and may be able to claim relief for any tax paid at source, in accordance with the applicable treaty with third country source jurisdiction. It will also take into account and deduct any tax paid by the shell.

Scenario 4 EU source jurisdiction of the payer – EU shell jurisdiction – third country shareholder jurisdiction

In this case only the source and the shell jurisdiction are bound by ATAD3 while the shareholder jurisdiction is not.

- EU subsidiary: this entity will tax the outbound payment according to the treaty in effect with the third country jurisdiction of the shareholder or in the absence of such a treaty in accordance with its national law.

- EU shell: will continue to be resident for tax purposes in a Member State and will have to fulfil relevant obligations as per national law, including by reporting the payment received; it may be able to provide evidence of the tax applied on the payment.

- Third country shareholder: while the third country jurisdiction of the shareholder is not compelled to apply any consequences, it may be asked to apply a tax treaty in force with the source Member State in order to provide relief.

Scenarios where shell entity’s are resident outside the EU fall outside the scope of ATAD3.

What to do?

First of all, monitoring the developments in the BEPS 2.0 and ATAD 3 proposals is advised. Also, looking at whether there are operating entities withing the group in low tax jurisdictions, entities with primarily passive income, and companies where the local substance may fall short on the types of criteria suggested by the EC. When the key risks are identified, choices may include removing problematic holding companies, using different jurisdictions, or taking steps to bolster local substance. International groups should take the appropriate measures in time to get ahead of these changes.

Do you have questions regarding the implications of ATAD 3 for your company or do you need certainty in advance? Feel free to call us, or make an appointment with me down below. This is really dynamic work, which also gives you insight into your compliance with the changing international rules. We are happy to help.